By Opal Skinnider

On June 24, 2022, the US Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution does not protect a woman’s right to get an abortion, and that the federal government cannot interfere with individual states’ rights to regulate and criminalize abortion healthcare.

Two months later, Amber Thurman, a 28-year-old Black woman living in Georgia, lay shivering with fever in a hospital bed, wondering what would happen to her six-year-old son, as infection took over her body and her organs failed. Since Georgia had banned abortion after six weeks of pregnancy, Thurman had traveled to North Carolina to take abortion pills, and suffered a rare complication where the pills did not expel all the fetal tissue, which festered in her uterus and quickly spread infection into her bloodstream, causing a life-threatening condition known as sepsis. Her doctors could easily have immediately operated to remove the remaining fetal tissue and stop the sepsis in its path with antibiotics. But they were afraid that operating would violate Georgia’s abortion ban, so they let Thurman suffer for twenty hours, trying treatments that they knew would not help, before operating. By then it was too late, and Thurman died.1

The Supreme Court’s 2022 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization overturned the 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade, where the Supreme Court formally ended the criminalization of abortion by making abortion a matter of personal privacy guaranteed by the Ninth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution. However, Roe was never codified into law by Congress, and the legal right of women in the US to choose whether or not to continue a pregnancy has stood on shaky ground since 1973. Roe was vulnerable to being overturned if and when new Supreme Court Justices, with anti-abortion politics, were appointed by whatever rancid patriarch happens to hold the presidency. Many states with right-wing politics in positions of power resisted Roe by enacting harsh restrictions on abortion care that amounted to defacto criminalization, and by bringing lawsuits against abortion providers, resulting in uneven access to abortion well before 2022.

Consequently, for the 49 years between Roe and Dobbs, abortion was a site of fierce struggle on every level of political life in the US. The Democratic and Republican Parties used abortion as a hot-button issue to sway voters, with women’s’ lives as pawns in their bourgeois power games; high school and college students debated the right to abortion and the “personhood” of the fetus/unborn baby in their classrooms; the Christian Right indoctrinated whole generations of teenagers in revanchist anti-abortion fanaticism; young women from different class backgrounds were brought into feminist politics and/or volunteered to defend abortion patients from the rabid crowds of anti-abortion activists that mobilized to surround abortion clinics; abortion doctors and clinic workers were threatened, attacked, and even murdered.

Many of us who became adults in the period between Roe and Dobbs, and certainly older women who remember the pre-Roe era, recall exactly where we were when we heard that Roe had been overturned. My heavily pregnant coworker read the headline to me off her phone and said in a shocked and almost robotic voice, “So many women will die because of this.” Big bourgeois feminist NGOs and social media Leftists put out the call that there was a big protest downtown, so I went with some comrades. I thought that surely this was an outrage that would bring people into the streets and overtake the opportunists trying to take ownership of the protest, or that we could at least connect with other fired-up women. Maybe this terrible day would shock us all enough to help re-ignite the spark of pro-choice militancy that had flickered but kept burning through the 1990s and early-to-mid 2000s, and seemed to have faded in more recent years. Instead, what we encountered was more like a parade for postmodernist petty-bourgeois feminists who looked forward to posting about their “resistance” on Instagram.

I know that there were many women who were deeply angry and scared on that day who were so removed from political struggle that going to a protest didn’t seem relevant to them (my coworker declined to go with me because she didn’t think it would be worth her time). I think there are many more who have been, and would later be, personally affected by abortion restrictions and bans, but were not even aware of the Dobbs decision on that day because no political leadership has reached them that genuinely speaks to the conditions of their lives and seeks to cultivate their potential political power. And for those of us who are ready to fight back, the “regime of preventive counterrevolution” is really good at channeling our seriousness into “mutual aid” work or into healthcare and nonprofit professions—sometimes very meaningful and necessary work that nevertheless cannot take the place of political resistance. It helps people survive, but accepts bourgeois rule as the last word, and never attempts to bring forth the masses of women into the fight for our own liberation.

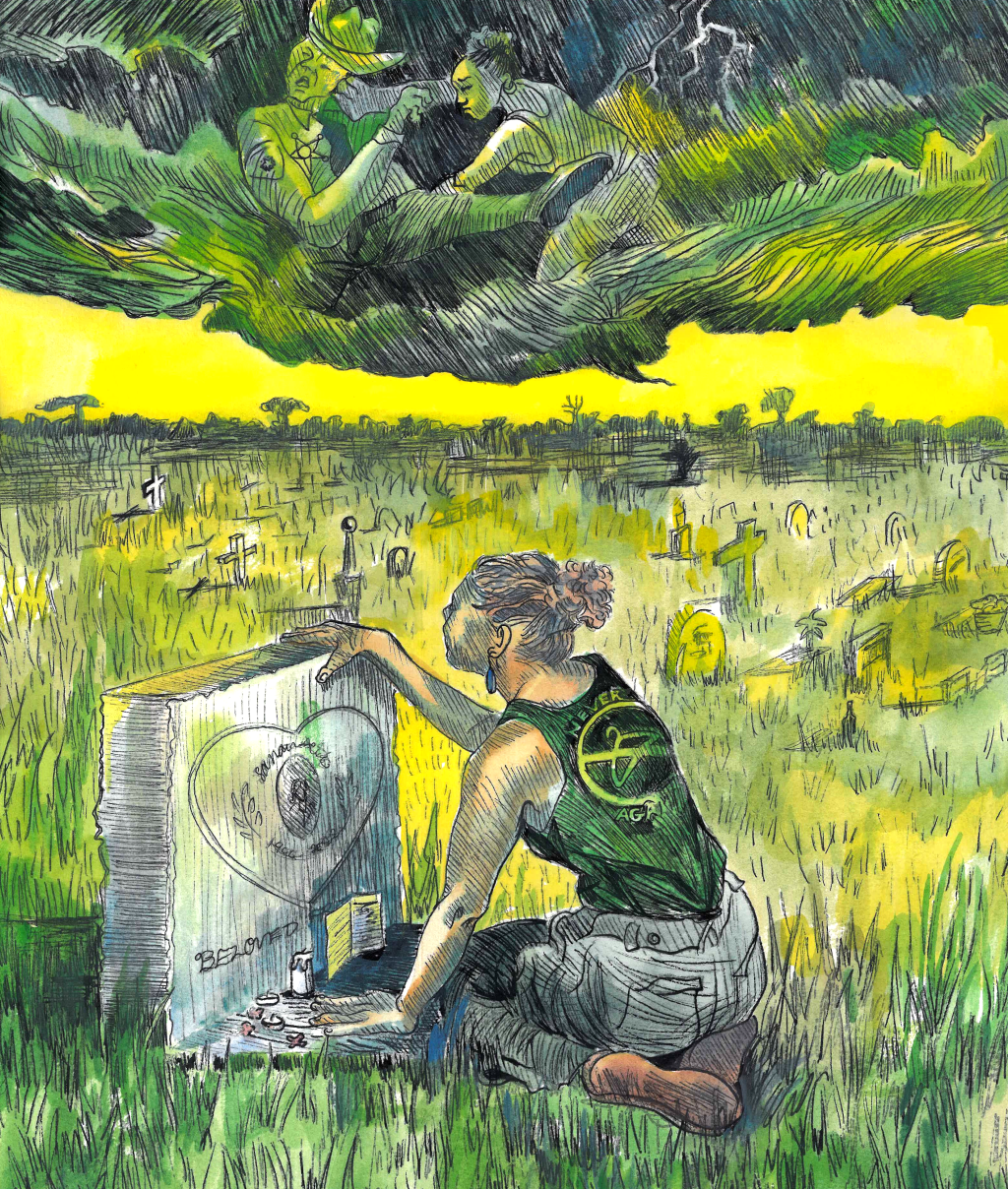

Put simply, the right to an abortion is not the be-all and end-all of women’s liberation, but it is a strong indicator of the status of women in society and our ability to participate in public life. The right to get an abortion is the canary in the coal mine of patriarchy, and as of Dobbs, the canary is dead. By taking away federal protections for abortion, the highest court in this country has basically decreed that women are incubators first, and human beings second. The last three years have seen Amber Thurman and many other women die with lifesaving medical intervention hovering just steps away, because as pregnant women they were not full human beings in the eyes of the state. Where is the righteous fury of women, and why hasn’t it taken shape in a mass movement to make abortion legal? Are we really going to accept that our bodies and serious life decisions are not our own?

How did we get here?

Prior to the mid-nineteenth century, abortion, like most aspects of women’s reproductive healthcare, was unregulated and mostly handled by midwives and other women practitioners outside of the established medical profession, such as herbalists. General consensus in the Western world, backed up by the Roman Catholic Church, was that abortion was a dirty women’s problem like so many other essential parts of life, to be allowed but relegated to the shadows, and that it only became morally questionable with regard to the humanity of the potential baby late in pregnancy. Upon its formation in 1847, the American Medical Association (AMA) first sought to criminalize abortion, not out of concern for fetuses, but in order to take control of women’s healthcare out of the hands of female practitioners. The AMA’s anti-abortion campaign dovetailed with new forms of patriarchal oppression being imposed on women via industrialization and with the rise of capitalism, and criminalization of abortion providers spread across the US.

After the Civil War, the Reconstruction era from 1865–1877 saw Union troops occupying formerly Confederate states in the South to enforce the abolition of slavery and basic democratic rights for Black people. The (temporarily, until Union troops withdrew in 1877 and white supremacist politics took over again) improved position of Black people in the Southern social order, combined with an influx of immigrants in the North, triggered a white supremacist panic. By the end of the nineteenth century, abortion bans were marketed to the reactionary white masses as a way to keep the white birth rate high.

In the century that followed, women who needed abortions often resorted to dangerous DIY methods like inserting sharp objects through their own cervixes to cause a miscarriage, or sought out practitioners working in secret, with or without legitimate medical training. Wealthier white women could sometimes find a real physician willing to practice abortion, but urban emergency rooms were packed with poor, Black, and immigrant women bleeding out with punctured organs or dying of infection. Although exact numbers of abortion-related deaths from this period are hard to come by, some records from the early twentieth century suggest that they accounted for one out of five of all maternal deaths.2

Throughout the early-to-mid twentieth century, abortion legalization carried heavy social stigma but gradually gained traction among progressive activists of various political ideologies. In the early twentieth century, birth control and abortion advocates sometimes came from a women’s liberation-based perspective, or sometimes from the “population control” and eugenics movements, with Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood, exemplifying a combination of the best and worst lines on family planning at the time. She passionately believed that the elevation of women out of their second-class-citizen status rested on legal access to birth control, and also shamelessly pandered to white supremacist, eugenicist ideology to get broad support for her project. Black women who ended up in the hospital to give birth or for unrelated surgery were frequently sterilized against their will, as were Indigenous and disabled people. When the birth control pill was first developed, it was tested on Puerto Rican women without their knowledge or consent.3 But when the radical movements of the 1960s and 1970s began to sweep the US, a powerful renewed feminist movement, often referred to as the “second wave” of feminism, raised the right to safe and legal abortion to the top of their demands and to the forefront of public debate.

The militancy and mass character of the feminist movement of the 1970s came from women who had been drawn into political life through their involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, the movement against the war in Vietnam, and national liberation movements, particularly for Black and Puerto Rican liberation and self-determination. 1970s feminists realized that much of women’s oppression happens behind closed doors, and that mobilizing the masses of women would require bringing women more fully into public life. To radicalize women by exposing the political nature of their personal oppression, feminists organized “consciousness-raising groups,” where small groups of women from different walks of life would meet in private to talk openly about the conditions of their lives and struggle over how to understand and politicize them.4 They brought stigmatized aspects of women’s oppression, especially abortion and sexual violence, out of the shadows through personal health education campaigns and creative exposure. For example, the widely read classic book Our Bodies, Ourselves, published in 1970, was part women’s health manual and part political manifesto, and included excerpts from forthright interviews with ordinary women about their reproductive and sexual health. The short documentary Abortion and Women’s Rights 1970followed two women seeking illegal abortions, and exposed the fact that most women dying from back-alley abortions were Black.5

Underground support networks like the Jane Collective in Chicago helped women access safer abortions from sympathetic medical professionals, and even learned how to perform surgical abortions themselves (notably, the Jane Collective never lost a patient). Seven members of the Jane Collective were arrested in a police raid in 1972 and each was hit with criminal charges carrying a maximum sentence of 110 years in prison, though all charges were dropped when Roe v. Wade was decided in January 1973.6

On August 26, 1970, fifty years after the Nineteenth Amendment had granted US women the right to vote, fifty thousand people took to the streets in New York City for the Women’s Strike for Equality. The protest was called by the feminist organization National Organization for Women (NOW), headed by early second-wave feminist leader Betty Friedan, and focused on the oppression of (mostly white) petty-bourgeois women. However, the masses of women who showed up represented a wide range of political trends stemming from radical movements, far surpassing the bourgeois-democratic limits of NOW. Despite significant political differences between organizers, they agreed that the protest’s number one demand was free, safe, and legal abortion, in every state (with the more revolutionary groups adding an accompanying demand to end the forced sterilization of Black, Puerto Rican, and disabled women).7

The New York Times‘ coverage of the protest illustrates the mass character of the marchers: “Every kind of woman you ever see in New York was there. Limping octogenarians, braless teenagers, Black Panther women, telephone operators, waitresses, Westchester matrons, fashion models, Puerto Rican factory workers, nurses in uniform, young mothers carrying babies on their backs.” Though NOW had secured a parade permit, the marchers refused to comply with the police’s orders to stay in one lane of traffic, and took over the streets. Actions took place in ninety other cities that day, including protests in Boston and San Francisco that drew thousands of people. Women staged sit-ins in men’s restrooms and “baby-ins” in their workplaces, threw eggs at misogynistic radio hosts, and performed guerrilla street theater about abortion. Black women and lesbians, two groups Friedan had been dismissive and hostile toward, defiantly raised the conditions of their oppression, confronted NOW leaders, and challenged straight white feminists to join them, pushing the militant edge of the protest forward.8

The high tide of the women’s movement in the early 1970s coincided with the beginning of deindustrialization, where big employers started to move manufacturing operations outside the US to countries that were economically subjugated by US imperialism, which made labor costs much cheaper. The social structure of the well-paid working class, which was based on nuclear families where the husband/father brought home a decent paycheck from his manufacturing job and the wife/mother did all the reproductive labor (chores, bearing and raising children) and was completely economically dependent on the husband, was profoundly destabilized by both deindustrialization and the radical movements of the 1960s and 70s. Petty-bourgeois women were entering the workforce and the universities in higher numbers than ever before. Proletarian women increasingly became the breadwinners for their families as manufacturing jobs for men dried up. For many in the bourgeoisie, the criminalization of abortion, as a way to enforce the rigid family structures that supported their labor and production needs, seemed less essential to their vision of the future. Some politicians in the Democratic Party started to be open to the idea of decriminalizing abortion.9

Under the influence of a powerful mass movement of women, aided by growing awareness of fatal birth defects caused by the drug Thalidomide (prescribed widely to pregnant women to help with morning sickness), mass public opinion turned in favor of legal abortion. The rise of abortion rights lobbying groups like NARAL (National Alliance to Repeal Abortion Laws, now called Reproductive Freedom for All) and NOW, which had strong ties and allegiance to the Democratic Party, had funding and political support from the liberal bourgeoisie. Sarah Weddington and Linda Coffee, two lawyers who came from the feminist movement and had ties to the abortion rights lobby, searched the country for a woman willing to let them use her case in a legal crusade. They found Norma McCorvey, a Texas woman who needed an abortion, and took her case to the Supreme Court under the alias Jane Roe to protect McCorvey’s privacy. The Roe decision, handed down on January 22, 1973, was not benevolence granted by an enlightened bourgeois court, but rather the culmination of unrelenting feminist militancy and political struggle waged on many fronts.10

From contested victory to capitulationist defeat

Almost immediately after the decision was announced, the backlash to Roe kick-started an anti-abortion movement that would unfortunately also be waged with unrelenting reactionary militancy, on legal, ideological, and terroristic fronts. For the white reactionary masses who already felt their social and political supremacy threatened by the radical movements of the Sixties, the legal enshrinement of a woman’s right to choose whether or not to have a baby brought all those fears straight into their homes, threatening their patriarchal, white, Christian way of life on the most personal basis possible. How were fathers and husbands supposed to exercise patriarchal authority if their wives and daughters could exercise control over their own bodies and reproduction? The longstanding influence of reactionary Christianity on US culture meant that religious leaders were primed to step onto the political stage as defenders of patriarchal right, with many members of the bourgeoisie backing them up with funding and political support.

Rapid legal challenges resulted in revisions to Roe, most importantly the Hyde Amendment of 1977, which banned the use of federal funds, i.e., Medicaid, to pay for abortion care, so that once again bourgeois and petty-bourgeois women could access abortion far more easily than proletarians. Subsequent court cases, usually over struggles between states attempting to restrict abortion and women’s health clinics like Planned Parenthood, chipped away at the ability of healthcare professionals to offer abortion services. For decades before the Dobbs decision, even while Roe still formally protected the right to get an abortion at the federal level, women in states where right-wing politics dominate, particularly in the South and rural areas, have contended with “waiting periods” (going to an initial consult, then having to wait a day or more for your abortion to give you time to change your mind), mandatory “counseling” sessions where they are forced to view ultrasound imagery of their fetus, and driving for hours and even to different states just to find an abortion provider since so many have been forced to close down.11 Immediately after Roe, in 1973, the US exported anti-abortion politics via the Helms Amendment, which prohibits foreign aid funds from being given to any organization that provides abortions, effectively blackmailing poor countries and using reproductive healthcare as a tool of imperialism.12 In 1980, Ronald Reagan won the presidential election in part by mobilizing Christian fundamentalists through promising to be the first explicitly anti-abortion president.

Since the Roe decision, public opinion surveys conducted by different electoral pollsters and researchers consistently show that most people in the US think abortion should be legal, at least early in pregnancy.13 Certainly, women of all demographics and political views get abortions—abortion clinic workers will tell you about patients who they recognized from the picket line outside the clinic. Anti-abortion activists make up a fairly small percentage of the US population, but they have an outsized effect on public perception of abortion and on people’s willingness to talk openly about abortion and take action to support legality. Their aggressive promotion of anti-abortion politics has come up against the narrowness of the pro-choice establishment that has increasingly dominated the pro-choice movement since Roe. The pro-choice movement, without a radical ideological backbone, has been reduced to a constant defensive posture in the face of the anti-abortion movement’s strong reactionary ideological backbone. This has allowed the anti-abortion movement to control the struggle, resulting in two very ardent sides of a national, public debate around fetal viability or personhood, while in actuality most people in the US support legal abortion, and the debate is really around whether women can have control over our own bodies and lives.

Initially, anti-abortion activists were in lockstep concerning their supposed concern for the rights of “the unborn child” as a veil over their interest in oppressing women. The modern anti-abortion movement has its origins in small Catholic protest groups that organized during the 1960s to oppose the growing movement for abortion access, and the National Right to Life Committee organized by Catholic bishops, which developed the initial religious arguments surrounding the “sanctity of human life” and the accompanying idea that “life begins at conception.” The burgeoning anti-abortion movement found spokespeople in former abortion providers who were willing to claim that abortion caused real pain to fetuses. In 1972, the Wilkes, a Catholic anti-abortion doctor-and-nurse couple, published a book of graphic images of aborted fetal remains. In 1984, an anti-abortion doctor made a film called The Silent Scream, which used ultrasound imaging to document a twelve-week abortion in progress, using special effects and photos of a pregnancy at nearly full term to create the impression of a nearly fully formed baby thrashing around in pain. These types of images became the anti’s go-to visual propaganda for the next several decades.14

In her 2025 book From the Clinics to the Capitol: How Opposing Abortion Became Insurrectionary,Carol Mason points out that by creating a mythically personified fetus, the anti-abortion movement created a symbol of victimhood that could make the white reactionary population’s sense of their own victimhood at the hands of Roe visible and concrete—which was very necessary since, of course, their victimhood is not real. The personified fetus image was central to a propaganda campaign that won over people beyond its white reactionary base, becoming ubiquitous on billboards, bumper stickers, pins, T-shirts, and giant screens mounted on trucks and driven through college campuses.15

As fundamentalist Protestants joined Catholic anti-abortion activists in their own united front against women’s liberation, the personified fetus spread throughout the country and an entire generation of (mostly) white children growing up in Christian youth groups were told to see themselves as “survivors of the American Holocaust” and to identify themselves with the threatened fetuses. The indoctrination of young people has included “haunted houses” where teenagers are confronted with gory tableaus of helpless women being ripped open by evil abortionists, trips to Washington, DC for the annual March for Life where they build social ties with other anti-abortion activists, and regular protests outside abortion clinics where they are taught how to harass and threaten patients trying to get to their appointments. Thus in the 1980s and 90s, the anti-abortion movement trained a very widespread and passionate grassroots base.16

The anti-abortion movement is overwhelmingly white, and has deep connections with white supremacist political life ever since its origins in fears of a declining white birthrate and greater freedom for white women threatening patriarchal bourgeois hegemony in the early twentieth century. However, this essential characteristic has been obscured by the inclusion of some Black and Latino religious people in the movement. Anti-abortion activists use the very real and horrifying history of forced sterilization of Black women, and the fact that Black women make up a higher percentage of abortion patients compared to white women, to argue that legal abortion is tantamount to Black genocide. The anti-abortion movement also appropriates the history of real resistance against genocide and oppression to lend themselves the flavor of righteous resistance: Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X quotes next to photos of white babies with their fists raised; comparisons to slavery (with themselves as the “abolitionists”) and the Holocaust.17 Meanwhile, the anti-abortion movement has functioned very effectively as a Trojan horse for white nationalism, with the most widely accepted layer of teenage activists and prayer groups paving the way for openly white supremacist politics that explicitly tie legal abortion to their fears of being “replaced” by Black people and immigrants.

Throughout the 1980s and 90s, anti-abortion activists became more and more militant as their fight on legal and judicial fronts succeeded in making it harder and harder to get an abortion. Operation Rescue (OR), the best-known of the more radical anti-abortion groups, rejected the path of legislative reform to achieve their goals in favor of direct action, blockading abortion clinics with their bodies and sometimes getting inside clinics to destroy equipment. Their actions involved thousands of participants and would not only make it impossible for patients to access the clinic on the day of the “rescue,” but also shut down traffic, fill up the local jail, and garner widespread media attention.18

The more militant end of the anti-abortion movement had significant overlap with the rise of anti-government, white supremacist movements in the 1980s and 90s. Some of the most violent anti-abortion activists/terrorists, like clinic bomber Eric Rudolph or followers of the shooter handbook, The Army of God Manual, came from this crossover group, and attended the same religious rallies and gun shows. They participated in mainstream, legal anti-abortion groups like OR, distributing literature like The Defensive Action Statement, which argued Christian Nationalist theological justifications for murdering abortion doctors.19 Rudolph, who came from the same neo-Nazi ideological background and social milieu as Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh, bombed the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta as a statement against (what he saw as) US collaboration with other, non-white and non-Christian countries, before also bombing two women’s health clinics and a lesbian nightclub.20

Throughout the 1990s, the anti-abortion movement published lists of abortion doctors and their personal information online to dox them, making it easy for the most violent wing of their movement to find people to intimidate and murder. This had the intended chilling effect on abortion providers, especially those working in states dominated by right-wing politics and in isolated rural areas, and many shut down their practices. Doctors who decided to take a stand for women and keep practicing were faced with having to hire armed security details and wear bullet-proof vests.21 The 1980s and 90s saw 153 assaults, 383 death threats, three kidnappings, eighteen attempted murders, and nine murders of abortion providers.22 Victims included the heroically intrepid and tireless women’s health advocate Doctor George Tiller, who survived his clinic being firebombed in 1986, and being shot in 1993, before finally being murdered during Sunday morning service at his church in 2009.

In the 2010s, the anti-abortion movement subtly changed its tone, and began to focus less on fetal personhood and more on women as the real victims of evil abortion providers. The bloody fetus billboards went away, to be (mostly) replaced by stock photos of sad-looking women with captions that say things like “I regret my abortion―Lisa, age 22” or ultrasound images with word bubbles that say “Mommy, I already have fingernails!” I’ve even seen a bumper sticker that says “Feminism begins in the womb.” Newer right-wing groups like Abolish Human Abortion make a point of being “pro-woman” and to emphasize the real or imagined negative aspects of going through with an abortion. Catholic churches started to hold a special Mass not just for the “souls of the unborn,” but also for the healing of women who have had abortions. “Crisis pregnancy centers,” which often pose as abortion clinics, had sprang up over previous decades and further proliferated. They effectively trapped pregnant women, sometimes for hours, and subjected them to anti-abortion propaganda, offered adoption counseling and baby supplies, and also misdirected their “clients” with this malicious charity until the window for them to obtain an abortion closes. Using a diversity of tactics, the anti-abortion movement rebranded itself as the true women’s rights and health advocate right at the moment when militant feminism was seriously in a slump.

Where was the women’s movement this whole time? There was certainly a militant wave of resistance to the anti-abortion movement in the 1980s and 90s. Some young women coming of age after Roe were outraged by the incremental successes of the anti-abortion movement in restricting our reproductive freedom, whether we were being raised in a Christian fundamentalist worldview only to realize it was all decrepit bullshit, or whether we had older mentors to illuminate the arc of history to us and explain what we would lose if the anti-abortion movement won. Pro-choice militancy during this period principally took the form of clinic defense, where pro-choice activists put their bodies on the line to defend abortion clinics and their patients from rabid Operation Rescue activists. This often meant confronting the police and demanding that cops quit protecting OR activists who were blocking clinic doors and start arresting them. Clinic defense groups like Bay Area Coalition Against Operation Rescue (later Bay Area Coalition for Our Reproductive Rights, or BACORR) also took creative forms of protest right to the doors of OR-affiliated churches. They used satirical street theater, notably a 1989 “wedding scene” where a woman dressed in a bloodstained-looking wedding dress was beaten by the “wedding guests” with coat hangers and plastic baby dolls. They even got inside OR rallies to set off stink bombs.23

In 1992, huge protests erupted all over the country as the Supreme Court deliberated on whether to overturn Roe in Planned Parenthood v. Casey. Roe was upheld by the slimmest of margins, a 5-4 vote. Kathryn Kolbert, the lawyer who argued on behalf of Planned Parenthood, later said that Roe was not overturned in 1992 only because the militancy of the mass protests convinced the Justices that the legitimacy of the Court would be called into question if they did not bend to the will of the enraged women outside.24

The militant end of pro-choice activism in the 1980s and 90s was driven not only by rebellious young women, but also by the presence of a previous generation of women who came up through the 1970s feminist movement, LGBTQ activists from AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), the fighting spirit of many anarchist feminists, and the leadership of the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP). Besides clinic defense, pro-choice activists of this era also organized abortion funds and support networks to help women in states with little abortion access travel to get the healthcare they need, vigorously debated and confronted anti-abortion activists wherever they raised their little heads, and made powerful art that engaged with the realities of women’s oppression and propagandized for abortion access. The music of rebellious woman artists, from Ani DiFranco to Queen Latifah, shaped the political consciousness of a generation of women and gave us a women’s empowerment soundtrack.

Even as the 1980s and 90s generation of pro-choice activists recognized the precariousness of Roe and rose to the challenge of defending abortion access as a crucial piece of the women’s liberation struggle, abortion rights nonprofits and lobbying organizations aligned with the Democratic Party had all the funding and massive partisanship throughout the US compared with more radical groups such as Refuse & Resist. The impressive gains of the 1970s feminist movement primarily benefited petty-bourgeois women, giving them greater access to higher education and white-collar work and improved bourgeois-democratic rights. This section of women who benefited the most, and felt most partisan to the Democratic Party, took control of the pro-choice movement as they moved into positions of power in the 1980s and 90s. They cultivated a social base in the liberal petty-bourgeoisie that viewed abortion as something to defend from within the Democrat establishment, and whose preferred forms of “defending” abortion rights are donating to nonprofits and political candidates and voting Democrat. This “pro-choice establishment” took part in the cultivation of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie starting in the mid-2000s,25 and whittled away at the militancy and rebelliousness of the feminist movement. The postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie first moved discussion of women’s liberation from the streets to the university classrooms and boardrooms, then retreated from acknowledging women’s oppression altogether. With the decline of the RCP in the 2000s, and with it, revolutionary leadership that raises the consciousness of the masses of women, explains how all the pieces of our oppression fit together, and exposes the root causes of capitalism-imperialism, defending Roe has been left to the feminist lobbyists and nonprofit careerists.

Today, the heavy hitters of the pro-choice establishment are really Democratic Party-allied groups like NOW, NARAL, and even Planned Parenthood, which at least actually fights to provide abortion care, but is still beholden to the liberal bourgeoisie. They do not hesitate to pour cold water on clinic defense volunteers who are ready to get in the mix and confront the antis. In some confrontations between Operation Rescue and counter-protesters, they have even sicced the police on the counter-protesters, saying that they, the well-funded nonprofit, are in charge and that they don’t condone such defiance. As one clinic defender put it, writing about how the Feminist Majority Fund had betrayed grassroots activists in California, “While the Fund and other liberal feminist nonprofits ordered clinic defenders to stop protecting clinics and simply hold a ‘Keep Abortion Legal’ sign on the sidelines, the Christian Right supported and honored its grassroots movement… [W]hile the pro-choice establishment dismantled our movement, grassroots activists of the Christian Right have never stopped protesting outside clinics.”26 Even Planned Parenthood’s role is controversial within the abortion care world; one abortion clinic worker explained to me that Planned Parenthood gets the majority of donations from people who want to support abortion access, but they typically don’t care for patients with pregnancies that are further along in gestational age, which are more expensive abortions in terms of surgical equipment, time, and expertise. Independent clinics eat the cost of that type of care.

Meanwhile, the Democratic Party, to which the pro-choice establishment is inherently beholden, could not give less of a fuck whether poor women in rural areas and the South can get abortions or not. Since Roe, top Democrats have consistently sacrificed abortion rights for political expediency, whether that meant cynically paying lip service to abortion rights for votes while doing absolutely nothing to protect them, or opposing abortion access outright. In 1992, Bob Casey Sr., then Pennsylvania’s Democrat governor, challenged Roe in the Supreme Court with Planned Parenthood v. Casey, and nearly succeeded in overturning Roe. The case did succeed in seriously limiting Roe by making it possible for states to impose restrictions on abortion access. Joe Biden’s old Catholic corpse has worked against abortion rights for nearly his entire career.27

Although Roe has always been known to be fragile, Democrat lawmakers have never moved decisively to make abortion protected by its own laws on the federal level, and not just judicial precedent. Signing a bill to codify abortion into federal law was one of the first campaign promises that President Barack Obama broke, even as his Party controlled the House of Representatives and the Senate from 2009–2011. And toward the end of Obama’s second term, it became clear that the next president would be able to appoint new Justices to the Supreme Court. That next president was Donald Trump, who was able to appoint three Justices―a third of the entire bench. Each Trump-appointed Justice deliberately obfuscated their position on Roe in their confirmation hearings, though each had spoken publicly on their anti-abortion stance. Democrat lawmakers accepted this obfuscation and moved forward to confirm Justices who had essentially vowed to overturn Roe once they had the opportunity. And as the Court inexorably inched toward becoming a panel of reactionaries, the Democratic Party still did not act to protect abortion access on the federal level.28

By the time the Supreme Court prepared to hear Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the writing was very much on the wall. Roe was overturned by a vote of 6‒3, and thirteen states—Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, and Wyoming— enacted “trigger laws” to immediately ban or restrict abortion access.29

Where are we now?

I maintain that Democrat politicians never had a happier day than the day the Supreme Court overturned Roe. Struggling to appear relevant and somewhat progressive, they finally had an outrage around which, surely, they would be able to rally their voter base, manipulate the masses of women into thinking that only the Democratic Party could save them, and position themselves as champions of women. After all his feet dragging and outright betrayal, Obama posted a mournful, long-ass Twitter thread about abortion rights. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez headed out to get a photo-op at a march in New York City. JB Pritzker, governor of Illinois with his eye on the presidency, declared Illinois a “safe haven” for reproductive healthcare access, and moved to sign several laws protecting abortion providers and anyone traveling to Illinois for an abortion. Other states with Democrats dominating government leadership quickly enshrined abortion access with similar “shield laws” and through state constitutional amendments, ensuring that politicians could pat themselves on the back and the petty-bourgeoisie in their ivory tower blue states would be able to get whatever reproductive healthcare they need, and not have to worry about women in the South. After all, they can just come to New York/California/Illinois!30

Anti-abortion trigger laws in “red states” caused panic among people who had abortion procedures scheduled. For many in states that had already severely restricted access, patients had been through a torturous process to get to this point, often involving tricky childcare arrangements and time off work, travel and lodging in a different state, raising hundreds of dollars, humiliating mandatory “counseling” appointments, and medically unnecessary, invasive transvaginal ultrasounds. In some states where abortion access had been most hotly contested, it was unclear whether trigger laws had been enacted or not. Andie, an abortion clinic worker in Ohio, told me:

We were rushing to get abortions done that day because we knew they were going to try and put a ban as soon as possible. So we had our doctor going as quickly as possible, while not compromising patient care, to get everybody done. Luckily we finished everybody who was scheduled that day. Later, we got the news they were enacting a six week ban [a ban on abortions performed after six weeks of pregnancy, before most people know they are pregnant]. We had to call a lot of patients and tell them they would have to be seen out of state. So it’s also [the burden of] traveling.

Ohio’s six week ban was successfully squashed, and abortions can be provided until 21 weeks of pregnancy, but many of Andie’s patients don’t know that, and the confusion has kept people from scheduling their abortions in the appropriate time frame. By the time they realize they can get an abortion, and make the complicated arrangements, it’s sometimes after the 21 week cutoff. Andie described being “scarred” by having to turn people away during the time Ohio’s six week ban was in effect.

In Illinois, which is situated to be the easiest “sanctuary state” to travel to from the South, abortion clinics have been overwhelmed with out-of-state patients. Planned Parenthood has had to shut down some locations that provide birth control and other reproductive healthcare but not abortions in order to divert resources to their abortion clinics, notably in predominantly Black neighborhoods in dire need of medical services like Englewood in Chicago.31

Andie and Jan, another clinic worker in Ohio, described an increasingly hostile environment at work, with staff teetering on the edge of burnout. Andie explained how patients who are frustrated with the bureaucratic intake process sometimes call the workers there “baby killers.” As in most workplaces, the executive staff who call the shots has little to do with the reality of the frontline workers; they are beholden to donors and political players more than they are to patients or the workers putting their safety on the line to provide reproductive healthcare. Frontline workers are pressured to never call out sick or take paid time off “for the cause.” I asked Jan if she felt safe at work; she laughed and said, “If anyone feels safe in America right now, congratulations on your millions of dollars,” but acknowledged that her work has felt more dangerous since the Dobbs decision. Andie pointed out that Vance Boelter, the gunman who murdered Minnesota Democrat politician Melissa Hortman and her husband in June 2025, had a background in anti-abortion extremism and a list of other assassination targets in which abortion providers featured prominently. Andie said there’s a security protocol on paper for the clinic, but there’s not really anything between frontline workers and their patients, on the one hand, and a potential active shooter, on the other. Yet, “there’s so much pressure to keep going, just like a rat on a wheel, and I feel strongly that I couldn’t do it if it wasn’t in my values.”

What about people in states where abortion is no longer legal? Revanchists can try, but they can’t actually turn back the clock. Women in the US have had nearly fifty years of abortion access (if uneven). The vast majority of women will no longer bear children just to give them up to strangers; adoption rates have steadily declined since Roe, and that shows no sign of changing. Nor will we go back to the desperate days of coat hangers and knitting needles. Today we have abortion pills and the internet, so for women in states with abortion bans, options look a lot different than pre-Roe.

Medication abortion accounts for 63% of all abortions in the US as of 2023. It is usually a two-day process; first you take mifepristone, which blocks progesterone, causing the death of the fetus, then misoprostol, which causes uterine contractions to expel the fetal tissue. Telehealth has made it possible for patients to order the pills online through various websites and apps, and to manage their abortions at home, usually without complications. Organizations like Plan C mail the pills discreetly in unmarked packaging. Though medication abortion is generally only safe in the first trimester of pregnancy, and can sometimes require a doctor’s care if not all fetal tissue is expelled (as in Amber Thurman’s tragic story), it’s been crucial for women in the 26 states that have now criminalized or severely restricted abortion.32

Of course, these states are aware that people are still getting abortions by ordering pills online, and many have classified the two drugs as controlled substances. As of December 4, 2025, Texas penalizes any provider within the state who provides abortion pills and allows any private citizen to sue anyone who seeks or provides abortion pills, including out-of-state providers, for up to $100,000.33 This is an extension of the state’s “bounty hunter law”: since Dobbs, in Texas, any private citizen can sue anyone seeking or providing an abortion for a minimum reward of $10,000. Friends, partners, and even children of any woman seeking an abortion are encouraged to turn her in.34

Though most abortion pill telehealth providers are operating out of states with shield laws, states with bans have started to find ways to go after them, with Texas and Louisiana issuing warrants for the arrest of telehealth doctors in California and indicting a New York-based provider. One Louisiana case was brought on behalf of a woman who decided to continue her pregnancy, but whose boyfriend falsely used her information to get abortion pills mailed to him, and forced her to take them. He has not been charged with a crime―only the doctor has.35 In March 2025, Maria Margarita Rojas, a Texas midwife who has devoted her life to serving Spanish-speaking proletarian women, was arrested for providing abortions.36

Women traveling out of state to get an abortion have been hunted down by law enforcement, particularly in Texas, where cops have used license plate tracking technology to follow up on tips from bounty hunters.37 Since Dobbs, over 400 pregnancy-related prosecutions have been brought nationwide, not only prosecuting women for seeking abortions, but also using “fetal personhood” laws to bring criminal child endangerment charges against pregnant women for drinking, smoking, or using drugs during their pregnancy, whether or not a child is born with medical problems as a result. Over half these cases have been brought in Alabama, with the vast majority of the rest brought in other states with abortion bans. Women have been arrested for suspected abortion after having a miscarriage, or for “improper disposal of a body” for not reporting the miscarriage as a death to the police.38 This overall criminalization and legal objectification of women in general―pregnant women as well as anyone who can potentially get pregnant―also includes law enforcement surveillance of social media, private text messages, and potentially even menstrual cycle tracking apps. On the latter, as of this writing no criminal case has cited cycle tracking data as evidence, but warnings from the tech industry that people’s personal medical data could be handed over without a warrant, or even sold for profit, have contributed to the very real sense of a lack of privacy and basic dignity for women in abortion ban states.39

As my coworker predicted the day she told me Roe had been overturned, many women have died. The Gender Equity Policy Institute has found that, post-Dobbs, pregnant and postpartum patients are now twice as likely to die in states with abortion bans. Black women, who already have the highest rates of maternal mortality in the US, are more than three times as likely to die during pregnancy and postpartum in those states than white women, and Latina women in Texas are three times as likely to die than Latina women in California. Maternal mortality in Texas overall (which already had the harshest restrictions on abortion pre-Dobbs, and the worst maternal mortality rates) rose by 56% in 2022, the first full year of the state’s abortion ban.40

All state medical boards have review processes for maternal deaths, but since Dobbs, abortion ban states have refused to collect data on maternal deaths in order to obscure their crimes against women. Texas has actually prohibited its maternal mortality review committee from reviewing any deaths that may be related to abortion, which includes some miscarriages, since emergency care related to an incomplete miscarriage is often identical to care related to an incomplete abortion.41 Texas also instructed its committee to not review any maternal deaths at all from 2022 and 2023. Idaho disbanded its maternal mortality review committee entirely. Georgia fired every member of its committee and has yet to replace them. North Dakota has a committee that has never once met to review cases.42

In the vacuum left by these cover-up attempts, the independent news website ProPublica has started an investigative journalism project, “Life of the Mother,” supported by OB/GYNs and other medical experts, that meticulously searches raw data from maternal death reports to learn which deaths were preventable, and where care was withheld due to abortion bans. ProPublica’s journalists have uncovered hundreds of cases since 2022, mostly in Southern states, where pregnant women were denied care and died, specifically because the care they needed was prohibited by the state’s abortion bans. Amber Thurman was the first, but far from the last, woman to die of sepsis because doctors refused to remove septic fetal remains left by either an attempted abortion or a miscarriage. In Texas alone, sepsis rates in hospitalized pregnant women rose by 50% in the year after Texas’ initial abortion ban.43 In 2023, a teenager named Nevaeh Crain died of sepsis-related organ failure during a miscarriage, after three separate emergency rooms refused to treat her.44 Even when sepsis is not fatal, it can result in organ failure and brain damage.

Other women have been denied abortions when their pregnancies threatened their lives, an exception most states with bans supposedly honor. Tierra Walker in Texas asked for an abortion when she developed preeclampsia, a life-threatening condition caused by problems with blood flow in the placenta which can only be resolved by removing the placenta and therefore ending the pregnancy through either delivery or abortion, depending on the gestational age of the fetus. She died after being denied the abortion that would have saved her life.45 More women coming to hospitals for miscarriages end up suffering severe blood loss because doctors are hesitant to end their hemorrhaging by evacuating the uterus.46

In Georgia, where Amber Thurman died and where Black women are three times as likely as white women to die of pregnancy-related complications, Adriana Smith, a thirty-year-old Black nurse, suffered multiple blood clots in her brain while nine weeks pregnant. Doctors declared her brain-dead, but refused to take her off life support to allow her pregnancy to develop. Smith’s family was forced to watch her lifeless body decay for months until her baby was born via emergency C-section. As of this writing, Smith’s son, who was born extremely prematurely, has been in neonatal intensive care for six months.47 If Adriana Smith’s story doesn’t illustrate how women are treated under the law as no more than incubators, and property of the state, under Dobbs-era abortion bans, I don’t know what does. If you’re viewed as someone who might be able to get pregnant, you are surveilled and stalked; if you are pregnant and intend to keep your baby, you are considered guilty until delivered or dead; if you decide to have an abortion, you are to be disciplined and punished.

There is no data on how many women who, given the choice, might have ended their pregnancies, but were forced to give birth because of post-Dobbs laws. We have no way of knowing how many people have stayed in abusive relationships, sunk into deeper poverty, given up their career or education, married someone they otherwise wouldn’t have married, or developed lifelong pregnancy-related health conditions because they couldn’t access an abortion. Jan offered that she does know of cases in which patients who initially wanted an abortion, and were willing to travel to get one, couldn’t get their affairs in order fast enough and simply lost the race against the clock. She also knows of women who made arrangements with their doctors to have their tubes tied after childbirth but only found out, once they became pregnant again, that it never happened. As Jan puts it, we are in an era where “women aren’t seen as players in their own lives… Everything is super fucked, everything is on fire, we’re just going to keep going to work until they tell us we can’t anymore.”

What are we even doing?

Apart from the “shield laws” insulating Democrat-controlled states from anti-abortion prosecution, there has been no meaningful political response from even the pro-choice lobby, let alone anything resembling a mass movement for women’s liberation. Many people think that the politicians are the only people who can really change things; at the same time, most people have no faith in bourgeois politics, and nowhere else to go for political leadership. For the most part, I think the proletarian masses get, if they paid attention at all, that the righteously indignant rhetoric from Democrat politicians after the Dobbs decision was just grandstanding. Politicians and the bourgeoisie they represent have no reason to feel any real sense of urgency over abortion bans; anyone with plenty of money, from the postmodernist to the liberal to the reactionary sections of the bourgeoisie and the upper petty-bourgeoisie, can access whatever medical care they need or want, including abortion, regardless of whether it is legal.

Abortion funds have been a crucial part of making abortion access a reality at all ever since the passage of the Hyde Amendment. These funds are, generally speaking, nonprofits that raise money through donations and administrate payouts to applicants who need help paying for their abortion. They range in size and scope, with some staffed by volunteers and others with a professional staff that also engages in public health education and political lobbying; the latter has significant overlap with the pro-choice establishment.

Post-Dobbs, abortion funds are more important than ever. Frequently, they not only raise money to pay for abortions, but also arrange travel and lodging for patients coming from out-of-state. The Chicago Abortion Fund, for example, now assists patients coming to Chicago for abortions from all over the Midwest and the South.48 Abortion funds attract passionate volunteers who truly believe in making reproductive healthcare available by any means necessary. Funds also have the legal standing and resources to wage important legal battles. The Yellowhammer Fund in Alabama, which helps women travel out-of-state for abortions but shut down operations after Dobbs, recently opened their work back up after winning a lawsuit against the state in March 2025. Not only were they able to resume operations, but they created a legal precedent for blocking the state from prosecuting women traveling for an abortion.49

Riskier and more radical forms of action include the underground networks delivering abortion pills to women in states with bans. Mexican activists from the organization Las Libres (the free ones) who have experience resisting abortion bans in their country that were only repealed in 2021, have helped women in the US buy abortion pills wholesale in Mexico and distribute them anonymously to patients in Texas, particularly to undocumented immigrants.50 In more disparate, word-of-mouth underground work, doulas and midwives in states with shield laws stock up on abortion pills and smuggle them to women in the South. One Black doula from Chicago (using the pseudonym Ashaba) with ties to the South, who makes monthly trips to provide illegal abortion care and supplies in Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana, explained the reasons for the risks she takes in a November 2025 interview with PBS:

Ashaba: I understand that I can go to jail. I understand that everything I have worked for can be taken away.

Interviewer: And why? Why are you willing to make that bet?

Ashaba: Because I have daughters, because I have friends, because I have loved ones that I want to see safe, and I know I cannot wait on a system that does not and has not cared for us.51

Republican politicians describe these heroic activists as drug dealers and quacks, or intentionally mischaracterize them as opportunistic butchers a la the pre-Roe back-alley abortion grifters. For the 62.7 million women and girls living under abortion bans, especially those without the resources to travel, this care represents a literal lifeline. At the same time, this crucial work, without a relevant political movement, also functions as an off-ramp, diverting the dynamic outrage of the best and bravest abortion activists away from actually overturning this noxious patriarchal system. Later in the PBS report that interviewed Ashaba, a Southern underground abortion pill activist describes the ability to get pills in the mail and self-manage an abortion at home as “a real moment for poor folks. It kind of puts the power in their hands.”

With huge respect to the work this courageous activist does, no, it does not put power in their hands, even as it ameliorates their suffering. It is a form of “Pac-Man politics,” where revolution as the answer to oppression is replaced with mutual aid or engagement with electoral politics, the idea being that bourgeois rule must be chipped away at bit by bit rather than overthrown.52 When the most dedicated activists in the pro-choice movement accept the bourgeois state decreeing that abortion is illegal, and try to find ways to go around the state rather than challenging the bourgeois state itself in order to put state power in the hands of the proletariat, “mutual aid” work becomes an avenue of capitulation rather than resistance. I would argue that the allure of mutual aid efforts, which really do seem much more meaningful and concrete when revolution has vanished in most people’s consciousness as a real possibility, are drawing people’s time, energy, and resources away from mobilizing the masses of women for their own liberation.

Before virtually every pro-choice organization and activist had the chance to insist on capitulation to Dobbs, there was a wave of militant protests in 2022 that attempted to harness the outrage of young women and foment political resistance to abortion bans. The most serious attempt was spearheaded by the Revolutionary Communist Party which, despite having stagnated and deteriorated into dogmatic irrelevancy over the last couple decades, did the correct thing in pulling together more confrontational protests and giving fired-up young people something better to do than join parades. At the RCP’s initiative, Rise Up 4 Abortion Rights (RU4AR) was formed in early 2022 by people who were at least wise to the increasingly serious existential threats to Roe. RU4AR organized protests in large metropolitan cities across the US, including one that took the fight right to Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s home, and used high school walkouts to pull teenagers into political life. Decked out in green bandanas inspired by the colors of Latin America’s Green Wave movement for reproductive rights, RU4AR staged theatrical protests with often shocking visuals to grab people’s attention and expose the brutal nature of abortion bans. Protesters wore white pants with the crotch splashed with blood-red paint to dramatize the deathly consequences of abortion bans; a small group of women stripped down to their underwear during Christian nationalist Joel Olsteen’s megachurch service; a fifteen-year-old girl with several other teenagers marched around Amy Coney Barrett’s house holding baby dolls, with their hands bound, wearing bloody-looking clothing.53

After Dobbs, as the righteously angry among us looked for a way to really fight back and joined protests organized by RU4AR, representatives of pro-choice lobbyists and nonprofits, as well as Leftist organizations and social media influencers, slammed RU4AR for daring to deviate from postmodernist identity politics. Democrat-aligned groups did not want protests to go beyond parades (in many cases, really electoral rallies for their politicians), and mustered 23 of their activist organizations to sign an open letter denouncing RU4AR in July 2022.54

Social media leftists were all too eager to pile on in the weeks that followed. On Reddit and Twitter threads and Instagram comments, RU4AR was called TERFs55 for saying “women” rather than “people who can get pregnant” or other gender-neutral language. They were called fearmongers for using violent imagery. They were accused of child endangerment for calling for teenagers to join protests that had any chance of getting hot. They were red-tagged as communist cultists for being linked to the RCP. They were called opportunists for forming in January 2022 and not being around as long as Planned Parenthood, ignoring the RCP’s decades-long history of defending abortion rights. These attacks were splashed all over social media (frequently by professional postmodernist political strategists, like Mary Drummer, a digital strategist for Planned Parenthood and MoveOn),56 providing an easy off-ramp for the young people who had been attracted to RU4AR to return to complacency. The postmodernist attack crushed any momentum RU4AR had achieved―and with it, the only attempt so far at igniting a militant mass movement for abortion rights post-Dobbs.

RU4AR replicated some of the RCP’s fatal flaws in that there was no plan to take their movement beyond badass protests, and certainly not to bring forth the young women it mobilized as revolutionaries. They stuck to their safe zone of major urban centers and never took the struggle to the most deeply affected women in the South. But the unhinged attacks on RU4AR by the pro-choice establishment and the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie had nothing to do with honest criticism.

Where are we going?

Our oppression will not be resolved by building a parallel, underground reproductive health service and DIYing our medical care. It’s not possible, and we shouldn’t have to accept that we can only access abortion in hiding. The point is to fight back against the entire Christian nationalist, revanchist package being forced on us, overthrow this rotten empire, seize state power and use it to enshrine and enforce the right to safe and legal abortion, and build a new, socialist society of which women are equal architects.

Since the struggle for abortion access affects the masses of women in life and death ways, and since the failures of the pro-choice establishment are so apparent, it can and should be a flashpoint for the radicalization of women for revolution. To build mass resistance against reproductive injustice, communists will have to clearly distinguish our line on abortion rights from that of the pro-choice establishment, and win over women who are deeply affected by reproductive injustice, and believe strongly that abortion must be legal, but don’t see a way for themselves to take action beyond voting or signing petitions.

Relegated to the shadows, abortion has been made embarrassing and shameful, and many people have conflicting feelings about it. The pro-choice movement, always on the defensive against the antis, doesn’t like to admit this, but a significant number of women do get abortions because of economic reasons or an abusive living situation, when in a better world they would choose to keep their baby. The best example of this is how the pro-choice establishment refuses to address the fact that Black women get abortions at higher rates than any other group.57 Many women absolutely have the clarity that they deserve the right to an abortion, regardless of how they emotionally experience it, but paternalistic attitudes on both the right and left traditionally refuse this complexity and tie the emotional experience to the morality of abortion. The pro-choice establishment insists that women almost never feel negatively about having an abortion, and reactionaries insist that women regret abortions and that they have to be protected from their own choices for their own good.

Both sides refuse women their own agency and deny the fact that women have the intellectual ability to make a tough call based on their own understanding of what’s best for their lives. In diving into this contradiction, we have an opportunity to truly understand the conditions of women’s lives that lead them to seek abortions, often at great personal risk and effort. We have an opportunity to dive into big questions of philosophy and ideology with people, exploring alongside them why “choice” is such an empty promise in a capitalist society. We also need to fight back against insidious gender essentialist ideology that insists all women want children deep down, or that a woman without children is incomplete as a human.

With the rise of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie to the political stage in the 2010s,58 and its denial of women’s oppression as a political issue, it has become popular for the pro-choice establishment, and social media Leftists in turn, to insist on using gender-neutral language to refer to the victims of reproductive injustice in the name of LGBTQ inclusion. Especially during the short-lived moment of protest leading up to Dobbs in 2022, people who understood that the oppression of women was at the heart of the abortion struggle and dared to use the word “women” were accused of trying to erase the experiences of transgender and nonbinary people who need abortions.

For sure, though the oppression of women is the central question in the abortion struggle, and abortion principally affects women, trans and nonbinary people are among those directly affected by reproductive injustice and should never be erased from the struggle for abortion rights. Furthermore, the Trump era has seen grotesque attacks on transgender people, often hand-in-hand with abortion bans; for example, Texas attempted to apply its “bounty hunter law” to encourage the harassment and intimidation of trans people by incentivizing private citizens to sue anyone they suspect of using the “wrong” public bathroom.59 These attacks are part of the overall reassertion of patriarchy epitomized by Dobbs, and illustrate how the oppression of women and LGBTQ people is intertwined, with LGBTQ people being demonized and punished for stepping outside the bounds of patriarchal gender roles.

However, referring to the masses of people targeted by abortion bans as “pregnant people” or, my least favorite, “uterus owners,” is not language that resonates with the masses of women and does not speak to anyone’s humanity. (Is it really “inclusive” to reduce people to their reproductive organs? The postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie continuously shows its true feelings toward the masses by using dehumanizing language, like “Black bodies,” to refer to oppressed people.) But the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie is interested in justifying their own capitulation through policing people’s language, not mounting viable, mass resistance to abortion bans and certainly not fighting for the rights and lives of trans people. Obscuring the root of reproductive injustice by denying that it stems from patriarchy and women’s oppression works for them because it signals to the masses that seriously engaging with gender politics is only for the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie to play with like a toy, and forestalls the possibility that these concepts could be widely, seriously understood and used to make revolution. We have to take control of how gender-based oppression is talked and thought about out of the hands of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie if we want to mobilize those among the masses who are directly affected by abortion bans and ready to rebel.

The upsurge of protest in the first half of 2022 showed that there’s a social base for militancy among young women and LGBTQ people who are ready for action and deserve to be trained up as revolutionaries. What leadership the RCP provided to this rebellious section of the masses was limited to Democrat-controlled states and liberal urban centers, where the liberal bourgeoisie is already content to pacify its base by enshrining abortion rights. To build a mass movement that really resists abortion bans, we need to move the center of gravity of the pro-choice movement out of the “shield law” states and liberal urban centers, and into the South and parts of the Midwest where women, especially proletarian women, are being most harshly affected, and collectively organize them under revolutionary leadership to fight back.

That revolutionary leadership should demonstrate that off-ramps to revolution offered to rebellious, dedicated young people by the pro-choice establishment, like nonprofit or academic careers, postmodernist theory, and social media Leftism, are all forms of capitulation to patriarchy, and that becoming cadre in the communist movement is the answer to the question “what can we do to fight back?” We can also make that same challenge—leave capitulation behind, help build a viable women’s movement—to any older feminists from the 1970s era, plus any fighters left from the 1980s/90s wave of militancy, bringing them together to help train young people and repair the generational divides between women.

A nascent militant women’s movement comprised of rebellious young people and fighters from older generations, collectively organized by revolutionary leadership, would then need to rally support from the broader masses of women, wrestling them away from bullshit parades and opportunist leadership that tells them voting and donating to political candidates and nonprofits is the best we can do. Bold action can help win over people who have a heart for women’s liberation but have become cynical and resigned to Pac-Man-politics-style resistance like underground abortion pill networks. This bold action can and should take the form of reviving abortion clinic defense, as well as politically targeting the specific politicians and cultural leaders responsible for legislating and enforcing abortion bans, exposing them, and punishing them (politically, for now).We can also use the militant history of the women’s movement to demonstrate that real agitation is far more effective than routinized rallies. And on the basis of rejecting opportunist leadership and capitulation in favor of militancy with a mass character, we can and must fight to overturn the Dobbs decision, make abortion legal again throughout the United States, and win real victories for reproductive justice.

To build a viable women’s movement more broadly, communists need to weave our own social fabric for our people and offer revolutionary collectivity as the solution to social isolation. Jan, the clinic worker in Ohio, pointed out to me that the Christian Right and the anti-abortion movement in general is really good at building social structures that draw people into their orbit. The Catholic church near her clinic, which organizes activists to harass her patients, also hosts pancake breakfasts and 5k runs, and they’re seen by many in the predominantly Black, proletarian neighborhood as pillars of the community.

As our society becomes more and more isolated and individualist, people are seeking human connection through social media, which appears to connect us while actually solidifying our social, emotional, and political isolation. The nature of social media is amplified in the case of conversation around women’s sexual and reproductive health; women go to social media for anonymous or semi-anonymous support, and to let off steam around vulnerable topics that we feel we can’t discuss openly in our real lives. These networks replace actual human connection and vent the pent-up rage that should be harnessed in service of revolution.

It’s striking that most of the really raw, frank, nuanced discussion of the realities of managing a medication abortion at home, miscarriage, problems with menstruation and birth control, and sexual politics in general, among proletarian women, is happening on reddit subs and Facebook groups. One Facebook group (I won’t name it because members have been harassed by antis and even doxxed) originally set up for women to get anonymous emotional support with complex feelings around abortion pre-Dobbs has now become a way for people in abortion ban states to spread word-of-mouth abortion resources and give advice on how to handle complications of medication abortions without getting arrested. Online spaces like these show how hungry we are for connection, and how willing we can be to really listen to the contradictions of other people’s lives. At the same time, they put us in the position where our most vulnerable and radical conversations are being monitored, surveilled, made available to law enforcement, and sold back to us via targeted advertisements. There is a disturbing irony to the fact that this turn to closed, online discussion is a retreat from unapologetic, public discussion of “women’s issues” while still being surveilled by the enemy.

The communist tradition has a long history of using mass meetings and speak-outs to bring together and radicalize our people. Perhaps the most striking example is how unapologetic discussion of the conditions of women’s lives, in both public and more private forums, was a cornerstone of women’s liberation during the Chinese Revolution. In the midst of wartime, communist women leaders in the Red Army organized women’s associations for peasant women to join together, share their stories and grievances, and confront patriarchal oppressors in their villages. “Speaking bitterness” meetings, where peasants gathered to aggrieve their conditions and collectively struggle against their oppressors (like landlords), brought women out of isolation in the home and into political life. Taking a page from their book and from the 1970s feminist movement, we likely need to start building a viable women’s movement for our time by bringing women, mostly but not entirely proletarian women, together, in person, to speak openly about the conditions of our lives, a la the consciousness-raising groups of the 1970s.

We know there is a real social base for militant resistance to abortion bans that has gone untapped by the pro-choice establishment; we know that historically, “unleashing the fury of women as a mighty force for revolution” has been essential to bringing forth a revolutionary people and overthrowing the capitalist-imperialist system. There is a crying need for a viable, militant mass movement of women, and we have all the tools we need to mobilize all our outrage. The website for ProPublica’s investigative reporting on abortion bans is covered with photos of the graves of women and girls who should still be here. The stakes could not be higher. It is past time to get seriously rebellious.

1Kavitha Surana, “Abortion bans have delayed emergency medical care. In Georgia, experts say this mother’s death was preventable,” ProPublica.org (September 16, 2024).

2Jennifer L. Holland, “Abolishing abortion: The history of the pro-life movement in America,” Organization of American Historians, oah.org (November 3, 2016).

3Our Bodies, Ourselves, “A brief history of birth control in the US,” ourbodiesourselves.org (July 23, 2020).

4Amanda Escotto, “Roe’s legacy: Feminism within the 1970s abortion movement,” happymediummag.com (March 14, 2024).

5Kristen de Groot, “Abortion and women’s rights 1970: A film that’s newly timely,” Penn Today, penntoday.upenn.edu (May 16, 2022).

6Jane Recker, “When abortion was illegal, Chicago women turned to the Jane Collective,” smithsonianmag.com (June 14, 2022); The Janes, directed by Emma Pildes and Tia Lessin, HBO (2022).

7Anne Rumberger, “The reproductive rights movement has radical roots: Interview with Nancy Rosenstock,” Jacobin Magazine, jacobin.com (May 11, 2023).

8Maggie Doherty, “Feminist factions united and filled the streets for this historic march,” The New York Times (August 26, 2020).

9Ebru Kongar, “Is deindustrialization good for women? Evidence from the United States,” Taylor and Francis Online, tandfonline.com (November 3, 2008).

10Planned Parenthood, “Historical abortion law timeline: 1850 to today,” plannedparenthoodaction.org (June 2022).

11Rebecca Goldman, “Abortion rights and access one year after Dobbs,” lwv.org (August 2, 2023).

12Kaiser Family Foundation, “US international family planning and reproductive health: Requirements in law and policy,” kff.org (July 26, 2024).

13Gallup News, “Abortion,” news.gallup.com (2023); Pew Research Center, “Public opinion on abortion,” pewresearch.org (June 2025).

14Emma Wallenbrock, “Inside The Handbook on Abortion,” slate.com (June 8, 2022).

15Carol Mason, From the Clinics to the Capitol: How Opposing Abortion Became Insurrectionary (University of California Press, 2025), 210.

16Ibid., 91.

17Ibid., 80.

18Ibid., 116; Suzy Subways, “Clinic defense in the era of Operation Rescue,” hardcrackers.com (July 28, 2022).

19Mason, From the Clinics to the Capitol, 159.

20Ibid., 149.

21Ibid., 161.

22National Abortion Federation, “Violence and disruption statistics: Incidents of violence and disruption against abortion providers in the US and Canada,” prochoice.org (2009).

23Angela Hume, “How abortion clinic defenders fought back against Operation Rescue in the 1980s,” slate.com (September 26, 2023).

24Marie Solis, “27 years ago, Roe v. Wade almost fell. This is how protests saved it,” vice.com (June 28, 2019).

25See Going Against the Tide‘s November 2024 editorial, “The reactionary repudiation of a restorationist program and the ongoing tantrums of two reactionary petty-bourgeoisies.”

26Subways, “Clinic defense in the era of Operation Rescue.”

27Paul Blest, “Republicans didn’t dismantle Roe alone. Plenty of Democrats helped too,” vice.com (July 15, 2022).

28Darragh Roche, “Barack Obama blasted for not codifying Roe v. Wade: ‘Dem failure,’” newsweek.com (June 25, 2022).

29Carter Sherman and Andrew Witherspoon, “Tracking abortion laws across the United States,” theguardian.com (November 24, 2025).

30Chicago Abortion Fund, “Three years post-Dobbs, Illinois is holding the line on abortion access,” chicagoabortionfund.org (June 24, 2025).

31Eunice Alpasan, “Planned Parenthood of Illinois closing four health centers, including Englewood location, amid financial shortfall,” news.wttw.com (January 22, 2025).

32Stephanie Taladrid, “The post-Roe abortion underground,” newyorker.com (October 10, 2022).

33Carter Sherman, “New Texas law allows residents to sue those suspected of providing access to abortion pills,” theguardian.com (December 4, 2025).

34Caroline Kitchener, “Antiabortion advocates look for men to report their partners’ abortions,” washingtonpost.com (January 17, 2025).

35Carter Sherman, “Louisiana issues warrant for California doctor accused of mailing abortion pills,” theguardian.com (September 29, 2025).

36Carter Sherman, “Texas midwife arrested for allegedly providing abortions amid state’s near-total ban,” theguardian.com (March 17, 2025).

37Rendala Alajaji, “She got an abortion. So a Texas cop used 83,000 cameras to track her down,” eff.org (May 30, 2025).

38Bracey Harris, “New study finds more than 400 pregnancy-related prosecutions after Roe’s fall,” nbcnews.com (September 20, 2025).

39Luis Prada, “Your period tracking app data is being sold and used against you,” vice.com (June 12, 2025).