A social investigation report from GATT readers in California

Camarillo is a city of near 70,000 people in Ventura County, California. The city is centered on a strip of apartment complexes, malls, public buildings, and boxy office parks along the 101 freeway that links the scenic Central California coast to metropolitan Los Angeles. On the northwest edges of Camarillo’s suburban sprawl lie country clubs and golf courses: playgrounds for rich, white retirees. South of the freeway, agricultural fields extend miles south towards the Pacific Ocean and Naval Base Ventura County, where the US Navy tests missiles, torpedoes, and other high tech weaponry. In neatly arranged rectangular plots (farmworkers call them los fildes), agricultural laborers spend their working days hunched over, straining their bodies to harvest the fruits, vegetables, and marijuana that sustain people in California and beyond.

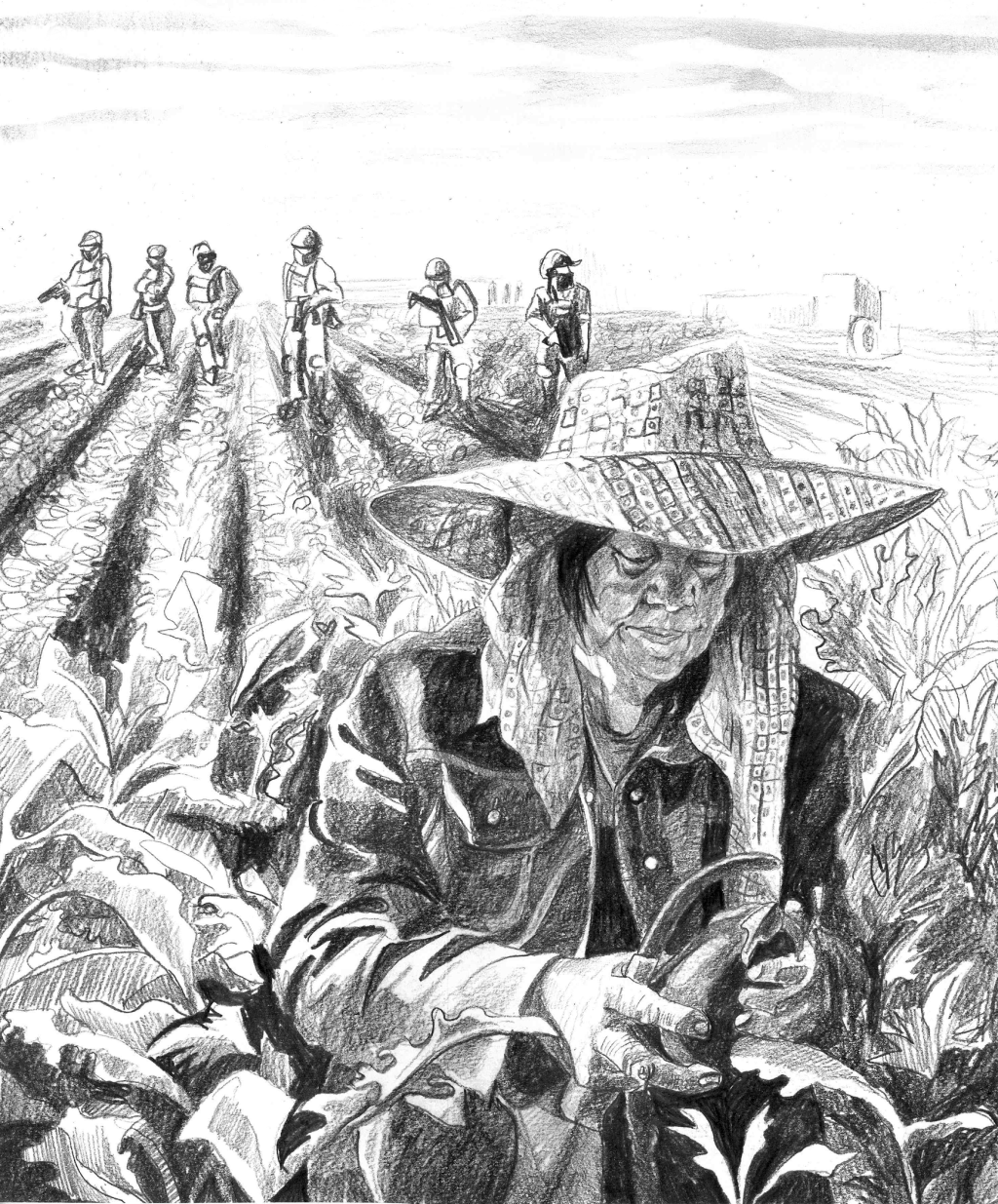

In July, ICE staged a raid in Camarillo at the largest marijuana farm in the state, Glass House Farms, capturing 361 migrants, including 14 minors. Families and neighbors of Glass House workers rushed to the scene, leading to an hours long confrontation as federal agents lobbed teargas into the crowd and showered protesters with rubber bullets. Nearly a dozen protesters were charged with assaulting or obstructing federal officers. One migrant worker, Jaime Alanis García, fell off a roof and tragically succumbed to his injuries the following day. After hearing about this incident, a group of Going Against the Tide readers went to Camarillo during the autumn 2025 harvest to take up the post-election call for social investigation among immigrant farmworkers from Latin America.

A problem with our approach to this social investigation was that we set out to learn what immigrant farmworkers think about what we think, and we mostly focused our questions on political events we were interested in. For example, we asked many people in Camarillo their opinions on the wave of sometimes violent immigration protests in June in LA that they had no involvement in. We also asked many people whether they believe in the abstract that revolution is possible. Not surprisingly, this approach garnered pessimistic views from the masses rather than drawing out people’s advanced views on how to end the oppression and exploitation they face on a daily basis.

In retrospect, we realize that the narrowness of our questions limited what we were able to accomplish with this investigation. We didn’t learn enough about people’s actual lives or how they see the world in a holistic sense. We should have focused on questions that would draw out a living picture of the lives and struggles of the people we spoke to, and their views on why things are the way they are and how people can respond collectively. Also, our framing of revolution as something that might just randomly happen someday was met with a lot of cynicism and pessimism from the people we spoke to.1 Despite the shortcomings of our investigation, we still hope that the information we were able to gather is a useful starting point for communists to begin to understand the lives of migrant farmworkers.

“They’re hunting us like animals”

On a sunny, dusty afternoon we approached a group of over a dozen Latin American immigrant farmworkers, men and women in their twenties and thirties, who were on break from picking a field of bell peppers. They crowded around a long table under an umbrella, eating from their lunch boxes and drinking sodas. Most were focused on their meal and didn’t want to talk to us, but one man, Tomás, spoke up. We asked him what he thought the biggest social issue in this country was, and he quickly launched into a condemnation of the immigration raids: “I don’t know why they’re hunting us like animals.” He disputed the official story that Jaime Alanis García died by falling, speculating that he was beaten to death by ICE. While the threat of repression loomed large in his mind, Tomás said the biggest problem is that people are so afraid of being deported that they aren’t going out and living their daily lives. “We have to go out and buy things and go to work. We need to defeat fear.”

Julio, a middle-aged immigrant father, told us he knew thirty people who were taken by ICE, and many others who had left the country in fear. Julio said that he’s lived here for twenty years, and these immigration raids are the worst he’s ever seen. He’s afraid of getting deported since he has a family here that he provides for. He’s caught between wanting a better future but not seeing a way out.

Julio’s experience was echoed by Pedro, one of his coworkers in the bell pepper fields. He told us that he feels a lot of fear. He’s been in the US alone for three years, but knows many people who returned to their home country because they were afraid of being deported. Pedro angrily rejected the idea that ICE is focused on deporting criminals. He told us it was already hard to begin with coming to the US, and now the government is making it even harder by targeting workers like him. He’s expecting to have to go back to Mexico eventually, whether voluntarily or not. His attitude is that he’s lucky to still be in the US and he’s going to make the most of that while it lasts.

We spoke with a woman after a Catholic Mass conducted in Spanish who had more conservative religious views on deportations. When asked what she thought about the ICE raids and deportations, she agreed that they were bad, but said that abortions and murder are bigger problems than immigration raids and deportations because at least deporting a person still lets them live. She insisted that the solution was prayer, not fighting, that we need to pray for immigrants to act like better citizens so that they don’t get deported, and she asserted that many immigrants commit crimes and then go on to commit further crimes when they get deported to their home countries. She got her papers recently and prays for those who don’t have them yet.

Another churchgoer, Alejandro, wanted to talk about the Glass House Farm raid. He held the ICE agents responsible for Jaime Alanis García’s death. “Why is it that when they kill someone, nothing happens to them, but when someone like you or me kills someone, we go to jail?”

A common attitude we encountered, not just among the church crowd but among many of the immigrants we spoke to, can be summed up as “I’m leaving it all up to God.” One farmworker woman we spoke to said that it’s in God’s hands whether or not any individual gets deported. More than one farmworker said that if people get picked up by ICE, “that’s their time.”

On governments and politicians

Adolfo came to the US in 1995 with his family and was working in pool construction when he lost most of his leg in a workplace accident. His family now lives in New York, while he lives in his car in Camarillo. We talked to him outside a market where he was begging from his wheelchair. He guaranteed us that things would get better once Trump gets voted out of office. Asked what immigrants who can’t vote can do about the situation, he replied: “They can’t do anything. All they can do is vote in their home countries.” While Adolfo was optimistic about the post-Trump US, he recognized the need for deeper and broader changes: “The government needs to change, not just here but in all countries”. He sees all politicians as bad, but says corruption is much worse in Mexico than in the US. He pointed to the Mexican government allowing street violence to reach alarming levels, where he’s afraid for kids to go outside.

Inside the market we spoke with Abram, a Mexican immigrant shelf stocker. When we asked him what he thought was the biggest issue today, he surprised us: “People think that we’re citizens first. We’re humans first, we’re citizens second.” According to him, people view things in terms of what is legal and what is not, when what really matters is our common humanity. When we asked him what needs to change, he reiterated: what needs to change is “the fact that people think that before they get treated equally, they need to follow the laws.”

Tomás told us that “all politicians lie. They say what the people want to hear, but in the end they’re not gonna do it,” before proudly declaring, “I’m against the government.” When we turned the conversation to how to fight back, he suggested that people should not pay taxes, since their work pays for government officials and wars. “The government does what they want with us because we do nothing.”

Quality of life concerns and discrimination

One evening, our group checked out a Little League baseball game, where mostly middle-class fans of different nationalities cheered on their elementary-aged children. Some sat at the edge of their seats while others reclined on their lawn chairs, heads slumped towards their phones. But Patricia had work to do. She was cleaning the park bathroom when we struck up a conversation with her.

Patricia came to the US because she was trying to get a better life for her kids and get away from the political corruption in Mexico. She says that there isn’t any work for people over the age of 35 where she was, so she migrated thinking she would have better luck getting a job in the US. She’s working now, but she still feels squeezed by rising prices and looked down on by her white neighbors. She pointed out Little League parents glaring in our direction and speculated it was because we were speaking Spanish. “But when are you gonna see a white person or somebody with papers working on a farm, feeding people, removing pesticides for people?” She says that groceries and other basic necessities have been way too hard to afford ever since the pandemic and was especially worried about what the government shutdown and political maneuvering would do to food stamps and Medicaid. According to Patricia, everyone who’s on top looks to see what profit they can make from anyone they’re oppressing.

Our conversation was abruptly cut off when a park ranger approached her and began barking orders at her to move her car, despite her explaining that her managers allow her to park there.

Tomás also rejected the racist vilification of immigrants, specifically how immigrants are painted as the source of unemployment for US citizens: “We don’t take away anyone’s job, because people here wouldn’t take those jobs anyway.”

After his workplace accident, Adolfo couldn’t work and had to pay for his care out of pocket. Now his doctor visits and prescriptions are covered through Medi-Cal (California’s implementation of the federal Medicaid program), but he receives no other assistance and depends entirely on begging to feed himself. His biggest concerns were the rising prices of basic necessities and potential further cuts to the social safety net. Adolfo has a lawsuit still going against his former employer because of the accident, decades after his injury. He says he wants to go to Mexico “as soon as possible,” once his suit is over, but is afraid of being deported because of the disruption that would cause to his case.

Abram, the shelf stocker, said that the state of Mexico that he came from is “very dangerous” because of cartel violence. He came to the US when he was eighteen, when his father hooked him up with a job. But his father returned to Mexico a few years ago, and now Abram has no family here. He told us about a friend who left a small pueblo (rural town) in Mexico with no cell phone service to come to the US when he was thirty. He quickly became depressed because he couldn’t stay in touch with his family, and returned to Mexico within months. We asked Abram if he was depressed himself. He said that at first he was depressed when he came to the US, but eventually he got used to it. He attributed his depression not to isolation from his family but to larger political and social issues in the world. “When you’re alone it’s better,” he said, “since you don’t have to worry about ICE raids separating you from your family.”

“Is revolution possible?”

We were open with the people we talked to that our investigation was part of a revolutionary strategy: we want to understand the situation in order to change it. When we mentioned this to the group of farmworkers, Tomás excitedly butted in: “Revolution? That’s great, let’s start a revolution!” His friends exploded into laughter at this outburst, but his enthusiasm was genuine. We asked the group what it would take to make a revolution, and this finally got Tomás’ coworkers talking. Tomás said “un líder” (a leader). A coworker chimed in: “unión.” (unity). Another piped up “la fuerza” (force).

We asked what one can do in the here and now to work towards a revolution. Tomás said “do what you’re doing now, talking with people, getting together”. He pointed to Martin Luther King as an example of the kind of leader he’s talking about. According to Tomás, “before MLK, Black people suffered racism. Now, they are equal to whites. That’s what we (immigrants) need to do.”

Julio had a more lukewarm view on the possibility of revolutionary change. When we asked him about protests against the ICE raids, he said that ICE agents are “just doing their job” and objected to more militant resistance against the raids, even as he sympathized with protesters who have been arrested. He says he doesn’t see much of a role for immigrants of his generation, because they don’t have a position to “get even” with ICE, and “we have to follow the laws.” Julio says that the children of immigrants are the main ones fighting for justice, more so than their parents. At the same time, he said he feels betrayed by the roughly half of Latino voters who went for Trump in 2024, and he was one of many people who expressed shock and confusion at reports of Latino ICE agents and cops. At one point, he said “I just have to do my part in having hope,” but it seems like his hope is less for himself than for the possibility of future generations finding success within the system.

Patricia told us she wants to have hope that things will change, but she doesn’t know if that will happen. Everybody is too busy looking out for themselves, getting their own needs met, so they don’t have time to think about what they can do for others. She pointed to the continuing genocide in Gaza and expressed frustration that each new round of ceasefire talks fools some people into thinking the horror is over. “The ceasefire in Palestine is just words! What’s that supposed to do?” Patricia may be pessimistic, but she is proof that there are proletarians out there thinking broadly about the state of the world, not just their own situations, who want to stand with the people of the world and can see through the bourgeoisie’s bullshit.

Another man we spoke to outside the market where we met Adolfo and Abram was much more content with the state of the world. He was adopted and came to the US with his mom when he was twelve. He is a citizen as well as a Vietnam veteran, so he doesn’t feel affected firsthand by the deportations. His attitude is that he’ll ride out the Trump presidency, and things will simmer down once he’s out of office. He doesn’t believe a revolution is possible because minorities are really divided. He said there are classes within minorities, and they oppress one another, saying “I know because I’ve done it before.” In his experience, he’s seen that minorities start to integrate themselves into life in America. There are divisions among Latinos: some are making more money than others, some have papers while others don’t.

Many people shared the sentiment that divisions among the people are the primary barrier to revolution. For example, inside the market, when we asked Abram if a revolution was possible, he said “that’s really tough. I believe it couldn’t happen” because “the people are so divided, but the government is so united.” “If people were more united, then maybe. But many people are extremists.” He did not elaborate what he meant by “extremists,” but said that people had tried revolutions many times and that each time it ended badly. In particular, Abram pointed to the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre, when the Mexican Armed Forces opened fire on a group of peaceful protesters, mostly students, who were occupying the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in opposition to the upcoming Mexico City Olympics. Hundreds were killed. Eventually, he conceded that “not in Mexico, but maybe in other countries” and “not now, but maybe in the future” revolution might be possible.

Like Abram, other people we talked to shied away from the violence of revolution. When we asked Adolfo what he thinks about revolution, he said “You mean a war? No, many people would die, including children.” His conception of revolutionary violence wasn’t about popular uprisings to shape a new society but rather the kind of gang warfare that ravages Mexico. Whether or not they had papers, most of the people we talked to described political action as fundamentally limited to exercising voting rights and, at most, engaging in peaceful protest. Again, it’s hard to tease out whether this outlook is as prevalent among immigrant farmworkers as our investigation found, or if it was over-represented because our questions were skewed to begin with.

When we asked a family spectating the Little League game what they thought was the biggest issue going on in the world right now, a woman said “Our world right now is this baseball game.”

“Muy pocas esperanzas”

In Camarillo, immigrant workers are caught on the threshold between two worlds that offer them little hope for the future. In Mexico, the home country of all the immigrants we happened to speak to, they faced mass unemployment, grinding poverty, and the constant threat of violence. In the US, they work long hours in harsh conditions while being paid the bare minimum and looked down upon by their neighbors. Some place what few hopes they have in the Democrats, future generations, or salvation from God. At the same time, they feel squeezed by climbing prices and cuts to welfare and betrayed by more integrated Latinos pulling up the ladder behind them. Many live in constant fear for themselves and their families, but others treat the prospect of their own deportation with casual indifference, resigned to the impermanence of their life in the US. They live in a hostile society that presses in on them from all sides and subjects them to racist mistreatment every day. They feel the spiritual poverty and depression that comes from jumping from job to job without a chance to build meaningful relationships over the long term, often thousands of miles away from their families. Even Tomás told us sadly that he has muy pocas esperanzas (very little hope) for the future.

This initial investigation provides a look into how immigrant proletarians in Camarillo view big-picture political problems in the world and especially the recent immigration raids. The immigrants we spoke to don’t see any avenue for themselves to take action within the system, and they see little hope for the future. That’s what makes them a prime social base that must be organized by communists to fight for their only true hope: the revolutionary overthrow of this system that makes their lives hell.

1Note from the editors of GATT: belief that a revolution is possible in the abstract is idealist, while the knowledge that revolution can be made through the conscious initiative of the masses under the leadership of a vanguard party is materialist (it’s a historical reality, not a religious belief). The proletariat as a class has a keen bullshit detector, and is not going to respond enthusiastically to idealist bullshit, which is why it’s not surprising that a question about revolution asked in this way elicited cynical and pessimistic responses. In other words, immigrants working the fields have the proletarian sense to know that revolution, like the autumn harvest, has to be produced by people.