A social investigation report from GATT readers in NYC, January 2026

Jackson Heights is a bustling neighborhood in Queens, home to people from all backgrounds and nationalities. One of its busiest areas is the Roosevelt Avenue transit hub, where a bus terminal sits next to the large, criss-crossing train lines that connect Queens and Manhattan. People coming off trains transfer to buses that take them deeper into the outer borough, or they walk down Roosevelt Avenue and visit the various immigrant-owned shops and restaurants that line the streets. This is perhaps the most defining aspect of Jackson Heights—it’s made up almost entirely of immigrants. And while there’s a visible layer of relatively stable immigrant businesses, the blurry hustle and bustle of the immigrant masses in the streets is really what defines it.

During the day, street vendors line the blocks selling everything from lollipops to tacos to drugs. At night, prostitutes wait on corners for business to come. The people of Jackson Heights may arrive from various countries and make their money in different ways, but more and more of the people living there have arrived only in the last few years from places like Ecuador and Venezuela. And instead of the land of opportunity exported by the US via Hollywood movies, TV shows, and social media, they’re met with meager living and a vicious deportation machine that succeeded in deporting half a million people in Trump’s first year in office in 2025.

Our social investigation team based in New York City went to Jackson Heights, then into the subway, then straight into the heart of the deportation machine at 26 Federal Plaza to learn about what immigrant masses are facing, what they really think, and what we, as communists, can do to meaningfully intervene. We applaud the courageous efforts of people around the country who have stood up to ICE to defend migrants from deportation, and we were particularly inspired by bold resistance and combativity of the masses in LA in June. But in the face of this continued onslaught, the big question for us is: how can we forge the immigrant proletariat in the US into a revolutionary people to fight back against it?

How we got here

The number of migrants arriving in the US is higher than it’s been in decades, but the reasons for this migration have remained consistent. Millions of people have little choice but to flee their home countries in order to escape nightmarish conditions of poverty, violence, and war. These conditions are a result of the various ways US imperalism has wreaked havoc on the world, destabilizing the lives of hundreds of millions of people in Latin America, Africa, and beyond, leaving them with little to no opportunities for a safe, fufilling life. They come to the US, sometimes alone but often as families with small children, with the hope of a better future. Instead, they are met with a new nightmare.

Upon arrival, immigrants shuffle through different kinds of temporary living accomdations, such as hotels, shelters, and refugee camps. For example, the Midtown Roosevelt Hotel, which closed in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, reopened in 2023 to provide temporary shelter for migrants in a lucrative deal in which the city paid $202 per room for more than 155,000 migrants who passed through, totaling $220 million over three years. When it was finally closed as a migrant shelter, people staying were either relocated to the refugee camp that had been set up in Randall’s Island, sent to another city-run shelter, or left out on the streets.

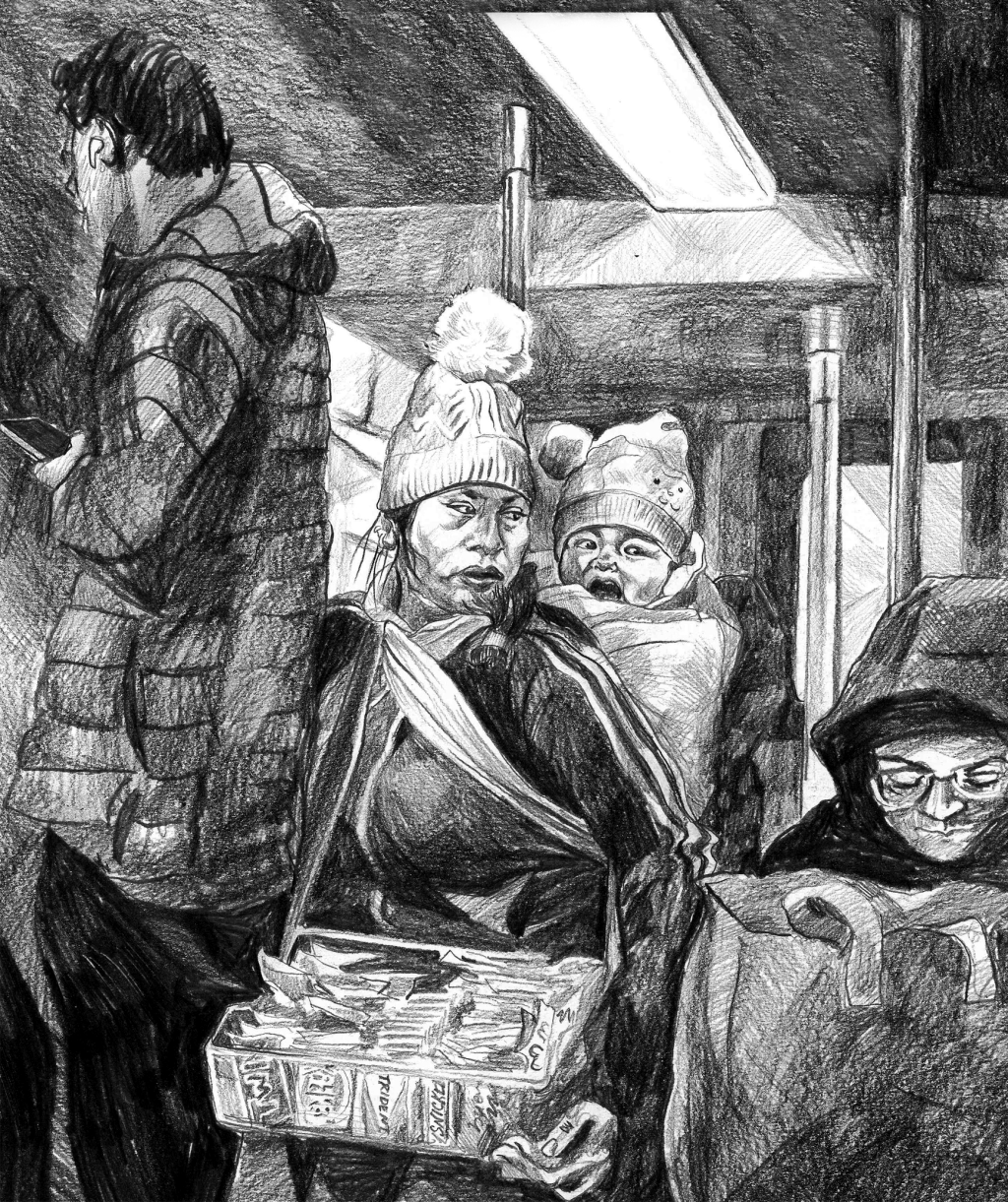

Struggling to find jobs and steady employement, many recent arrivals resort to working on the streets, selling food, candy, and other merchandise, without any certainity of how much money they will earn that day. Women selling snacks on the subway have no alternative than to bring their children along because they don’t make enough money to afford childcare or any kind of support. We spoke to several street vendors and found that even with a spouse, the responsibility for childcare is on the mother while the father is out working or looking for work.

In the case that they find employment, immigrants in the US face disrespect, abuse, and exploitation under employers who take advantage of people’s desperation and fear of deportation in order to get cheap labor. While it may bring a sigh of relief, finding employment does not guarantee any stability, as they can just as easily be cast aside and end up right back where they started. Despite being driven by perserverance and hope for a better future, life is plagued by uncertainity and instability.

This has long been the common experience of immigrants in the US, but since Trump’s second term as president those conditions have been compounded by new levels of fear stoked by reactionary propaganda and inflammatory media coverage of deportations. This is why we decided to go out and find out how this fear is affecting immigrants, how their lives have changed since the start of 2025, and what we can do about it.

The vendors

In Jackson Heights, our social investigation team went to Roosevelt Avenue to see what things were like for people on the streets of a proletarian immigrant neighborhood. Florists and drug dealers who set up shop told us “estamos aquí tranquilos,” which means “we’re alright here.” But we also heard the opposite sentiment from a lot of people, especially older people. One man who had been here forty years told us people have been afraid of going out to find work and even to buy groceries because they’re worried about getting snatched by ICE. He told us how ICE sometimes poses as contractors and lures people in who are looking for work. People used to feel a lot more free to go out and about, and that’s changed. But despite the fear, he told us that “en la unión está la fuerza,” meaning there’s strength in unity. We asked him, “If there was ever an opportunity to fight back, would you be a part of it?” He said, “Claro que sí.” And when we brought up the protests in LA in June as an example, he told us that protests like that happen spontaneously or they don’t happen at all, but that if it could happen in LA it could happen here.

We met Carmen close to the train station selling lollipops. If you’ve been to New York over the last few years, chances are you’ve seen women on the subway selling candies and sliced fruit. But unlike those women who often hustle in train cars while carrying their children on their backs, Carmen is a little older and stays put with her merchandise. She came here from Colombia two years ago under the impression that there were a lot of good jobs for older people in the US. Back home, she worked odd jobs cooking, cleaning, and taking care of children. But when she moved here, nobody would hire her because of her age. She turned to selling lollipops because she can’t carry anything heavier—if the police try to get her, she can’t get away with anything else. The candies are the cheapest and easiest thing for her to sell, but she’s lucky if she can sell enough to get by.

Carmen talked to us about the other people she’s seen since she’s been here. When it came to the widespread prostitution on Roosevelt Avenue, she said she would never do that herself because of her religion. But she was very understanding and lucid about it, saying that women are only doing that because they have no other choice. It also wasn’t an option for her because of her age and appearance. There are older women that do it, but they have to get plastic surgery. Her stark assessment was that “there are a lot of young, able-bodied girls selling themselves on the street. If they can’t get a job, how could I? It’s a jungle out here, the way people are struggling. It’s not even this bad back home.”

She told us she doesn’t want to be here, she just wants to make enough money to get groceries and buy herself basic things. But on top of her age, she talked about her technological literacy being a major obstacle for her getting access to potential resources. “There are people who come here and have spent less time than me but they know where to go or what to look for to get help.” People have helped her and have tried to show her where she can get help, but she can’t do it on her own and can barely get around. “They’re getting apartments, clothes, and other benefits that I can’t get.” She pointed at a man walking down the street and said, “do you see that guy? Last month he was in the same position I’m in, and now he’s walking around with a chain.”

Carmen opened up to us about a lot of things. She had spent time on Randall’s Island back when a plot of land was set aside as a camp for recent arrivals. It was a shit show. An informal economy grew out of need, and the guards and employees working there were in on it to make a cut, selling brand-name items and electronics they got from the outside. People preyed on each other, stole things, and there was no privacy. It was like a bunch of people were just piled on top of each other with no space between the cots they were given to sleep on. The cots were low to the ground, which made it hard for her to stand up as an older woman. She told us about couples having sex right next to her, people coughing on each other, and sketchy shit going on all the time. Far from the idyllic view of the US, the Randall’s Island camp was a nightmare, yet somehow things are still getting worse for recent arrivals. Two years ago, Democratic politicians in NY were handing crumbs to recently arrived immigrants in the form of temporary shelters and asylum applications. Since then, cities like New York stopped housing migrants in hotels and camps altogether. Now, migrants are just left to fend for themselves, the temporary shelters are closed, and asylum applicants are being targeted for deportation.

“This is your country:” State power inside 26 Federal Plaza

When you think of immigration raids and kidnappings by ICE agents, you might be thinking about migrants getting pulled out of their homes or workplaces. Although those encounters do make up a significant portion of deportations, since the start of Trump’s second presidential turn, the day-to-day functioning of the deportation machine increasingly relies on detentions at routine court appearances, third-party deportations, and the “de-classing” of different immigration statuses.

In New York, the federal government has built a fortress out of an immigration courthouse and tucked its deportation machine away inside. Half of all ICE detentions in New York City start in only one building: 26 Federal Plaza. Our social investigation team went down to 26 Federal Plaza to talk to people waiting for court, to see what things were really like on the inside, and to learn about how the deportation machine actually functions.

Detentions at routine court appearances

Picture this: you’re an immigrant reporting to your regularly-scheduled immigration hearing. You might be in the process of applying for asylum or already on your way to becoming a legal permanent resident (obtaining a “green card”). You have a lawyer, and you’ve been summoned to immigration court for procedural matters. You appear in front of 26 Federal Plaza, a huge building near Manhattan’s City Hall used by various government agencies, including the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), an Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) field office, and an FBI field office. When you get upstairs to one of the two floors where all the immigration courtrooms are, you come face to face with about a dozen masked ICE agents. These burly corn-fed thugs don’t pounce on you right away; they’re just waiting for the right opportunity. Regardless of what happens at your court date in front of an immigration judge, whether they overturn your deportation order or even if you never had one to begin with, once you step back out into the halls of 26 Federal Plaza, ICE can snatch you.

Don’t ask us what the legal basis for this is; it doesn’t exist. They do whatever they want and nobody is stopping them. Not the mayor, not the governor, certainly not the police. Up and down the ladder of bourgeois-democracy, there is no savior from federal immigration enforcement.

On the inside of 26 Federal Plaza, we met people from all over the world: a Venezuelan family, a Haitian family, and men from Guyana, Ghana, Hong Kong, and Vietnam. There was a mix of people who had deportation orders and those who didn’t, people who had seen the news about mass deportations and were afraid and others who didn’t seem to know it was happening. Routine court dates are more stressful for people now, not just because of the ICE presence, but also because people have shown up and gotten their passports taken from them, leaving them without documentation.

When we made it upstairs to where people had court, we found ourselves in the middle of about a dozen ICE agents, masked and armed to the teeth, along with 5–10 press photographers. As soon as we arrived, one of the ICE agents agressively told us that if we wanted to be there, we had to stand out of the way in a little waiting room off the hallway. The formal immigration process dictates that a judge makes decisions on a person’s status and what happens to them corresponds to that decision. With that formal process broken down by the absolute power ICE wields, immigration judges have become accessories to kidnapping. In the waiting room, we met an interpreter who had been working there for a few months, and he told us that “judges know what’s happening right outside their door. Once they come out, they just grab them.” One of us (naively) remarked about how New York is a sanctuary city, that we just couldn’t believe this was happening here. With a knowing smile on his face, he said “this is your country.” He told us how that very same day, there was a Wolof speaker wandering the building for two hours. She didn’t know where her court appearance was taking place, and ICE took her because she didn’t have an interpreter. We didn’t wait to see any of these kidnappings ourselves; we couldn’t stomach standing by while it was happening, knowing that if we even tried to get in the way we wouldn’t stand a chance.

Third-party deportations

We met a man from Hong Kong with no passport and no pathway to legalizing his status in the US. He came here as a child with his father, and when he was fourteen he was charged with a felony, tried as an adult, and convicted. Since being released from prison after serving time for that charge, he’s had an open deportation order, but he can’t be deported because his country of origin won’t accept him (due to a technicality with the political status of Hong Kong, China does not accept returns of people with Hong Kong passports). Caught between a country actively trying to deport him and a country that won’t accept him, he’s been detained by ICE on three separate occasions across multiple states. Every time they’ve detained him, they’ve held him for the maximum six months, only to release him out of necessity. He’s scared of being detained and going through it all again. “This isn’t a life,” he told us.

Cases like these have recently been subjected to third-party deportations, meaning that if someone can’t be deported to their country of origin they can be deported to a participating “third party” country like South Sudan, El Salvador, and Panama. These junior-partners of US imperialism receive a “surplus” population from the US in exchange for cash and diplomatic favors, whether they enter into that agreement voluntarily or under coercion by the US.

De-classing of different immigration statuses

We spoke to an older Cuban immigrant, Pedro, who came here twenty years ago. From time to time, he’s ordered to go to 26 Federal Plaza to “check in” and get a paper signed by an immigration official. But the last time he showed up, they told him to go home and tried turning him away without even letting him enter with his English interpreter. He was furious and refused to leave without having his paper signed. “You’re telling me I have to go home when I’ve been doing this for twenty years! Do they think we’re stupid? If I go home without this signature, they could put a warrant out for my arrest and deport me.”

While Cuban immigrants in the US used to get better treatment from immigration authorities due to their status as fleeing a “communist” country,1 these measures have been rolled back over the last few years and evened the playing field, in a negative sense, for all immigrants. Consequently, those who once came and got settled here with very little problems are now facing a crackdown alongside immigrants from places like Haiti and El Salvador who were never given that special treatment to begin with. This kind of “de-classing” of previously protected immigration statuses has been happening across the board, not just to Cuban immigrants. It can also be seen with the dismantling of previously protected legal statuses, such as the end of DACA, the announcement of a $100,000 application fee for H1-B visas for skilled workers to stay in the country, and even the revocation of Temporary Protected Status for Haitians and Venezuelans.

Deportation and despair

When we asked people about what we can do to stop the deportation machine, and what the role of immigrants is in that fight, we got mixed responses, but we specifically noticed a lot of hopelessness that things could get better on the one hand, and on the other, somewhat conservative beliefs across the board about immigrants as a group and whether they even deserve better. These contradictions in many immigrants’ subjective outlooks, which have been planted by years of living with uncertainty about their future and extreme precarity, and cultivated by the spread of revanchist propaganda throughout American society and including among immigrant populations specifically, are some of the biggest barriers to developing the revolutionary class-consciousness of the immigrant proletariat.

One migrant we spoke to outside 26 Federal Plaza had a deportation order and an ankle monitor on. He had only spent two and a half years in the US, but things have just gotten worse since he arrived. He thought it was really fucked up how immigrants were being treated, but when we asked if we should be protesting more like people were doing in LA, he said it would be a bad look and would only “prove them right” that migrants are violent. His sentiment was that protests should be peaceful, because “as immigrants we should respect this country.” The idea that immigrants don’t have the right to intervene in this country’s politics was shared by several of the people we talked to.

Another argument we heard repeatedly from immigrants for why they shouldn’t rebel was a religious one. Many expressed the sentiment that “it was god’s will for me to come here, and if I’m deported, that will be god’s will too.” Whether for legal or religious reasons, we found ourselves arguing for the “right to rebel” against a widespread sense that immigrants should just keep their heads down and hope for the best. Rebellion is seen as too dangerous, as giving immigrants a bad rap, or as morally wrong2 in the so-called land of opportunity. The reality is also that for some people, the worst of the system here is better than what they left back home. That tradeoff, the one that every immigrant hopes for when they arrive, is part of what’s held people back from confronting the system.

Some people believed there were “good” deportations (of criminals, for example) and other “bad” deportations (of innocent people). “Good” or “bad” immigrant narratives—the (real and imagined) divisions among the people—miss the mark on who the real criminals are. They reinforce the legitimacy of the deportation machine that we’re told is meant to deport the “bad” immigrant, but actually functions to tear people apart from their families and communities. Exposing that narrative means uncovering who our real friends and enemies are, an important step to take in raising the overall class-consciousness of the masses.

One man we spoke to who had an active deportation order was scared because his routine court date had suddenly been moved up a year without explanation. Still, he said that all people could or should do is “go through the process.” You could feel the hopelessness in the air—immigrants and lawyers alike felt they had no other option than to accept what the immigration system decides. Whether expressed through religious sentiments like “it’s god’s will” or that there’s nothing to do other than go through the system, the despair itself limits what kind of action people think is possible for them to take.

“Everything relies on us”

Pedro, the Cuban immigrant we spoke with, said something very insightful, something that we heard echoed by many immigrants we talked to during our our social investigation: “Without us, none of this would work. We work our asses off in construction, picking crops, cooking in kitchens, and cleaning up after everyone else. If we get kicked out, would these Americans pick up the slack? No, they’re just trying to keep us in our place. Everything relies on us.”

All over the city, all over the country, immigrants are the backbone of American life. The parasitism of imperialism, our quality of life here, is only afforded to us because of their brutal exploitation coupled with the subjugation of the oppressed nations they come from. So many immigrant proletarians see that they are essential to the functioning of the system. Because they are so essential, the deportation machine has been set up to beat them into submission, enforce permanent precarity, and do away with any “surplus” population that could swell up and spill over into a mighty stream sweeping away the old order. The deportation machine exists so that immigrants don’t dare to step out in any way that would harm the system.

Based on our investigation, we found the basis for organizing the immigrant proletariat for revolution in the US to be their pride in their role in US society as well as their consciousness of their power as a class. With so much holding them back, objectively in the form of horrifying conditions and attacks, and subjectively in the form of fear and despair, anchoring our efforts in this powerful understanding of the unique position of the immigrant proletariat can help us overcome those contradictions along the road to forging a revolutionary people.

“Everything relies on us.” Not just capitalism-imperialism, not just the parasitic way of life afforded to people living in the heart of US imperialism, but also the prospect for proletarian revolution in this country. Grasping that with confidence and developing that class-consciousness far and wide is the only way to collectively square up to face down against the most evil empire in human history.

1The Cuban Revolution was an inspiration to millions of people all over the world for overthrowing the US-backed Batista regime in 1959. That, combined with the Cold War alliance between Cuba and the Soviet Union, made the US hostile to the island ninety miles away and eager to make itself look like a humanitarian protagonist for taking Cuban immigrants in. But claims that Cuba was or remains a “socialist” country rarely address what we even mean by “socialism” and how Cuba actually went about its development (doubling down on its dependency on sugar and other cash crops for Soviet “aid”). For a deep dive into the subject, we suggest reading Burn Down the Cane Fields! Notes on the Political Economy of Cuba, published in A World to Win #14–15 (1989–1990) and available online at goingagainstthetide.org.

2“Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s” (The Bible, Matthew 22:21). The notion that people should submit to the law of the land is foundational to Christianity and might help explain the ideological roots of this kind of thinking among immigrants from Latin America owing to Christianity’s widespread influence.