By Opal Skinnider

GATT Pamphlet series, published November 2025

The following pamphlet is available for download as a PDF, and we urge our readers to take up the task of popularizing the achievements of socialist China by printing and distributing it.

What would it look like for an entire society to throw down in the struggle for women’s liberation, together? How does half the world’s population go beyond fighting for our liberation as a niche issue to uprooting patriarchy at its foundations? How can we possibly overcome millennia of patriarchal rule in all its different forms, and transform ourselves in the process?

The Chinese Revolution and the socialist state it established from 1949 to 1976 provide inspiring answers to these questions. In the course of overthrowing the old order and then building a new society based on equality between women and men, women’s liberation was woven into every aspect of the revolutionary process. Under the leadership of the Communist Party, the fury of women against patriarchy and all forms of oppression was unleashed to radically transform society from top to bottom.

What was it like to be a Chinese woman before the Revolution?

Women in pre-revolution China lived in a feudal system beholden to the reactionary laws of the ancient philosopher Confucius. “Filial piety,” a person’s obligation of loyalty to their parents, formed the molecular structure of the oppression of the poor and the peasantry. This was widely accepted as the basis of an orderly society: children were to serve their parents, wives to serve their husbands, and, ultimately, men to serve their rulers. Sound familiar? Readers in the US should hear echoes of the most right-wing, reactionary formulations of family life spouted by podcasters and fascist politicians today. It’s not that these intensely patriarchal ideas were unique to China; many philosophies since the dawn of class society undergird patriarchal family models to encourage the submission of women and children to men, and then the submission of the oppressed class to the ruling class. Confucian ideology lent itself well to entrenching a regressive society in China, where the debasement of women within their families was reflected in the wider debasement of the masses at the hands of landlords, other petty local tyrants, and, beginning in the nineteenth century, foreign imperialists and their local lackeys.

Girls were raised to be married, often as young children, to men their fathers chose, or to be sold by their families into concubinage (sexual slavery) to wealthier, more powerful men, or outright prostitution in the cities. New wives worked for their in-laws like slaves, and could only hope to one day produce a son and eventually have a daughter-in-law of their own to oppress. Women were overall regarded as inferior to men, and could not expect an education or even to be taught how to read. When the poorest families weren’t able to feed a new baby, they might be forced to sell, abandon, or kill baby girls in order to try again for a boy. In the upper classes, foot-binding robbed even the most privileged women of freedom. Foot-binding was a process where a baby girl’s feet were tightly wrapped until they lost circulation and the tissues died, resulting in women with small, crushed feet. For upper class women, these small, crushed feet symbolized their status of not having to work, but also kept them subservient and unable to run away. Women had no place in public life and were confined to their fathers’ or husbands’ homes.

It probably isn’t surprising that suicide was a common way out for young women, especially new brides. In 1919, Mao Zedong, who went on to become the central leader of the Chinese Revolution, wrote about the suicide of a young woman known as “Miss Chao,” who died trying to escape an arranged marriage. Mao wrote that her “original idea” was “to seek life” not death; that their society had formed an “iron net” to trap her. As the revolution kicked off and people all over China entered into the struggle for a new world, this realization that the subjugation of China depended on the subjugation of Chinese women, and that women were ready to rebel with their lives rather than their deaths, would bring revolution right into people’s homes and villages. Communists were about to explode the revolutionary potential of the masses of women out into warfare, into production, and into cultural life, transforming women and men, transforming China, and clearing a path that the rest of the world could follow.

Women’s liberation in every part of the revolution: not a second to waste

And as there was a Gold Flower, more or less, beaten and bruised, saddened and soured, in every farm in North China, she became a portent. The Communist Party saw her and schemed to serve her and themselves through her. She was that spirit that forgets nothing and forgives nothing. There she stood at her gate, slow-burning revenge incarnate, waiting for a better time, waiting an opportunity.

– Jack Belden, China Shakes the World

Among the rebels involved in China’s May Fourth youth movement of 1919, some went on to form the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and encouraged the education of women as part of a broadly progressive and “modernizing” agenda. This gave some women an opportunity for an education for the first time, producing leaders like Xiang Jingyu. She was a revolutionary from a bourgeois family background who was one of the first women in China to attend school into the upper grades, where she became radicalized as a student. She rejected an arranged marriage and her family’s class privilege, and integrated with the masses by working in a silk factory. She led ten thousand women factory workers in a strike, and founded the Committee of Women’s Liberation to train young women cadre. Xiang shaped the foundations of the women’s movement with her sharp analysis of the conditions of women’s lives in her report Resolution about the Women’s Movement,which was adopted by the 3rd National Congress of the CCP in 1923. Her report drew an anti-imperialist dividing line against Christian missionary reforms (seen by many at the time to represent the most progressive attitude toward changing conditions for women and children).

In 1928, Xiang Jingyu was executed by the Guomindang, the Nationalist government that initially allied with the CCP but betrayed them in 1927, as part of the anti-communist counterrevolutionary purge known as the White Terror. She was 32 years old.

Xiang Jingyu’s story is worth telling here even briefly because it illustrates how the communist movement came right out of the box inspiring and mobilizing women to achieve incredible transformation as revolutionaries, and make huge sacrifices. Women did not just passively accept reforms, nor was the oppression of women treated as a niche concern. As the Communist-led Red Army moved through China, they brought their mandate of women’s liberation into the rural areas where peasant women may not have even heard of the May Fourth movement, but simmered with righteous rage at the oppressive conditions of their lives, ready to boil over.

The Red Army, the first army in China’s history to enlist women soldiers, distinguished itself as a communist army from the beginning through its interactions with the masses, carrying out patient political work to win them over to join or support the revolution and holding itself to much higher ethical standards than any bourgeois army ever has. In contrast to the terror meted out to women in particular by soldiers throughout world history (including the brutal legacy of US occupations and military bases), in the Red Army, rape and abuse by soldiers was punishable by death.

Women in the Red Army talked with peasant women about their lives and led them in forming Women’s Associations, where they would back women in confronting landlords and abusive husbands, fathers, and in-laws. The Women’s Associations mobilized public struggle with abusers in “speaking bitterness” meetings, and often administered revolutionary justice against abusers and oppressors of women in the form of beatings. In the book China Shakes the World,journalist Jack Belden described the story of a young woman he refers to as Gold Flower, who is approached by the Women’s Association of the 8th Route Army (the Red Army’s main fighting force) and offered support confronting her rapist husband. It’s a striking example not only because Gold Flower is empowered by revolutionary women and her life improves, but because it shows how this process of “turning over,” or transforming into a revolutionary who will not accept the feudal status quo, brought the masses of women into political life.

The “speaking bitterness” sessions and the formation of Women’s Associations trained women to run political meetings lively with mass participation, conduct social investigations to understand what women were facing, and mobilize struggle against specific features of women’s oppression. Women who joined the revolution spoke in public rather than staying shut up at home, confronted the most threatening people in their daily lives, relied on and took strength from being part of a collective of comrades, and won over their families and neighbors to join the revolution. The Red Army’s cultural troupes spoke to the heart of peasant women’s lives with inspiring musical and theatrical performances, and their educational teams taught people to read and write who thought they would die illiterate. Women were not only included in all of this but were integral to the entire process, brought into public and political life, and trained in struggle.

Building a New Society

When the Chinese Revolution came to victory in 1949, women communists held positions of government leadership from the beginning of the new socialist government, including as Minister of Justice and Minister for Public Health. The All-China Women’s Federation was created to prioritize the ongoing struggle for women’s liberation, mount mass campaigns, and put collective, centralized, political power behind the Women’s Associations created during the Revolution. Dramatic legal changes were made to the status of women, most notably the Marriage Law of 1950, which acted on the Chinese Communist Party’s critique of how important the old society’s traditional marriage system was to upholding patriarchal and feudal structures. The 1950 Marriage Law abolished forced marriage and child marriage, ended the buying and selling of brides, gave women the right to divorce, and overall ended the legal subordination of women under men.

The Marriage Law sent shock waves through China’s traditional social order. At the same time that land reform was taking effect and landlords were being stripped of their property, they were also being stripped of their social standing and their right to concubines. As peasant women realized that they now had the freedom and support to dissolve abusive marriages, peasant husbands, who knew that in the feudal order, their wife had been the only person below them in the social hierarchy, often did not accept the law. It was not easy to enforce, and when the Women’s Federation reported that hundreds of men had murdered their wives rather than accept a divorce, some CCP cadre wavered, and even suggested that the state should ease up on enforcing the law. But a mass education and propaganda campaign popularized the Marriage Law, engaged women in asserting their rights, and involved local women’s committees along with state power in making sure that women’s equality was enforced.

Another big change the communist-led government was able to implement right away was the end of the sex trade. Brothels, which had been numerous in big cities like Shanghai, were shut down, and the Women’s Federation arranged for those who had been sex workers to get medical care, get housing for themselves and their families, and take part in the opportunities for meaningful work that were opening up for women all over China in the new society. Mass education campaigns taught people to understand prostitution as one of the harshest forms of women’s oppression, and that sex workers, rather than being morally deficient or “ruined,” are brutally exploited victims of patriarchal oppression who have every woman’s ability to join the revolution and seize their own liberation.

Women who had been empowered to transform their lives and the social fabric of their communities during the Revolution threw themselves into production roles, in factories as well as agriculture, and in education and healthcare fields. Of course peasant women already knew they were capable of incredible feats of labor; they had to juggle housework, childcare, and farmwork on a 24-hour schedule. But in the new socialist society, for the first time, their labor was not invisible but celebrated. In the years after the revolution, agricultural work was emphasized to feed China’s laborers as they worked harder than ever to modernize industrial production and raise the standard of living for the masses. Women’s agricultural work teams astounded the country with their rate of production, physical strength, and dedication to feeding China. In the 1960s, these farm workers became known as “Iron Women” and were praised as a model of what a woman could achieve: destroying old myths about women being physically inferior to men, able to harness the interdependent power of a collective, and driven by their understanding that their labor was connected to their love for the people, not personal gain.

Whereas before the Revolution women and children’s lives had been stalked by extremely high rates of maternal and infant mortality (so much so that the average Chinese woman’s life expectancy was 30‒40 years), ten years after the Revolution, maternal mortality had dropped by 98%. Healthcare teams gave traditional midwives, whose knowledge and experience was respected, basic training in germ theory, and gave them free sterile medical equipment and access to a more thorough education. Far-flung rural areas got access to modern medicines as well as traditional Chinese holistic medicine. The Women’s Federation organized teams to go door-to-door and speak with women about infant care and, when a safe and effective birth control pill was available, family planning, and register them with social services and nutritional support. In 1953, abortion was finally legalized and deaths from self-inflicted and amateur abortions ceased.

Childcare collectives were established starting in the early 1950s so that women could work and generally get out into public life, first in the cities (near work sites, so women could be near their kids and check on them through the day), and then, with the start of agricultural communes, in the countryside. Childcare workers got training in childhood development and education, and elderly women with experience caring for kids supervised young women, and told children stories about their own personal histories and what life had been like before the Revolution. The childcare collectives freed up women to work and experience the world outside the home, making raising the next generation truly a mass effort, and taught children from a young age to live collectively. They profoundly shook up the patriarchal social order by undermining the model of the nuclear family.

None of these major steps meant that women’s oppression in China was over. Centuries of oppression and patriarchal conditioning of both men and women had to be struggled over, uprooted, transformed, and struggled over again, in every corner of the country. But in the decade after the Revolution’s victory, the entire landscape of women’s conditions was transformed, and it happened fast. None of these changes could have been made by the work of Women’s Associations alone without the power of the state in the hands of the masses. And they had to be made, decisively, for Chinese women to step into their place as fellow architects of a new, liberated society.

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution

Yes, I had changed. I discarded the vanity and sense of superiority typical of city folks and became more down to earth. My life in the countryside changed my way of looking at the world and at life. Even today, my love for crops and other plants, my respect for and easy bonding with physical laborers, and my cherish of grain and other foods have their roots in the time I spent in the countryside.

– Naihua Zhang on her experience as a “sent-down youth,” as recorded in the anthology of personal history Some of Us: Chinese Women Growing Up the the Mao Era

When Mao Zedong, the leader of the CCP, initiated the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (GPCR) in 1966, he urged the masses, especially young people, to interrogate ways that old reactionary traditions were still pervasive or had taken different forms after socialism was established. Drawing the whole Chinese population into criticizing Confucianism was a key aspect of the GPCR, and it was extremely mobilizing for women, as it got at the roots of the most pervasive forms of their oppression. This was the period where Mao advanced the famous slogans “women hold up half the sky,” and “women can do anything a man can do,” defining women as equal makers of revolution and challenging Chinese society broadly to fully incorporate women into every aspect of work, culture, and political struggle.

An important aspect of the GPCR was that urban youth, who tended to be more educated and privileged than rural youth, were systematically “sent down” to the countryside to live and work alongside the peasants and learn from them. It was a life-changing experience for millions of young people, but especially for urban women, who got to see, more starkly, the ways that people were still caught in traditional, feudal social relationships. At the same time, they also got to see how much effort the rural people put into creating a new society by feeding it, and how, in fact, the peasants got their pride and their drive from their political education and knowing they were contributing to a communist future. The youth got to see what the life of a real “Iron Woman” was like, and learn from their discipline and strength. Some got to put their educations to use as primary school teachers and as “barefoot doctors,” youth with basic medical training who worked alongside their patients in order for basic healthcare and public health education to finally penetrate into China’s vast rural interior.

Women were active in the student-led militant social movement known as the Red Guards and in the revolts in schools, often distinguishing themselves as fiercer in their critiques and condemnations than men (and in many cases, just as violent and excessive; women could absolutely also be bad actors on the grim side of the GPCR). Young women vehemently rejected stereotypical gender roles and gender expression, often opting for short or simply braided hair and unisex work clothes to emphasize their lack of concern for fulfilling traditional beauty standards.

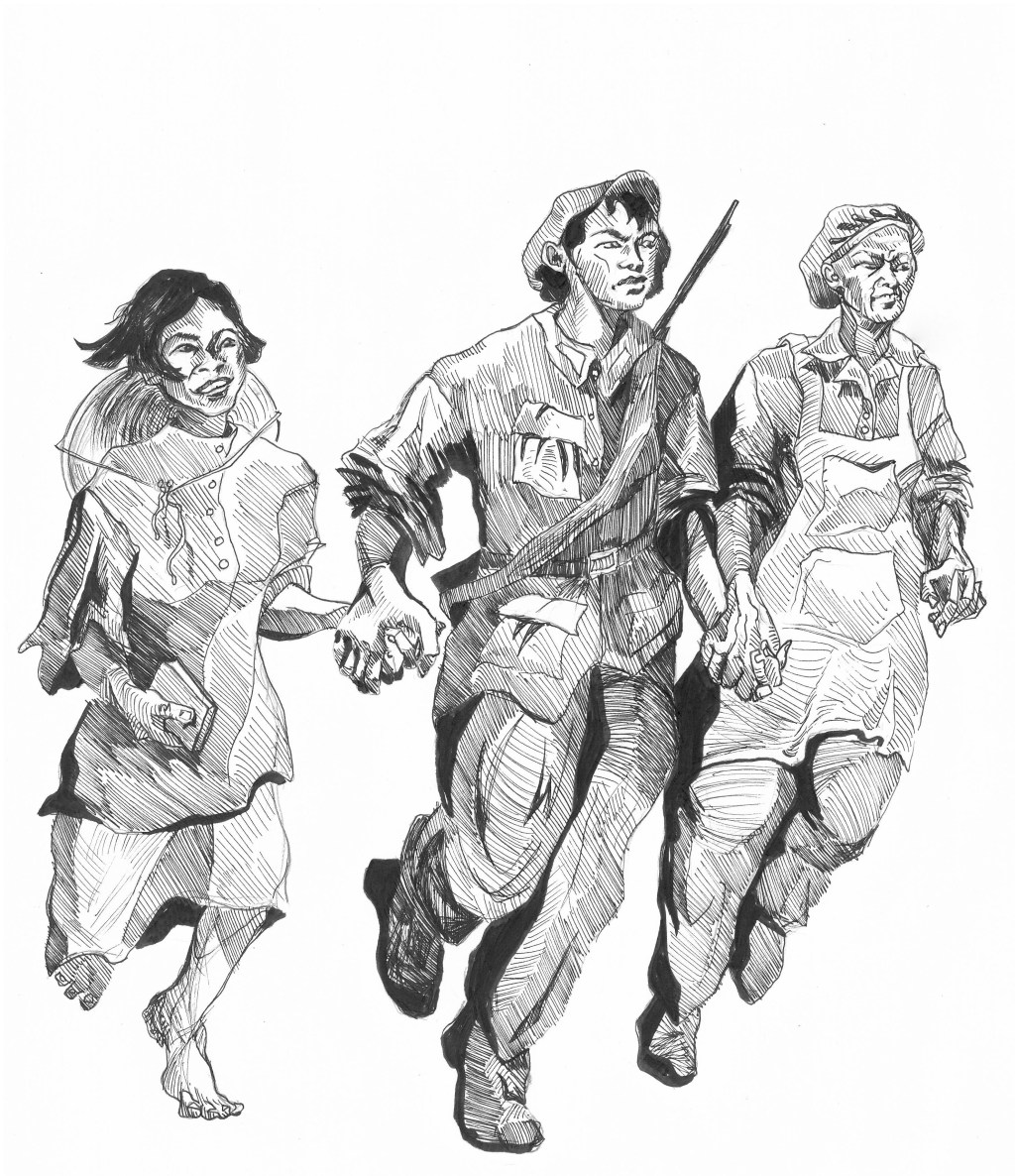

During the GPCR, a series of “model works” in the form of operas, ballets, and musical compositions put revolutionary politics and history on stage and showed the masses, including women, as the makers of history. Among the model works was the ballet The Red Detachment of Women, politically directed by Jiang Qing (Mao’s wife, and a communist leader in her own right, who made decisive political and artistic contributions to the GPCR). The Red Detachment of Women opens with the depiction of a young woman, Wu Qinghua, held as a slave by a landlord in the old feudal China. After breaking free, Wu Qinghua joins up with a brigade of women soldiers of the Red Army. While she joins the Revolution with the motivation to get revenge on her oppressor, the landlord who held her captive, she transforms into a fighter for the liberation of all women and all oppressed people, playing a heroic role in battle within a collective strategy. Besides The Red Detachment of Women, other model works of the GPCR, such as the operas The Red Lantern and Azalea Mountain, portrayed women in heroic roles, stepping up to the forefront of the revolutionary struggle and overcoming challenges by men to do so. And the women who starred in the GPCR’s model works were some of the most badass singers and dancers of the 1960s and 70s in the world—badass revolutionary artists, not sexualized icons.

Anti-communist criticisms of the women’s empowerment aspect of the GPCR focus on the supposed “masculinization of women,” as though throwing off traditional femininity and youth being able to try out different forms of gender- and self-expression were a kind of repression. Another complaint from Western feminists regarding the GPCR is that “women’s issues” were not given enough attention because they were not treated as separate from the full fabric of the revolution, or that in proclaiming that “women can do anything a man can do,” the communists were “erasing female identity.” These criticisms are noteworthy in that they accidentally illuminate how (1) in revolutionary China women were not trying to commodify their gender expression or present themselves as women first and revolutionaries second, (2) women were equal actors in making revolution, not receptacles for the decisions of male cadre, and (3) it is a positive and groundbreaking shift in thinking about women’s oppression and liberation to proclaim the simple fact that women are 50% of all humanity—holding up half the sky—and that therefore our “issues” run throughout every possible aspect of human experience.

Today, women around the world no longer have a revolutionary China, but we have a guide to our liberation

In 1976, after the death of Mao, counterrevolutionaries seized power in China, putting the country back onto the capitalist road. The devaluation of women began immediately, if with different characteristics than under feudalism. Many revolutionary women leaders were stripped of power. Jiang Qing, who played an important role in the GPCR and fought defiantly against taking the capitalist road, was persecuted, imprisoned, and demonized. There was a backlash against freedom of gender expression, with women who had been free to define themselves as strong and capable human beings facing social pressure to conform to imperialist standards of femininity. Today, prostitution is once again widespread in China, and state capitalist interests play a sinister role in international sex trafficking. Sex-selective abortion, where a decision to terminate a pregnancy is based on the sex of the fetus, is common.

But the counterrevolution can’t erase all that was achieved for women’s liberation during China’s socialist years. So what can we take forward into the future, as people who hate patriarchal oppression, who look at the example of the Chinese Revolution and see that we don’t have to live under patriarchy?

Chinese women fought for and largely won their liberation by becoming revolutionaries, by throwing themselves into struggle. Since Mao summed up for us, in word and deed, that women “hold up half the sky,” we know we can’t separate women’s oppression from the entire package of capitalist-imperialist rule. Today, features of women’s oppression like domestic and sexual violence, forced childbirth, and grueling lives of multiple minimum-wage jobs and having to raise kids, clean, and cook seem inescapable. But the Chinese Revolution definitively showed the world how strikingly women’s lives can be transformed—if we overthrow capitalism-imperialism. Even the 1976 counterrevolutionary turn in China could not erase all the progress the women’s movement made, and even strident anti-communists and bourgeois institutions like the World Health Organization have had to grudgingly admit that the lives of Chinese women were overwhelmingly improved in the course of the revolution.

The historical example of the Chinese Revolution also challenges us to not waste our time struggling for reforms within the present system, or content ourselves with even legitimate improvements, but to uproot the entire social order, to create an entirely new way of life. To seize on the realities of women’s lives not to narrow the scope of our vision, but to use as rage-fuel propelling us into our righteous place as the makers of history. To shape a world where our daughters (biologically and spiritually) can have not just the sharp edges taken off of their oppression as women, but actually transcend the shallowness of the roles capitalism lays out for us and step into the sun.