A social investigation of Lorain, Ohio submitted by GATT readers in the Midwest, October 2025

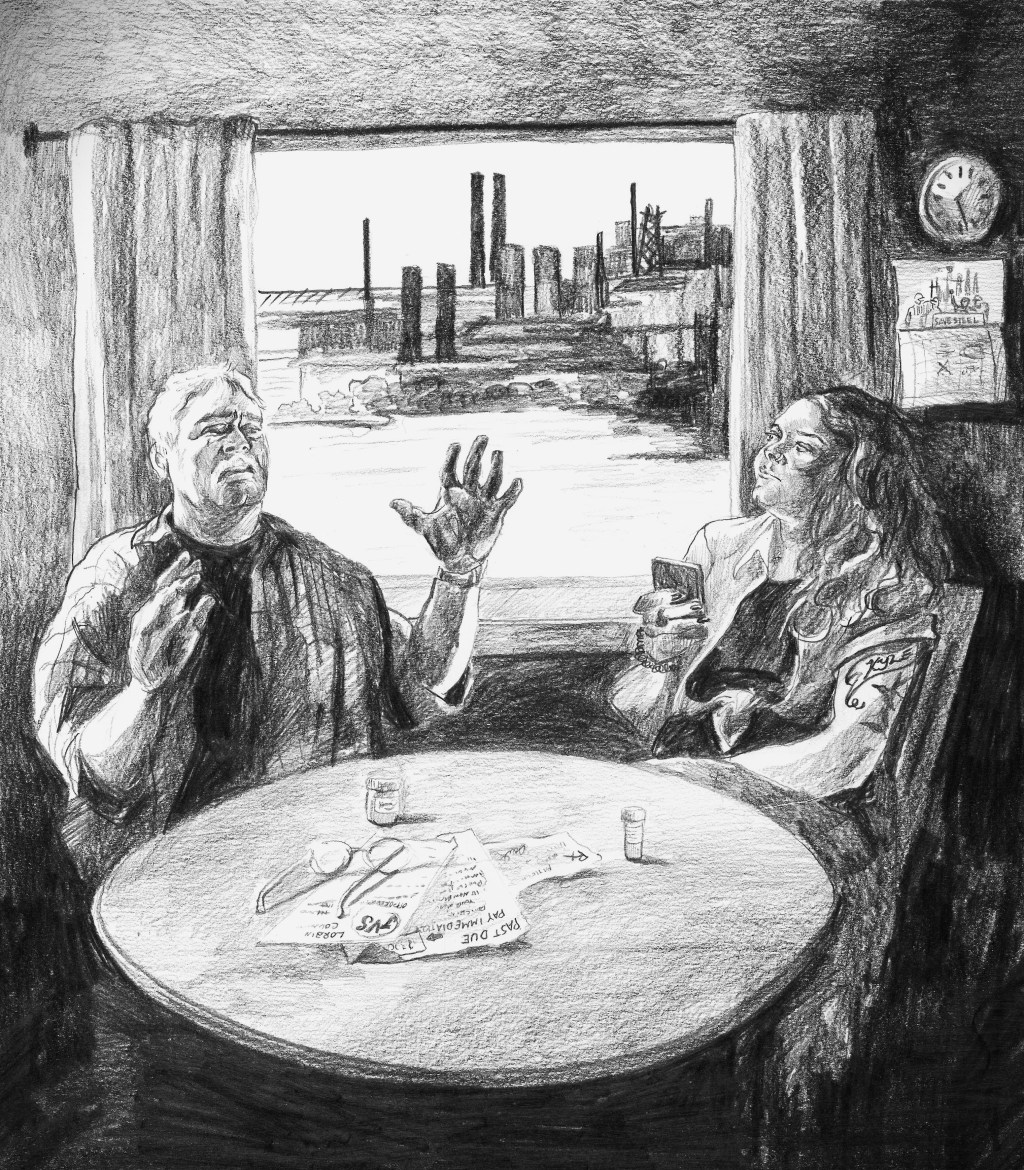

Chris is 68 years old and started working at a steel mill in Lorain, Ohio when he was 18. He always knew he’d be able to find a job in manufacturing; in the early 1970s, you could get fired from one plant in the morning, walk to another job site, and get hired again by the afternoon. By the 1980s, he was working at the Ford auto plant when a series of layoffs left many workers, including Chris, economically stranded for the first time in their lives. Chris became a house painter, a job he worked for the next 26 years. In the course of his career, Chris developed chronic pain in his neck, back, and knees; in the early 2000s, he was prescribed Oxycontin to cope. The pain pills got too expensive and doctors became hesitant to prescribe them, so Chris turned to heroin and remained in thrall to addiction until just four years ago. He’s seen his daughter die of a fentanyl overdose. When asked about the future of Lorain, he says he doesn’t believe industry will ever return and that the future is “tumbleweeds.”

We spoke to Chris outside a gas station near Lorain’s largely abandoned main drag, Broadway, as part of a social investigation into the dispossessed, formerly well-paid working class of the deindustrialized “rust belt.” We spoke to dozens of people of different walks of life who talked about their hopes or despair for their youth and the future, deindustrialization and how it delivered people into the jaws of the opioid crisis, the fraying social fabric of a formerly tight-knit community, and, over and over, their pride in Lorain as an “international city” of diverse, hardworking people. Chris’s story was echoed in the stories of many people we talked to who are disillusioned by the current system and particularly electoral politics, isolated from their neighbors, and economically trapped in a place that feels like home but offers no viable way of life.

A rust belt city with international pride

Lorain County, Ohio burst onto the world stage in the early 20th century as a magnet for people from all over the country and the globe seeking employment in the shipyards, steel mill, auto factories, manufacturing plants, and all the service industries hustling to meet the needs of the heavy industry workers. A geographically large, sprawling county with a few small cities (the largest is also called Lorain), many small towns, and a huge rural interior, and bordered by Lake Erie to the north, Lorain County remains ethnically diverse. Especially in Lorain (the city), there are large minorities of Black and Puerto Rican people, and many among the white majority have strong connections to Eastern European, Italian, and Irish heritage, with social establishments like “The Croatian Club.”

Starting in the 1970s, deindustrialization hit Lorain in waves, with major employers shutting down operations and moving away to get cheaper labor in countries dominated by US imperialism or even as close as Appalachia. The steel industry in particular always had boom and bust periods, so workers initially assumed layoffs would be temporary, and many said it took a while for the new reality to set in until the Republic Steel mill shut down. There’s still manufacturing jobs to be had, especially if you are able to drive to far-flung parts of the county, but it’s seldom stable employment and rarely well-paid (the state minimum wage is $10.70/hour, with many employers able to get away with the federal rate of $7.25/hour). More people work in struggling service industry jobs and lower-tier healthcare (there are several hospital systems in the greater Cleveland area).

From the 1990s through the 2010s, Purdue Pharma aggressively marketed its signature painkiller drug, Oxycontin, to economically devastated areas in the rust belt and Appalachia with high rates of workplace injuries and chronic illness, leading to an explosion of opioid addiction and overdose deaths in Lorain County. 27% of people in Lorain live under the poverty line now, and the city has a remarkably high rate of violent crime for its size.

Though historically strongly aligned with trade unions and the Democratic Party, in 2016—for the first time in history, and the same year that the steel mill shut down for good—Lorain County voted for the Republican in a presidential election. Our social investigation crew wanted to find out why Donald Trump appealed to a historically Democratic, ethnically diverse city of immigrants, how people saw the potential future of their city, and what they thought it would take to change their conditions.

The abandoned Republic Steel mill industrial complex, which covers 435 acres of rotting infrastructure and leaking toxic waste, looms over 28th Street. But right across the street from the old mill, on an early Fall Saturday, the Puerto Rican cultural center, El Centro, was hosting a “community resource fair” and classic car show to celebrate the unveiling of a mural of the Puerto Rican flag. Lorain has a longstanding Puerto Rican community, and we initially talked with a couple recent migrants who came to Lorain after Hurricane Maria and, in contrast to more longtime residents we spoke with later, said they’d never leave Lorain (“hell no, I make $19/hour here!”). They explained that even if wages are lower than in major US cities, access to jobs and the relatively low cost of living make staying in Lorain preferable to living in post-Maria Puerto Rico.

A couple of friends at the car show, Alan (a Puerto Rican man in his thirties) and Gene (a Black man in his sixties) told us they met in prison and that one of the great things about Lorain is the sense of community and “integration.” They both realize that there’s not a lot of places in semi-rural Ohio where people of different nationalities can mix it up. Another pair of friends at the car show, a Black man and a white man both in their sixties, who we talked to separately, echoed this sentiment. They attributed friendships and social integration across nationality lines to decades of working side by side at hard physical labor, with people from all over the world and the country, in the steel mill and auto plants (describing, though they didn’t use the word, proletarian collective discipline). They said that back in the day, there were bustling bars and clubs all up and down Broadway and 28th St., but now it’s a ghost town.

All these guys talked about a rise in violent crime, particularly related to drugs, and said that this is directly tied to a lack of well-paid jobs these days. Gene and Alan noted that there’s a lot of competition for the manufacturing jobs that remain, and that some job sites offer private bus transportation, which makes them even more sought after as the public transit system has been completely gutted. There are now just two bus routes that run through Lorain, and they run irregularly, making it impossible to get around the city, let alone to outlying rural areas where most of the existing manufacturing jobs are now, if you can’t afford a car.

Fentanyl, the future, and revolution

We caught up with Gene later and he told us more about his life. He grew up partly in Lorain with one parent and partly in Illinois with another, and got into violent crime (robbing, pimping, dealing) as a young man. He traveled all over the country and was in and out of prison for about 30 years. When he returned to Lorain 15 years ago, he was struck by the lack of racial segregation compared to places like Chicago, and by how the jobs that sustained families in his youth were all gone, leading people to deal drugs to get by and use drugs to cope with everyday despair. Gene emphasized the impact of fentanyl1 on Lorain, noting that for a while in the 2010s, this county had the third highest rate of overdose deaths in the US.

Gene was one of many people we talked to who expressed a lot of fear for the future of the next generation. He has two adult children, one of whom was murdered last year. He said schools are failing to teach kids to be free thinkers; they teach kids to be employees, but they don’t actually offer vocational skills, and once high school students graduate, their only real option is to work in fast food. To make about $20‒$30k per year, he said, you have to leave town, and because of this, kids just turn to the streets. We asked him what it would take to change things and he replied that on a national scale, “the Left wing and the Right wing are all on the same bird, so they’re going to do whatever benefits them.” He added that people who refuse to take a stand are part of the problem, whereas “I don’t want to sound like George Jackson or Fred Hampton, but I think there needs to be a coup. Doesn’t have to be a violent revolution, but there needs to be some fresh, upcoming new minds that are running for the people.”

Many people we spoke with in Lorain talked about a lack of faith in either political party and politicians in general, but Gene was one of a few people who referenced the need for a total uprooting of the system. Most people referenced a need to bring back industry, turn to Jesus, and/or have stricter attitudes about raising their kids. Gene said that he was exposed to revolutionary politics through the Nation of Islam while in prison. Trey, a young Puerto Rican father and mechanic who we talked to later in the park, was another person who expressed an understanding of systemic oppression and a lot of anger toward the ruling class, saying “even a regular job is like, modern day slavery, it’s like, you’re gonna lay this concrete while we run off with all the millions… They fear being overthrown, but it’s crazy to think, we outnumber them. If the 99% stood up to the 1% they wouldn’t stand a chance.” Trey made similar remarks about imperialism: “that’s what they do, come in with their guns and a million-man army to overthrow, colonize, and profit off the labor of the people,”and that there should be a revolution, and people need to be willing to die for change. But when we talked with him about different activist organizations and offered to get him involved in some way, he backtracked, saying that he just needs to focus on raising his daughter and that the real problem is “handouts for people who don’t support the economy.”

“Nobody’s making enough to survive in Lorain”

Across town, we talked to people in the parking lot of Fligner’s grocery store. A Black woman in her forties shopping with her teenage daughter told us that she’s a nurse and that healthcare is one of the only stable, salaried jobs in the area. With obvious pride in her daughter, she spoke on how “early college programs” that allow high school students to graduate already holding an associate’s degree are really popular, but also encourage the best and most driven students to leave the area as soon as possible. She seemed very civic-minded and said that what Lorain needs is for young people to have more of a stake in their town, and she tries to get teenagers together to attend town hall-style meetings on local social issues at the high school. But these meetings, like a recent one about the used needles and other hazards around the homeless shelter on 28th St., devolve into “a mess” where everyone talks over each other. She and her daughter agreed that people are more divided than ever since the COVID pandemic, and it’s hard for people to come together even on issues that affect them all.

Another young Black healthcare worker, a medical assistant in her twenties, told us, without hesitation, that the worst problem in Ohio was the minimum wage. She said she worked 80 hours per week and still couldn’t afford to leave even though she’d love to, and that “nobody’s making enough to survive in Lorain.” Later on, we talked to Greg, a young Black man living in a homeless shelter as he worked two fast food jobs and commuted to school. We talked to many people who described grueling work schedules for incredibly low pay, who stated over and over that even though it’s hard to get by, the cost of living in Lorain County is so much lower than more prosperous cities like Cleveland that they can’t afford to leave.

The current construction boom in Lorain means that a few manual laborers have unstable seasonal employment. Hunting and fishing is both a popular recreational activity and a way for seasonal laborers to make ends meet. We talked to some fishermen who explained that even this hustle is becoming difficult because of over-fishing by large Canadian companies.

“A house divided”

When we carried out this social investigation, fascist podcaster Charlie Kirk had just recently been publicly shot to death. Many people mentioned how disturbing they thought the shooting was, or used it to describe the political climate in the US as volatile and scary. Some people hadn’t heard of Kirk before and were under the impression he was killed for his Christian beliefs. Others felt like he got his comeuppance, like an older retired auto worker who told us “he died by the sword he lived by, and nobody’s lowering the flag to half mast for all the little kids getting shot in their schools.” He followed that up with “I bet you were gonna stereotype me as an old, bald white man who would say something different!” before riding off into the sunset on his motorcycle with a wink—reminding us to keep an open mind when talking to people!

People cited the Kirk shooting before saying they didn’t want to talk about politics, and in fact, we did notice a significant lack of political flair, like signage, in Lorain, although you see plenty of campaign signs, rainbow flags, etc. when you get closer to Cleveland. People were more likely to cite cynicism with both political parties and with politicians in general than cheerlead for one or another. There was an overall sense that anything directly political was a socially sensitive topic. Many people would say something to the effect of “look at what political division in this country has come to, murdering people in broad daylight even if he was a horrible person, so it’s better not to discuss politics” before discussing their political views and framing them more in terms of personal values and social responsibility.

One exception was Christy, a 44-year-old mom and school administrative assistant, who spoke to us at her home in a relatively affluent subdivision. She told us that while she had voted Democratic all her life, her husband had voted for Trump in the last few elections. She described their family as “a house divided” and said she knows a lot of couples in the same boat, where the wife votes Democratic and the husband votes Republican. Christy, who is white and grew up in Lorain, emphasized that she’s extremely proud of Lorain’s diversity and “international character.” Besides family being nearby, that’s the main reason she wants her kids to grow up there despite the lack of job opportunities and deterioration of the schools. She felt betrayed that her husband voted for someone who rallies against immigrants and other oppressed people, but chalked it up to her belief that overall men are more “practical” and women are more “compassionate and nurturing.” Christy said that her husband is a proud, blue-collar guy (he works at one of the manufacturing plants in a neighboring municipality), and many people like him were attracted to Trump’s promises of bringing back industrial jobs and a lost way of life to “blue-collar people.”

Christy tied this “practicality” of voting for Trump and the “blue-collar” identity to a distaste for “asking for handouts” (government aid in general), and to an unwillingness to “ask for help,” i.e., seek mental health care or assistance in addressing substance abuse—or even admit that they receive, or have family members who receive, government aid or treatment for addiction. Her description reflected the “bootstraps mentality” we heard from a few other people, like a charter school principal whose school runs a vocational program that allows young people to “skip the fluff” (the arts and humanities) and get straight to work, and from several religious people who dedicate significant time to charitable work in their churches but think issues like homelessness, addiction, and mental health are individual problems caused by personal flaws.

The kids are cooked

Christy has worked with high school students for most of her career and she worries about “her kids.” She sees them slip into addiction and lives of crime and it breaks her heart. She remembers when there were four high schools in Lorain; over time, with the population dwindling, they closed three down and now there’s only one high school. She said there are few social outlets for young people; even school team sports are few and far between, and she recently took on a weekend job to pay for her kids to play club sports. The YMCA shut down. The county community college and vocational school fast-track kids into college programs which gives them something to do, but also feeds into what Christy termed “bright flight,” where the most ambitious young people leave and never come back. The teenagers who don’t manage to leave are “gaslit” by the adults around them telling them to “Get a damn job! But where? Everything is closed!” Christy had a lot of sympathy for Lorain’s youth, but many other older adults ragged on young people as being lazy, always on their phones, and hooked on “pharmaceuticals” (even while also describing how easy it was to get a well-paid job in walking distance back in the 1970s). Any benefit from a lower cost of living in Lorain is countered by the situation that austerity and the economic hollowing out of the city has created: the lack of social services, recreation, or even transit.

We didn’t meet any visibly or vocally LGBT people during our weekend in Lorain, but one woman outside Fligners grocery store mentioned, unprompted, that although Lorain is generally friendly she doesn’t think it’s safe for “people who are different,” by which she said she meant gay and transgender people. Tania, an evangelical Christian in her fifties who we spoke with outside another grocery store, talked about kids wanting to “change genders” being a big social problem in her eyes, and tied that to youth not having respect for their elders or parents, who were often “being their kid’s friend and not their parent.”

We attended Sunday service at a liberal Protestant church in Elyria, the county seat, with a small congregation of elderly white people, who were extremely excited to have a visiting group of younger people. They gave us a tour of their beautiful, and mostly empty, building, which includes classrooms and nurseries, although we didn’t see any kids. A few people told us about their childhoods and how youth these days aren’t able to take the bus to hang out with their friends, let alone have the vibrant public spaces they remember fondly. Their parents moved to Lorain for industrial jobs, and were able to transfer a middle-class lifestyle to their children, but the church people understood that’s not accessible for today’s youth anymore. They gave us each a gift bag which included a rainbow postcard proclaiming that “God says all of THEIR creation is FABULOUS—who are we to disagree?”

“No one is ever just homeless to them”

Christy told us that the police don’t even bother to patrol her neighborhood, and that everyone knew they had to focus on the “Dirty 30” (streets numbered in the 30s), which has all the section 8 housing. She also felt that racial profiling is not as much of a problem in Lorain as it is in other parts of the county or in Cleveland. That echoed what other people told us about racial tensions being less pronounced in Lorain, but we heard from many other people, especially homeless men, about police harassment and open racial profiling. Greg said of the cops, “No one is ever just homeless to them, you’re always up to something.” When we spoke to people hanging out around the public library, we did see the cops pull up to arrest some homeless guys.

At El Centro, a Black woman United Way staffer told us there’s been an increase recently in different oppressed groups blaming each other for social issues facing them and tensions rising there. We also heard from a few different people that closing three high schools led to violent conflict when kids from racially segregated social groups had to attend school together.

Several people also told us about a recent shooting where three cops sitting in a squad car eating lunch were ambushed; two of the cops died, as well as the alleged shooter. Christy framed the killing as an anti-police crime, i.e., that they were targeted for being cops; other people told us the alleged shooter had a long history of serious mental illness, including being institutionalized. Some of the only political signage we saw was in Christy’s neighborhood, where a few of her neighbors had yard signs about supporting the police. However, more people we spoke with listed, when asked about major problems in Lorain, the issue of police brutality.

Homeless and surrounded by boarded-up homes

In her current job working for a neighboring school district, Christy works with homeless public school students, and says that this fall she’s had more families register as homeless than ever before. Several other people, particularly moms we talked with, pointed out homelessness as a major issue in Lorain. We spoke with several homeless men by the public library and outside a Catholic Charities shelter on 28th St., who talked about being treated badly by the shelter, strung along as they tried to find permanent housing and thrown out for small infractions.

Jesus, a young Puerto Rican man, moved to Lorain for a job opportunity and became both homeless and stranded when it fell through. With a registered firearm but no home, the only place he could store his gun was in his car, and when police pulled him over for speeding, the encounter ended with a fourth degree felony charge, a two week stay in county jail, and the loss of his now impounded car. Jesus had no prior criminal record, but now he’s trapped in a downward spiral where he can’t find a job or decent housing because of his arrest. He viewed his situation as being part of a larger system of injustice and emphasized what a punitive effect having a criminal record can have on people who are just trying to get by.

John, a 57-year-old white man, is from Lorain and moved to Arizona for the kind of manufacturing job no longer readily available in his hometown. In Arizona, he and his coworkers watched as a new factory was constructed within their line of sight across the border in Mexico. When it was completed, his employer announced that the US factory was closing but that they had the option of continuing to work at the factory in Mexico, for $8/hour (compared to $12/hour in the Arizona factory) and $175 in visa and passport fees. Without us asking about trade agreements, he volunteered that “NAFTA is the biggest mistake we ever made.” (Most former industrial workers we talked to didn’t mention NAFTA by name, but did refer to “foreign steel.”) John held out hope for industry to return to Lorain, speculating that the tariffs on foreign goods proposed by the Trump administration have loopholes that would allow foreign companies to manufacture goods in the US.

Another white man in his fifties, David, is a recovering addict, and explained that he’s a professional union worker with 20 years of experience in carpentry and other skilled trades, but that employers don’t like it when you apply and list a homeless shelter as your address. David thought that too many resources are going toward “illegals” but followed that up with “anyone should be able to move here.” It was interesting to hear classic MAGA talking points mixed in with the “international city” ethic.

Greg, the young homeless man mentioned earlier who works two fast food jobs, had a more systemic view of homelessness: “There’s hella empty houses in Lorain… If you go online, there’s a bunch of houses listed for rent, just sitting.” He emphasized that there’s no public transportation to better social services or decent jobs, which have relocated to more remote parts of the county where you’d need a car to get there. “You claim there isn’t enough housing yet there’s all these abandoned houses. They still get their check so they don’t really care about addressing homelessness. It’s like they want you to be homeless, the shelter makes money off you regardless.”

David also spoke to how he feels the city would rather throw all the homeless people in jail than address any of the root causes of it, and that it’s hard to “revitalize” an area with a shelter in it, so the city wants to keep all the shelters, low income housing, and social services in one segregated area. We talked to the owner of Key Foods, a Puerto Rican grocery store (he says a businessman has to find his niche) who said that the city leaders keep promising to bring industry back “but they just build more homeless shelters.” It would seem that even as it’s no longer profitable to exploit people in Lorain as industrial workers, the nonprofit industry is finding a way to profit off misery in Lorain. Many of the homeless guys referred to the recent passing of anti-vagrancy laws in Lorain, which specifically criminalize sleeping on the street, as proof that the city is trying to corral and dispose of them rather than help off the street.

“Revitalization” for who?

The mayor of Lorain, Jack Bradley, would have you believe that Lorain is in the process of being “revitalized” with a newly landscaped waterfront, some efforts to give the downtown area some cosmetic improvements, and public events like musical festivals. We heard a few times that there’s a construction boom right now, offering some seasonal work. Eerily, when driving along the lakefront, there are certain places where you can see the carcass of the steel mill peeking over a sea of brand new houses. But Greg sees it another way: “I see they’re trying to remake downtown, for a certain group. But all of Lorain, they don’t really care about them. They try to keep the people with money away from the stuff they don’t like to see, like the homeless.”

Proponents of revitalization include Silvio and Alicia, a husband and wife in their thirties, who we ran into while they were having Bloody Marys on a Sunday afternoon on Broadway with not another soul around on the mostly boarded-up street. They’re both Puerto Rican, born and raised in Lorain, and their parents worked in the steel mill and at auto plants. They left for college and came back to be small business owners. Many people we talked to hold out hope that industry will return—hope that is dashed time after time. For example, the Navy proposed to take over the old shipyards; it didn’t pan out. Small business owners Silvio and Alicia, by contrast, think the future of Lorain lies in tourism, and would rather the city continue to fix up the waterfront as a recreational area than as an industrial site.

Brandi and her husband, house flippers from North Carolina, were also very insistent on Lorain’s potential for tourism; they see low-cost lakefront property ripe for the taking. Brandi talked at length about how much she loves Lorain, but did not mention any of the issues on the minds of locals we spoke with: jobs, the future of the youth, drugs, and homelessness. When pressed, she said she knows losing industry hurt the town, but “They need to get over it!” She echoed what we came to refer to as the soft-MAGA attitude, saying she’s frustrated at how people wallow in the past rather than getting up and making something of themselves. Her vision for Lorain doesn’t include the people of Lorain, but rather a Lorain for tourists and yuppies.

There was a certain amount of automatic defensiveness in the “revitalizers” and developers we talked to, particularly a landlord couple who insisted people should be grateful to them for the part they play in cleaning up blighted areas. We can see how they may have run into hostility before: several people told us their stories of being evicted or having their landlord sell their home out from under them, casting them into section 8 housing.

The hungry ghosts of cash and addiction

Many people spoke about what we will call the spiritual component of stagnancy and desperation in Lorain. One woman passionately declared that what’s wrong with the world is that “humanity has lost sight of humanity;” the pastor of the church in Elyria we visited told us “we’re in the era of every man for himself.” A few people connected this to the COVID pandemic, saying that in the last five years nobody wants to sit around and have a beer anymore, or even talk on the phone.

Luna, 32, vividly described how a lack of connection to other people or a sense of purpose in your work gnaws away at your soul. She grew up in Oberlin, a small college town just south of Lorain, and met Dan, a fracking2 rig worker, in Michigan when she was 20. She dropped out of college to travel with him to different drill sites around Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, living in the “man camps” that house workers.

This is a job that requires hard manual labor and no college degree, and pays extremely well. But in contrast to the formerly well-paid industrial workers in Lorain who described their work fostering a tight-knight community and vibrant social life, Luna described fracking as an industry that discourages social ties and incubates crime and violence: “It attracts a personality type that’s like, these are the guys who try out the army and then get kicked out. And it’s the kind of money that these guys have never seen in their lives… And there’s a sense of, my god, what do I do with this money, and so they buy drugs, they buy sex, they’re looking for something to feel a little bit better. Because they have a very physically taxing job and also, it means nothing. There is no meaning on a day-to-day basis of, like, I’m making my neighborhood better… Dan called it ‘skull-fucking Mother Earth.’”

The relationship became abusive, and Luna eventually left and made her way back home to Oberlin, only to find that “it felt like everyone that I had graduated high school with and had stayed had developed a very serious substance abuse problem.” She started working in the service industry and reconnected with Andre, an old high school classmate who was now a machine shop factory worker. In a familiar story, he was prescribed Oxycontin for work-related chronic pain, and turned to heroin to satisfy his addiction. Luna connects Andre’s downward spiral to a greater sense of isolation and the unwillingness to seek support that Christy named earlier: “I’m thinking about all the young men in my hometown who don’t have access or the information or both to do something like therapy, or process very old and existing pain, through the body. And instead of learning tools to process that pain at all, it’s very appealing to numb it.”

Luna knew she wanted to leave Lorain County, and saved enough money to move to Cleveland and pursue her passion for dance. She notes that Andre didn’t have the same kind of social and creative outlet: “I kept thinking that if he had something that meant something to him outside of work and family, something intellectually, physically, creatively stimulating, it might not have gone that way for him, you know? …If you don’t ever go anywhere now and you don’t meet other people and you don’t have a broader worldview, I think it’s hard to look outside of yourself and attach your life to something that means more than just your existence currently.”

Luna and Andre are no longer together, but Andre is in recovery. He voted for Trump in the last election, after a lifetime of saying he’d never vote because all politicians are full of shit and he refuses to participate in their sham. Luna thinks that Andre was able to overlook MAGA’s roots in white supremacy (Andre is Black) because he sees Trump as a breath of fresh air and a problem-solver, someone who might say a lot of fucked up things but will take practical action.

The shadow of industry and the dream of the past

The steel mill, the shipyards, and the auto plants all loomed large physically over the city as well as in the stories of essentially every person we talked to, regardless of whether we directly asked about industry. People started their stories by explaining what family member came from where to work in which factory, described their memories of the past, fears of the future, and sense of identity as all tied to industry. They had strong feelings over whether industry could ever come back or if Lorain has a viable future without it.

We realized that for many people we interviewed, the “blue-collar identity” of the area was connected to a mythology of self-sufficiency, where Lorain’s prosperous past is credited to hard work alone. More than one person used the term “identity crisis” to describe the sense of desolation that comes not only from having the whole county’s economic base and higher standing of living stripped away, but also from having that sense of blue-collar identity undermined, leaving people with a sense of shame or emptiness, and the need to find someone to blame other than capitalism. They have lived through decades of the anarchic motions of capitalism ripping through their social fabric, and their neighborhoods, family structures, economic life, and hope for the future all bear the scars of the motions of capital. While the underlying causes of this devastation—imperialist plunder and the bourgeoisie’s relentless drive for profit—are obscured from the people without a communist vanguard to shine a light on it, people do have a strong sense of being left behind.

At the same time, people also find a strong sense of identity in diversity and an awareness of how Lorain’s culture and social life was a historical product of immigration. Among the “soft-MAGA” sentiments we heard about individuals needing to pull themselves up by their bootstraps, we also heard a lot of compassion for people in dire straits. People in the most precarious situations, like the homeless people we talked to, seemed to be most open-minded toward ideas about revolution and the need to overthrow the entire oppressive system.

It makes sense to us that Trump’s brash, I-don’t-care-what-you-think persona, not to mention his open pandering to formerly well-paid, white industrial workers, might appeal to people who don’t necessarily agree with his rabidly racist hardcore supporters. Many Lorain residents are willing to overlook the “distasteful” aspects of the MAGA movement in favor of the possibility of bringing industry back, and with it, a lost way of life. In line with GATT’s Fall 2024 editorial “The reactionary repudiation of a restorationist program…,” it makes sense that people who are worn out by being played for fools by the Democratic Party would either completely withdraw from political life or get seduced by the reactionary politics of the Trump administration.

However, Lorain is a county full of people in the process of being displaced and dispossessed, and the nature of capitalism-imperialism is being exposed to them in that process. In the loss of stability, the shredding of healthy social structures, and the lack of any certainty about the future, there’s an opportunity for people to embrace new visions of what the future could look like, including a revolutionary vision. One person in our crew remarked that if a handful of dedicated revolutionaries moved there, they could really shake things up. It just depends on what force is willing the seize that opportunity.

1Fentanyl is a potent, synthetic opioid that’s cheaper than heroin or Oxycontin. Fentanyl overdose has been the overwhelming cause of opioid-relate deaths in the last 20 years.

2Lorain County sits on the Marcellus Shale, a natural gas-rich porous rock layer that spreads across Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. Hydrofracturing, or “fracking,” to drill for that gas is one industry in the region that still provides high wages to a few. When gas companies first started offering to buy extractive rights, often on land owned by small farmers, in Ohio in the early 2000s, proponents claimed it would bring back the jobs that left with the steel and manufacturing industries. Fracking never filled that economic gap (though ironically, fracking equipment was the last thing to be manufactured at Republic Steel), but it’s now a significant character in rural Ohio life. Drilling for natural gas, which is notoriously bad for the local ecosystem and known to drive up local rates of violence against women, especially Indigenous women and sex workers, can only be done a few times in one place before the supply is exhausted, so workers live in traveling “man camps,” usually in remote areas.