Pat Grant, August 2025

The oppression of trans people cuts to the heart of one of the most important class antagonisms under capitalism. Patriarchy has cleaved the world’s population in two, subjecting one half of the world to economic and political disenfranchisement and the constant threat of interpersonal violence, and granting the other half a failsafe punching bag to scapegoat, abuse, and exploit to whatever degree and with whatever frequency they want. Trans people are caught in the crossfires, their lives hanging in the balance while debates over their existence stay at the center of many of the most heated social conflicts of our time. The ideological foundations of patriarchy and the operational functioning of capitalism both demand the suppression of trans people, and mass resistance to that suppression has the potential to shake those systems to the core.

What’s more, trans people are massively overrepresented in the very small communist movement in the US today. Anecdotally speaking, we’re confident that trans people have the highest per capita disposition toward revolutionary politics compared to any other demographic group in the country. Considering both the objective position of trans people in our society and the subjective orientation of trans people overall toward radical politics,1 it should be obvious to any communist worth their salt that trans people are a source of revolutionary potential. Why, then, has that potential gone untapped for so long?

Historically, the communist movement in the US and the revolutionary movement of the 1960s were often on the wrong side of the oppression of trans (and LGB) people, due to myriad weaknesses such as economism or workerism being used to justify ignoring gender oppression; organizational cultures of male chauvinism; failures to take up the fight against gender oppression beyond bourgeois-democratic rights for cisgender women, if even that; and even outright revanchist formal lines. The second communist vanguard in the US, the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP), was, for over two decades, one of the most egregious examples of communists falling on the wrong side of this question, as evident in the 1981 RCP Programme and the 1988 essay “On the Question of Homosexuality and the Emancipation of Women” in the RCP’s journal Revolution. These RCP documents were formally in effect until 2001, and are chock full of reactionary bangers such as:

- “Once the proletariat is in power… education will be conducted throughout society on the ideology behind homosexuality and its material roots in exploiting society, and struggle will be waged to eliminate it and reform homosexuals” (New Programme 77).

- “The [1981] party Programme… correctly identifies the decay of capitalism and the distorted, oppressive, woman-hating relations capitalism inherited, upholds, and thrives on as the material basis of homosexuality today” (“On the Question of Homosexuality” 41).

- “The bottom line is that homosexuality does not escape, nor reverse, the dominant, exploitative relations of society. In fact… homosexuality serves as both a reflection and a concentration of some of the worst features of the exploitative relations between men and women” (“On the Question of Homosexuality” 46–47).

- “The gay men’s communities have typically been characterized by… some extreme expressions of woman-hating and decadence…. Transvestism and displays of stereotypical “effeminate” behavior are essentially caricatures of some of the worst aspects of what being a woman in this society can be” (“On the Question of Homosexuality” 47; emphasis mine).2

That’s not to say that the communist movement, both within the US and internationally, has never chosen the right side in the fight against the oppression of LGBTQ people. There are many positive historical examples we can look to as well, and they will be discussed later on in this article. But being honest about the past failures of the communist movement is the starting point for decisively breaking with those failures and charting a new path forward. There is no map to follow because, in addition to the inconsistent engagement of communist parties with the oppression of trans people, there is a total void of good communist theory that takes up this question.3 Since a clear path forward can’t be found in our past—although we might find some clues—this article is an initial foray into theorizing the oppression of trans people from a communist perspective, and proposing some next steps for revolutionaries who see the need to take this up. Much more will need to be written, and we challenge everyone reading this to investigate this question themselves, through study, through social investigation among the masses, and through attempting to wage mass struggle against the oppression of trans people.

As the starting point in developing a communist theorization of the oppression of trans people, we will outline a brief history of gender and gender oppression, beginning with the gender systems of pre-capitalist societies, and showing the impact that the emergence of class society, the transition to capitalism, colonization, and the Catholic Church had on these gender systems; namely, the imposition by the ruling classes of male supremacy, the oppression of women, and the suppression of all other gender roles or expressions through widespread violence that reached the level of outright genocide in many cases. We will then turn to an analysis of the conditions of trans people today and their position within society, and make some proposals regarding the role trans people can and should play in class struggle and communist revolution.

This article is a challenge to all communists to take seriously the oppression of trans people as a major social antagonism within our society and dedicate themselves to fighting its expression wherever it exists. It is also a challenge to petty-bourgeois trans people who identify with the oppression of trans people and with trans revolutionary historical figures to really be about it if they’re going to claim it, to commit class suicide, and to integrate with proletarian trans people and the proletariat more broadly and fight alongside them. Lastly, and most importantly, it is a challenge to proletarian trans people to take their place at the front of the fight for communist revolution, to become leaders within the communist movement, and to commit their lives to the task of building a communist vanguard party that can overthrow the bourgeoisie and establish a dictatorship of the proletariat. The only way to decisively end not only the oppression of trans people, but all oppression, is the abolition of class society that can only be acheived by way of communist revolution. After centuries of repression at the hands of the ruling class, we deserve nothing less.

Third genders in precapitalist societies

Although the bourgeois narrative of history would have us believe otherwise, ancient human history is rich with gender diversity. Historians have noted the existence of third genders on every continent, dating as far back as the late paleolithic era (50,000–10,000 BCE), if not even earlier (Greenberg 64). From society to society, gender systems varied widely, and third genders cannot be universalized outside of the cultural, economic, and ecological context in which they developed. For example, Navajo anthropologist Wesley Thomas identified four categories of sex and at least 49 different gender identifications within Navajo culture (Feinberg 49). An attempt to equate one of these Navajo sex categories or gender identifications with the third gender role of a society that only had three gender roles, for example, would be ahistorical. That said, by considering these diverse gender systems in contrast to the gender system of capitalism, which is defined by male supremacy, the oppression of women, and the suppression of third gender expression, we can identify some themes and draw certain conclusions about those gender roles and expressions that do not fit within the capitalist gender binary, for which I use the term “third genders” in the interest of being concise.4

Unlike in capitalist society, precapitalist societies often, but not always, had prescribed social roles for third gender people. That said, many precapitalist societies did not have a prescribed third gender role or actively suppressed third gender expression. For example, the Akimel O’odham, a southwestern Native American tribe, did not have a recognized third gender role, but did have a derogatory term for third gender expression (“wi-kovat”), and saw androgyny as a product of the witchcraft of the neighboring Tohono O’odham tribe, a tribe which did respect third gender expression (Williams 18). For another example, the ancient Hebrews also suppressed third gender expression, and Deuteronomy contains some of the earliest laws against crossdressing and even against sex reassignment surgery:

The woman shall not wear that which pertaineth unto a man, neither shall a man put on a woman’s garment: for all that do so are an abomination unto the Lord thy God (The Bible, Deut 22:5).

He that is wounded in the stones, or hath his privy member cut off, shall not enter into the congregation of the Lord (The Bible, Deut 23:1).5

In societies that did have established third gender roles, they tended to operate “above the fray,” so to speak, and often occupied an important position in the mediation of social relations. The most widespread social function of third gender people, to the point of it being a nearly ubiquitous role in societies that recognized third gender expression, was as religious leaders. There is extensive evidence from societies around the world that third gender expression played (and, where it hasn’t been stamped out, continues to play) a central role in religious practices. Relatedly, but distinctly, third gender people were (and are) often healers, mediators of disputes within their societies, and political leaders—frequently on the spiritual basis that their third gender expression was the special designation of a higher power, and/or that their ability to combine or move between masculine and feminine characteristics and roles gave them the enhanced ability to move between the physical and spiritual realms. Generalizing widespread practices among Native American tribes, historian Walter L. Williams writes:

The berdache [sic]6 receives respect partly as the result of being a mediator. Somewhere between the status of women and men, berdaches [sic] not only mediate between the sexes, but between the psychic and the physical—between the spirit and the flesh. Since they mix the characteristics of both men and women, they possess the vision of both. They have double vision, with the ability to see more clearly than a single gender perspective can provide. This is why they are often referred to as ‘seer,’ one whose eyes can see beyond the blinders that restrict the average person. Viewing things from outside the usual perspective, they are able to achieve a creative and objective viewpoint that is seldom available to ordinary people. By the Indian view, someone who is different offers advantages to society precisely because she or he is freed from the restrictions of the usual (Williams 41–42).

That analysis is based on Williams’ extensive research into one particular type of third gender expression that was (is) common in native North American societies, but it succinctly articulates a view of third gender expression that was commonplace around the world prior to the rise of capitalism. The conception of third gender people as mediators on both a physical and a spiritual level is echoed by many other precapitalist societies that had (or have) formal third gender roles. To name a few examples:

- The manang bali in Malaysia were curers, arbiters of disputes, and chiefs whose third gender expression was mandated by supernatural instructions (Greenberg 57)

- Mapuche machis in the southern cone of South America are custodians of tradition and healers whose power derives from communion with spirits (Bacigalupo 442)

- The mugawe of the Meru people of Kenya are religious leaders considered the complement to male political leaders (Greenberg 60)

- Ten percent of diviners among the Zulu in South Africa are third gender (Greenberg 60)

- The Korean mudangs were third gender sorceresses who had a special connection to the spiritual world due to their gender (Feinberg 45)

- Among the Lakota of North America, the ceremonial role of third gender people “exceeded those of the most distinguished ceremonial leaders” (Williams 32), a common theme across many indigenous North American cultures

- Third-gender expression was sacred to pagan peasants in what is today known as France (Feinberg 36)

- Records of transsexual priestesses who served female deities are widespread throughout the Middle East, North Africa, Europe, and western Asia (Feinberg 40)

The vast diversity of gender systems, which range from having two genders to having dozens, and the geographic distribution of that diversity around the world, with third genders appearing on every continent, and even neighboring societies having very different gender systems, is significant in and of itself. But more than that, it’s significant in the context of the international situation of today, where third gender people are persecuted almost universally around the world, except for the few places where precapitalist traditions persist despite severe repression from capitalist and imperial powers. When we compare the gender oppression of today to the gender diversity of the past, it begs the question: what the fuck happened?

Property, the first class division, and the nuclear family

In order to answer that question, we must trace the development of gender oppression back to its source in the emergence of class society. We will focus specifically on Europe because it was the petri dish from which the particular form we see today of capitalism and patriarchal gender relations emerged. In pre-capitalist Europe, as it did elsewhere, the development of agriculture created the conditions for the first form of private property: livestock. Generally, men were disproportionately responsible for acquiring food, and for the instruments needed to do so. As livestock increasingly became a source of wealth for families, the role of men in production increasingly became the center of gravity within the family. This shift gave men the material basis, class interest, motivation, and power to overthrow the matrilineal system of inheritance in order to be able to pass on their wealth to their own children, and instituting the oppression of women was a crucial aspect of the success of that overthrow. In order to prove male inheritance under the new patrilineal system, women’s sexuality had to be subject to oppression at the hands of men. Once mother right was overthrown by father right, men needed to be able to guarantee their paternity, which means they had to be able to guarantee their wife’s fidelity. Monogamy was imposed onto women and they were subjected absolutely to the will of their husbands. As Engels shows in his cornerstone work, The Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State:

The overthrow of mother right was the world historical defeat of the female sex. The man took command in the home also; the woman was degraded and reduced to servitude; she became the slave of his lust and a mere instrument for the production of children…. In order to guarantee the wife’s fidelity and therefore the paternity of the children, she is delivered over unconditionally into the power of the husband; if he kills her, he is only exercising his rights (Engels 46–47).

The initial division of labor between men and women within the home was thus transformed into the first class oppression. The nuclear family emerged as the unit of management for the man’s property: his slaves, his wife, and his children were all converted into instruments, a secondary form of property also belonging to him, for the management and cultivation of his primary source of wealth.

Within the new system, in order to reproduce male heirs as well as male workers, women had to be subjected to economic oppression as well. According to Engels, the nuclear family is both the “cellular form of civilized society” (Engels 54) and the vehicle for the oppression of women, “the subjugation of one sex by the other… a conflict between the sexes unknown throughout the whole previous prehistoric period” (Engels 53). As Sylvia Federici shows in Caliban and the Witch, when the proliferation of enclosures that accompanied the rise of capitalist private property began to result in the private appropriation of the productive labor of men, those men in turn began to appropriate the reproductive labor of women, leaving women in a situation of “double dependence” (Federici 97) or double oppression.

Federici shows that the enclosure of the commons7 “was amplified by the process of social enclosure” (84) whereby reproductive labor processes were transferred from the public sphere to the private. The effect that enclosures of the commons had on productive labor—namely that, at the expense of the newly forming proletariat, private interests began to control and benefit from socialized production processes that were previously carried out for public benefit—is mirrored in the way that reproductive labor, the labor of women, was brought under the control of men for them to exploit for their own benefit. This is the process by which the nuclear family became both a microcosm of broader economic processes and the basic unit of the reproduction of labor-power. Federici also shows that as proletarian men were dispossessed and exploited by processes of primitive accumulation, proletarian women were doubly dispossessed and exploited due to their reproductive role within the family:

According to this new social-sexual contract, proletarian women became for male workers the substitute for the land lost to the enclosures, their most basic means of reproduction, and a communal good anyone could appropriate and use at will…. This was for women a historic defeat… a new patriarchal order was constructed, reducing women to a double dependence: on employers and on men (Federici 97).

That economic reordering of gender roles was accompanied by a tectonic shift in ideas about gender, whereby “it was established that women were inherently inferior to men… and had to be placed under male control” (Federici 101).

The violence required to establish traditional & oppositional sexism

The oppression of women could not have been imposed without a massive, bloody campaign of repression that spanned centuries; it is only logical that such a profound degradation of the social and economic status of half the population of Europe required the use of equally profound repressive measures to enforce it. This was carried out by an alliance between the Catholic Church, emerging European states, economic measures from the ruling class, and individual men who committed interpersonal violence against women. Federici traces the “war against women, carried out over a period of at least two centuries” (164) that used mass sexual violence, torture, and murder in order to forcibly subjugate women. It specifically targeted women accused of witchcraft, on the basis of their practicing folk medicine, having miscarriages or abortions, arousing sexual desire in men, being unmarried, being poor or propertyless, etc.—offenses which notably all ran counter to the new capitalist social relations and gender norms. The witch hunt was a tool of social control that empowered the capitalist class, emerging European states, and especially the Catholic Church to compel women and men alike to fall in line with the new economic arrangement under threat of death. Of the division the witch hunt created between proletarian men and women, Federici writes:

Undoubtedly, men’s failure to act against the atrocities to which women were subjected was often motivated by the fear of being implicated in the charges, as the majority of the men tried for [witchcraft] were relatives of suspected or convicted witches. But there is no doubt that years of propaganda and terror sowed among men the seeds of a deep psychological alienation from women, that broke class solidarity and undermined their own collective power (189).

By creating a fundamental division between proletarian men and women, economically and ideologically, the ruling classes effectively undercut any resistance to their rule.

Women had previously operated as authorities on matters of childbirth, which involved a much greater degree of control over not only their own sexualities and sexual practices, but also over medicinal practices and spiritual traditions. However, with the rise of capitalism and the establishment of patriarchy,

women were expropriated from a patrimony of empirical knowledge, regarding herbs and healing remedies, that they had accumulated and transmitted from generation to generation, its loss paving the way for a new form of enclosure. This was the rise of professional medicine, which erected in front of the “lower classes” a wall of unchallengeable scientific knowledge, unaffordable and alien, despite its curative pretenses (Federici 201).

Federici shows the sweeping effect of the witch hunt on every aspect of women’s lives in Europe such that, by the time the witch hunt wound down at the end of the 17th century, proletarian women had been completely brought under the control not just of capitalist labor processes, but of a capitalist worldview, both of which rested on the subjugation of women as a primary condition.

As proletarian women during this time period were undergoing a double dispossession (the enclosure of the commons and the new sexual division of labor), significant sections of the European masses were undergoing an even more absolute dispossession due to the new gendered order, which required an equally bloody campaign of repression against third gender people and anyone who defended them.In order to stamp out third gender expression in Europe, the ruling class had to resort to extremes of violence. For example, in the late 300s CE, only ten years after adopting Christianity as its official religion, the Roman government began to pass laws against third gender expression, accompanied by patriarchal polemics from the ruling class, as Feinberg shows:

“We cannot tolerate the city of Rome, mother of all virtues, being stained any longer by the contamination of male effeminacy…” But shortly after the law passed, at least one dramatic act of resistance to this murderous anti-trans legislation was recorded. The head of the militia in Thessalonica in northern Greece, a Goth named Butheric, arrested a famous circus performer who was well-known for his femininity. But the performer was loved by the masses. When news spread of his arrest, the people rose up in rebellion and killed Butheric. The outraged Gothic authorities reportedly rounded up the nearby population and butchered three thousand people as collective punishment. (Feinberg 64)

This was the level of violence and terrorism that was required to break the tradition of third gender expression around the world, and it was indispensable to the rise of capitalism.

Of the bloody campaign of repression against women that raged throughout Europe during the early transition to capitalism, Federici writes:

The witch hunt deepened the divisions between women and men, teaching men to fear the power of women, and destroyed a universe of practices, beliefs, and social subjects whose existence was incompatible with the capitalist work discipline, thus redefining the main elements of social reproduction (165).

Her argument about “the ‘original sin’ in the process of social degradation that women suffered with the advent of capitalism” (164) and the subsequent destruction of “a universe of practices, beliefs, and social subjects” (165) would have been strengthened had she taken into account the repression of third gender people carried out during the transition to capitalism. The following argument, already strong in its own right, would also have been strengthened by consideration for the suppression of third genders:

[M]ale workers have often been complicitous with this process, as they have tried to maintain their power with respect to capital by devaluing and disciplining women…. But the power that men have imposed on women… has been paid at the price of self-alienation, and the ‘primitive disaccumulation’ of their own individual and collective powers (Federici 115).

This is undoubtably true, and it is equally true that with any concessions that women have made to the binary gender relations of capitalism, in the past or in the present, they have capitulated to their own gendered oppression, although those concessions may have appeared on the surface to be in their immediate interest. Not only were proletarian women forcibly removed from the social position they had previously occupied and placed in a subservient one in order to serve the interests of the ruling class, the destruction of the “universe” of social relations and spiritual practices that was necessary for their subjugation would not have been possible without the repression of third genders and the establishment of the gender binary.

This is because what biologist and gender theorist Julia Serrano calls traditional sexism—male supremacy and the oppression of women—requires, in order to operate, a rigidity of gender roles that Serrano calls oppositional sexism. In other words, in order for men to be superior and women inferior, it must first be accepted that “female and male are rigid, mutually exclusive categories, each possessing a unique and nonoverlapping set of attributes, aptitudes, abilities, and desires” (Serrano 13). The existence of third gender people, who were widely respected and even revered around the world for their ability to move between and even transcend the categories of male and female, could not be admitted within the new system, which took oppositional sexism as its starting point. As Serrano writes, “[t]he fact that a single individual can be both female and male… at different points in their life challenges the commonly held belief that these classes are mutually exclusive and naturally distinct from one another” (Serrano 59). To get more specific, on the one hand, no women under the new patriarchal system could be permitted any options for escaping the oppression they faced on the basis of gender. On the other hand, if any men under the new patriarchal system were to renounce their inherited supremacy, that would threaten the very foundation of the system. In modern parlance, Serrano explains this concept further:

In a male-centered gender hierarchy, where it is assumed that men are better than women and that masculinity is superior to femininity, there is no greater perceived threat than the existence of trans women, who despite being born male and inheriting male privilege ‘choose’ to be female instead. By embracing our own femaleness and femininity, we, in a sense, cast a shadow of doubt over the supposed supremacy of maleness and masculinity. In order to lessen the threat we pose to the male-centered gender hierarchy, our culture… uses every tactic in its arsenal (Serrano 15).

In other words, third gender expression constitutes an existential threat to patriarchy because its very existence runs counter to the ideological foundation of patriarchy.

Going beyond the ideological, third gender people also pose an existential threat to patriarchy due to the role that third gender people generally played in precapitalist societies of mediating social relations, whether as religious leaders, healers, political leaders, arbiters of disputes, custodians of traditions, or any of the many other kinds of work ascribed to third gender people that served this broader social function. The emergence of class divisions in Europe that began with the imposition of patriarchy was not simply an economic change, but a social, political, and ideological one that was inextricable from the simultaneous overthrow of the social relations, spiritual practices, political structures, and cosmovision that corresponded to the previous economic system. Given that third gender people played a leading role in the mediation, conservation, and proliferation of these aspects of precapitalist society, it follows that they had to be dispensed with as a class in order for the practices and ways of life that they stewarded to be thoroughly destroyed. A major aspect of that social, spiritual, and ideological destruction was the rise of the Catholic Church as the new mediator of the social relations of the new economic system. In order to cement its hegemony, the Catholic Church carried out draconian persecution and repression directly, sometimes in collaboration with the European feudal powers and emerging nation states. Beyond that, it inculcated a new ideology in the European peasantry and proletariat that produced and reproduced the new capitalist social relations, with the Church placed squarely at the center, and undermined the old ones.

The laws in Deuteronomy provided much of the ideological basis for the Catholic Church’s later persecution of third gender people, and the process in precapitalist Europe of the simultaneous emergence of private property, male supremacy, the oppression of women, and the suppression of third gender practices can be seen from start to finish with a closer look at ancient Hebrew society. The ancient Hebrews began the process of accumulating wealth through settled agriculture and raising livestock earlier than their neighbors. The accumulation of wealth in the form of herds was the material basis for a shift in the formerly matrilineal society toward patrilineal inheritance, which required subjugating women both within the household and in society at large to the dominance of men. Flowing from this first class oppression, class divisions among the Hebrews deepened, and wealth began to be increasingly concentrated in the hands of the minority.

Internally, in order to maintain their control, the ruling class increasingly needed to work to maintain their domination against the other classes of people within their society. In part, this meant invoking oppositional sexism as the basis for male supremacy and the oppression of women.

[W]ealthy Hebrew males were trying to consolidate their patriarchal rule. That means they were very much concerned about making distinctions between women and men, and eliminating any blurring or bridging of those categories. That would also explain why the rules of ownership of property and the rights of intersexual people were extensively detailed in Jewish law (Feinberg 51).

Third gender expression undermined the basis for oppositional sexism, and by extension traditional sexism, upon which Hebrew class divisions rested.

Externally, Hebrew society had to distinguish itself from its neighbors socially and politically in order to protect its emerging class structure and religious practices against the pressure of the status quo from its neighbors. This required a new set of religious beliefs and practices that increaingly conflicted with those of the other societies in the region:

The communal religious beliefs of the Hebrews had not been fundamentally different from that of other polytheistic tribal-based religions of that region. They worshipped numerous deities, including Yahweh…. what is clear is that Deuteronomy reflects the deepening of patriarchal class divisions among the Hebrews, who lived in and around communal societies that still worshipped goddesses…. [R]itual sex change was a sacred path for many priestesses of these matrilineal religious traditions. [Deuteronomy’s] rules could be seen from the point of view that cross-dressing and cross-gendered expression as a whole retained an integral connection to the worship of the Mother Goddess (Feinberg 50).

Third gender expression was a cornerstone of religious practices that were incompatible with the new economic structure, and the Hebrews therefore needed to suppress it in order to ensure the survival of their economic system. This dovetailed with the internal function of oppositional sexism, in that the Hebrews were able to use oppositional sexism in order to define themselves against neighboring societies. For these reasons, the ancient Hebrews declared in no uncertain terms that third gender expression would not be permitted.

Colonialism and patriarchy

The repressive measures and patriarchal ideologies that were tested on the European peasantry and proletariat during the witch hunt and the transition to capitalism were soon exported to the rest of the world with the advent of colonialism. A closer look at Spain’s colonization of Latin America demonstrates the continuity between the imposition of patriarchy to serve the growth of capitalism within Europe and its deployment in the Americas in order to expand early capitalist economies and bring the Americas under colonial control.

Although “by the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Europe was in the midst of an extremely homophobic outburst” (Williams 131), not every region in Europe had taken up the suppression of homosexuality and third gender expression to the same degree. Spain in particular was in the midst of a battle for national sovereignty, in which the European natives were fighting to reclaim their territory from the Islamic Empire, which had occupied Spain since the 700s CE, by way of the ethnic cleansing of Muslims and Jews: the Inquisition. Homophobia was a key tool of the Spanish fight for sovereignty because acceptance of homosexuality was a dividing line that separated the Spanish Catholics from the Moors (Muslims in what is today Spain):

In technology and intellectual thought, the Islamic civilization of the Moors was clearly more advanced than that of the Castilians. If the Spanish were going to challenge their culturally superior Muslim enemy, they were going to have to overcome their sense of inferiority by overcompensating—they had to see themselves as superior. They obviously could not do this in regard to technological or intellectual matters, so they had to turn to ideological values. In short, the Spanish had to create a culture that emphasized its difference from the Moors. Christianity, with its intolerance for other religions, served that function, supplying a unifying theme around which the non-Muslim Spanish could rally and proclaim their superiority…. One aspect of Moorish society that clearly stood out as different from the Christians was its relaxed attitude toward same-sex relations…. They might not be able to challenge the Moors on technological or intellectual grounds, but they could do so by emphasizing “morals”—social taboos that the Muslims did not share (Williams 133–134).

By leveraging homophobia against the Moors, the Catholics were able to unite behind a shared identity and set of values that provided the ideological motor behind their struggle to take back control from the Moors. What’s more, accusations of homosexuality were used as justification for the Catholic Church to seize the property of the accused individuals, so fanning the flames of homophobia was a winning strategy for the Church to quickly “gain a vast base of wealth in Spain as well as eliminate possible competitors for control of the population” (Williams 134) by expropriating the property of the Moors. Because of these driving factors, in addition to the cultural emphasis on population growth among Catholics that accompanied the expulsion of the Moors, “the Inquisition reached sadistic extremes in its suppression of sexual diversity…. Sodomy was a serious crime in Spain, being considered second only to crimes against the person of the king and to heresy. It was treated as a much more serious offense than murder” (Williams 132).

Just as the Inquisition was winding down, the Spanish began to colonize the Americas in earnest, and with homophobia at the height of its influence over Spanish culture, the stage was perfectly set for the tragedy that would come:

To their horror, the Spanish soon discovered that the Native Americans accepted homosexual behavior even more readily than the Moors. Since this was an inflammatory subject on which the Spanish had strong feelings, the battle lines were soon drawn. Sodomy became a major justification for Spanish conquest of the peoples called Indians…. With their belief that same-sex behavior was one of God’s major crimes, the Spanish could easily persuade themselves that their plunder, murder, and rape of the Americas was righteous. They could fight their way to heaven by stamping out the sodomites, rather than by crusading to the Holy Land. The condemnation of Indian homosexual behavior was a major factor in proving the virtue of the Spanish conquest, and the conquistadors acted resolutely to suppress it by any means necessary (Williams 134–137).

The onslaught of violence against homosexuality and third gender expression that Spanish colonizers unleashed against Native Americans was one aspect of the larger process of colonization in which Spain rearranged the economic systems, social relations, and cosmologies of the societies they colonized. The interdependence of these different aspects of indigenous societies and the devastating impact of colonization on every level is a recurring theme that is revealed again and again through specific historical moments. For example, an anti-colonial, pan-Andean movement centered on the worship of the huacas (local gods) gained traction among indigenous people in modern-day Peru in the 1560s:

The huacas were mountain springs, stones, and animals embodying the spirits of the ancestor. As such, they were collectively cared for, fed, and worshipped for everyone recognized them as the main link with the land, and with the agricultural practices central to economic reproduction. Women talked to them, as they apparently still do, in some regions of South America, to ensure a healthy crop. Destroying them or forbidding their worship was to attack the community, its historical roots, people’s relation to the land, and their intensely spiritual relation to nature. This was understood by the Spaniards who, in the 1550s, embarked in a systematic destruction of anything ressembling an object of worship (Federici 226).

Not only did the Spanish colonizers destroy the huacas physically, they attacked the social fabric of the region by forcibly rearranging people geographically, breaking social ties in addition to ties between people, their land, and their religious practices. Repression in the form of the witch hunt proved indispensable to this process:

Further, a resettlement program (reducciones) was introduced removing much of the rural population into designated villages, so as to place it under a more direct control. The destruction of the huacas and the persecution of the ancestor religion associated with them was instrumental to both, since the reducciones gained strength from the demonization of the local worshipping sites. It was soon clear, however, that, under the cover of Christianization, people continued to worship their gods, in the same way as they continued to return to their milpas (fields) after being removed from their homes. Thus, instead of diminishing, the attack on the local gods intensified with time, climaxing between 1619 and 1660 when the destruction of the idols was accompanied by true witch-hunts, this time targeting women in particular… [and] conducted according to the same pattern of the witch-hunts in Europe (Federici 227).

In her analysis of the anti-idolatry campaigns carried out by the Spanish colonizers, Federici gestures to the role homophobia played as both a weapon of and a motivating factor behind colonialism, but she understates its importance, not just in the colonization of the Americas, but also in the development of capitalism in Europe. Furthermore, homophobia is only one form of patriarchal repression against gender roles and expressions that do not conform to the capitalist system of gender. Federici was remiss to mention homophobia as simply a taboo or stigma against sodomy, without contextualizing it as one aspect of the violent campaign of repression against third genders that began in Europe as the basis of primitive accumulation during the early capitalist period and was then exported to be carried out in the rest of the world via colonialism and genocide.

The many cultures across the Americas that had established third gender roles and respect for third gender expression fought back against the imposition of homophobia and oppositional sexism by the colonizers. For one example, among the Mapuche people in modern-day Chile,

shaman religious leaders were all berdaches [before colonization]. When the Spanish suppressed this religious institution because of its association with male-male sex, the Indians switched to a totally new pattern. Women became the shamans…. Such examples may lead us to speculate that once Indians realized how much the Europeans hated sodomy, indigenous groups in various areas of the Americas quickly adapted to colonial control by keeping such things secret (Williams 141).

For another example:

One agent in the late 1890s… tried to interfere with Osh-Tisch, who was the most respected badé.8 The agent incarcerated the badés, cut off their hair, made them wear men’s clothing. He forced them to do manual labor…. The people were so upset with this that Chief Pretty Eagle came into Crow Agency, and told [the agent] to leave the reservation. It was a tragedy, trying to change them (Williams 179).

As the suppression of third gender people and large-scale acts of violence against them and those who defended them had served the purpose within Europe of degrading the pre-capitalist social fabric to the point that social relations could be entirely reworked in favor of capitalism, it served the same purpose in the Americas. By expelling third gender people from their respected social positions, by forcing them into hiding, and in some places, by eradicating third gender practices altogether, European colonizers rearranged the social relations of Native American societies and established new systems of gender, political structures, and religious practices that promoted and perpetuated the colonial dispossession of indigenous people and the capitalist exploitation of the people and natural resources of the Americas. As capitalism continued to develop around the world, the suppression of third genders remained a pillar of capitalist social relations.

Prewar, postwar, 1960s, and the reemergence of third genders

The reemergence of third gender expression in Western society has been a process of reshuffling of gender roles that can be traced back to economic changes that took place during the first and second world wars. During World War I, young men who were enlisted into the army were geographically mobile and tended to be concentrated in coastal cities, and spent the vast majority of their time in male-only environments. These conditions led to thriving gay male social scenes and networks in most major cities in the United States and Europe. At the same time, women in the US were being recruited into factory work while the men were off in the army. This led to increased economic independence for women, which in turn contributed to the flourishing of butch/femme culture and lesbian social scenes around the country. From the beginning of the 20th century through the end of the 1930s, the nuclear family’s grip loosened slightly, and there was significant freedom for people to choose homosexual lifestyles, including casual sex with multiple partners, as well as monogamous relationships that were notably different from heterosexual relationships because they did not serve the economic functions of reproducing workers for capitalism (one male breadwinner who is engaged in productive labor, while his wife is responsible for reproductive labor as well as literally reproducing with him).

Modern readers who understand sexuality and gender as inherently separate, distinct categories might question the connection of this history of homosexual activity to the history of third genders. However, during this time period, sexuality was primarily determined by whether a person’s gender expression was feminine or masculine. Feminine men were “fairies,” considered the real homosexuals, while masculine men were “trade” and were more likely to have sexual and romantic relationships with both men and women. Similarly, masculine women were “butches” who usually exclusively dated women, and feminine women were “femmes” who were more likely to have relationships with both men and women. Feminine gay men and masculine lesbians faced discrimination primarily for their gender expression, and their sexual orientation was seen as the product of their gender.

During the post-World War II period, economic prosperity and loss of life to the wars put economic pressure on American and European societies to increase birth rates, which, in addition to a revanchist backlash against the sexual freedom of the prewar period, caused a cultural shift back toward traditional gender roles and the nuclear family. Furthermore, the advent of the Cold War required a cultural swing toward conservatism among the American populace, media, and government in order to unite Americans in a cultural identity that stood in opposition to the Soviet Union. The postwar period saw severe repression against third gender expression that included vigilante violence, hateful sentiment stirred up by religious fundamentalists, employment and housing discrimination, and police repression.

By the late 1960s, the proliferation of progressive social movements had, in opposition to postwar revanchism, affected an ideological shift among wide sections of the US populace. A genuine revolutionary movement was beginning to take shape, spearheaded by revolutionary anti-war activists and revolutionary nationalist groups such as the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, and the American Indian Movement. Large sections of the country swung into political motion, including the urban proletariat, high school and college students, and soldiers and veterans, and their demands included but went far beyond their immediate interests—the horizon was set to revolution. Although the revolutionary movement of the 60s was crushed within a (long) decade, and it was never able to accomplish its full aims, it did create cracks in the dam that was holding back revolutionary activity in the US.

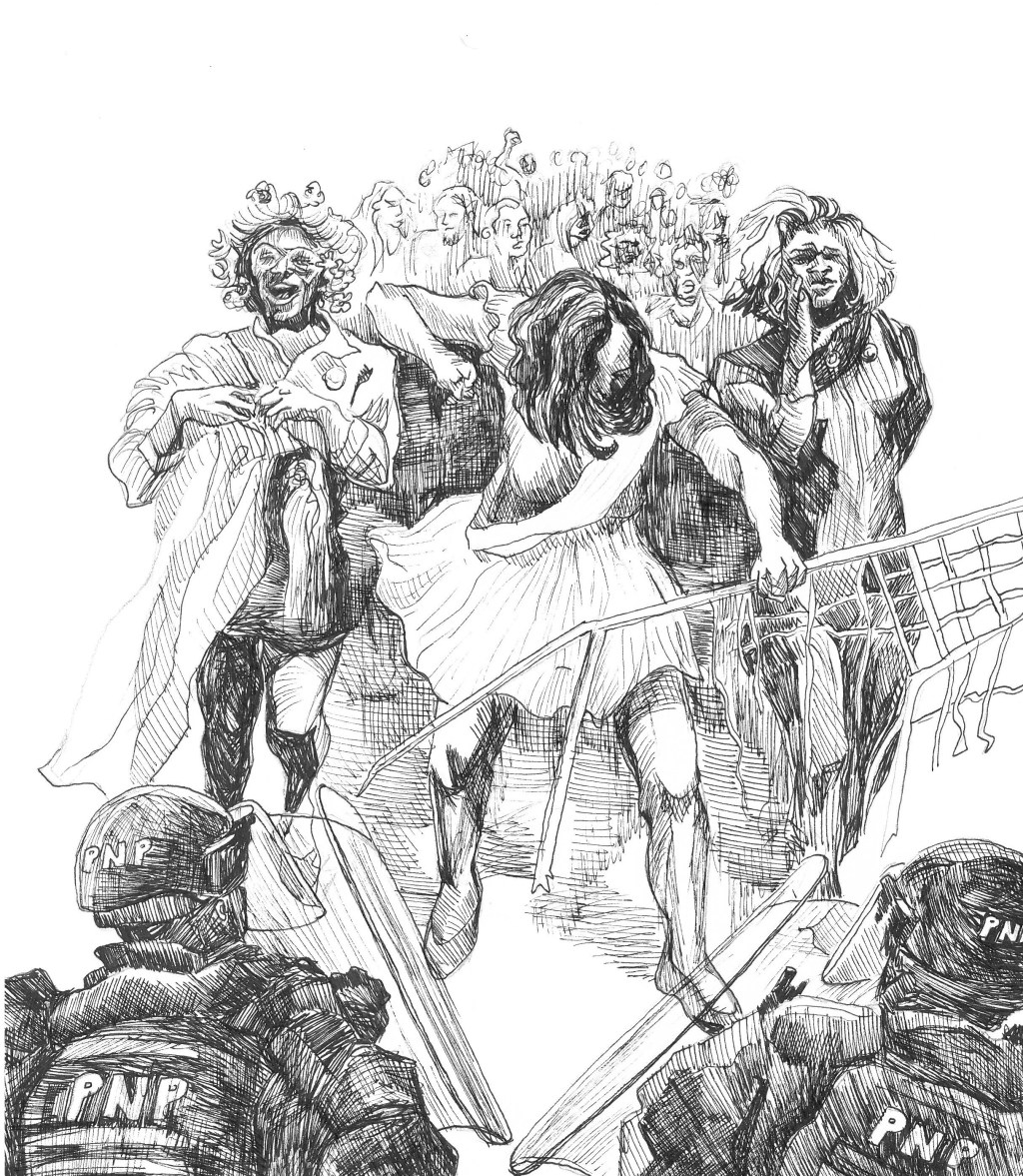

Due to the broad influence of the revolutionary movement on oppressed people in the US, as well as the formal involvement of gay and transgender people in revolutionary organizations, there were many spontaneous uprisings throughout the late 60s and early 70s of gay bar patrons, crossdressers, trans sex workers, and homeless gay youth that led to class struggle against anti-gay institutions and militant confrontations with the police, the 1969 Stonewall Rebellion being the most widely known example of this. In the wake of Stonewall, a number of gay organizations, such as the Gay Liberation Front and Gay Activists Alliance, were formed. These organizations ranged politically, with some claiming to be revolutionary, while others not so much, but regardless of these differences they continued to wage mass struggle around issues affecting gay people. In the wake of the 1970 Weinstein Hall Occupation,9 transvestite activist Sylvia Rivera formed the organization Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR). In a statement, she polemicized against some of the problems she saw within the gay rights movement at the time:

GAY POWER – WHEN DO WE WANT IT? OR DO WE?

This is the question that is running through our minds. Do you really want Gay Power or are you looking for a few laughs or maybe a little excitement. We are not quite sure what you people really want. If you want Gay Liberation then you are going to have to fight for it. We don’t mean tomorrow or the next day, we are talking about today. We can never possibly win by saying “Wait for a better day” or “We’re not ready yet”. If you’re ready to tell people that you want to be free, then your10 ready to fight. And if your not, then shut up and crawl back into your closets. But let us ask you this, Can you really live in a closet ? We can’t.

So now the question is, do we want Gay Power or Pig Power? We are willing to admit that we need the Pigs. But we only need them for crime control. We do not need them to beat and harass our Gay brothers and sisters. The Pigs are not helping the people who are being robbed on the streets and being murdered. How can they when they’re to busy trying to bust a Homosexual over the head. Or they’re to busy trying to catch someone hustling so that they can arrest them. But they do give us an alternative. All we have to do is commit sodomy with them and they’ll forget they ever saw us. Untill next time that is. So again we ask you, do you want Pig Power or Gay Power? This is up to each and every one of you.

If you want Gay Power then you’re going to have to fight for it. And you’re going to have to fight untill you win. Because once you start you’re not going to be able to stop, cause if you do you’ll lose everything. You won’t just lose this fight, but all the other fights all over the country. All our brothers and sisters all over the world will return to their closets in shame. So if you want to fight for your rights, then fight till the end.

We would also like to say that all we fought for at Weinstein Hall was lost when we left upon request of the Pigs. Chalk one up for the Pigs, for they truly are carrying their Victory Flag. And realize that the next demonstration is going to be harder, because they now know that we scare easily.

You people run if you want to, but we’re tired of running. We intend to fight for our rights until we get them.

The influence of queer house culture propelled STAR beyond fighting within the confines of bourgeois morality and social acceptance, a weakness which plagued much of the gay liberation movement at the time. Before, during, and after the organization’s formal existence, STAR leadership (Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson) were mothers to dozens of homeless queer youth, running shelters out of whatever spaces they could find, whether that be abandoned semi-trucks or mafia-owned, condemned buildings. Two sweet details show the qualitative impact of house culture on STAR, culturally and politically:

- In STAR House and the other shelters, Santa Barbara, the patron saint of homosexuality, was worshipped collectively by Rivera and other residents who practiced Santería.

- When, after the death of her husband and pet dog, Johnson suffered a mental breakdown that led to her hospitalization at Wards Island State Hospital, STAR organized a march to the hospital and held a candelight vigil there in her honor, that was also a protest against the treatment of gay and transgender people in hospitals and prisons.

These anecdotes demonstrate an ideological disposition toward seeing the deep underlying connections between economic oppression, discrimination, religion, and the nuclear family, as well as between personal relationships and objective conditions, that I see as flowing from the organization of gay and trans youth into houses.

The political significance of house culture has sadly been misappropriated and warped by today’s counterrevolutionary, post-mutual aid, “existence is resistance”-style queer pseudo-activism. The fact is, before the concept was defanged by postmodernism, gay and trans houses were (and are, where the practice still exists) the frontlines of the fight for the lives of trans youth, protecting youth from suicide, overdoses, sexual violence, and homelessness. They operated as a social fabric that not only attempted to compensate for the absence of traditional nuclear families in the lives of trans people, but actually posed a threat to the nuclear family by offering an alternative family structure that protected and nurtured the very people and practices that the nuclear family was designed to eradicate. House culture, its impact on revolutionary trans organizing during the 1960s and 70s, and its legacy in the form of the chosen family, which continues to be practiced by many trans people today, offers a powerful lesson to today’s revolutionaries. If we aim to tear up the roots of patriarchy through the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism, we’ll need to weave together a new set of social relations, new spiritual practices, and new forms of giving and receiving love that correspond to, and strengthen, the new economic organization of society from each according to ability, to each based on need. House culture not only offers us a glimpse into the possibilities for post-capitalist kinship systems, but it actually provides us with a model.

STAR’s first public appearance as an organization was at a Young Lords Party (YLP) march for Puerto Rican liberation, which STAR joined in order to protest police brutality. STAR maintained a relationship with the YLP during its years of activity, and YLP members acted as Rivera’s bodyguards when she received death threats for fighting for justice for an inmate murdered by COs on Rikers Island. STAR was heavily involved in fighting against the abuse and neglect of gay and trans people in prisons and mental hospitals, and fought for democratic rights for gay and trans people in many areas of society; for example, by protesting discrimination against homosexual college students.

However, their program11 didn’t start and end with democratic rights, but understood waging class struggle around democratic rights as a part of a broader fight that stretched to ending the exploitation of and discrimination against transgender people and establishing a revolutionary people’s government. Inspired by socialist China and the Black Panther Party’s 10 Point Program, their program reflects the understanding that in the fight to end the oppression of trans people, and, additionally, in the context of waging revolution, fighting for democratic rights is necessary, but not sufficient. Fighting for rights such as access to healthcare can be an important part of waging struggle against the capitalist system that is oppressing trans people, so long as the fight doesn’t end once some rights are won. From the moment the class struggle subsides, the ruling class will begin dismantling those rights because democratic rights are not sufficient for ending the oppression of trans people. In and of themselves they can’t end the oppression of trans people because they fall short of a revolution, and therefore fall short of doing away with class society. A communist vanguard is needed in order to carry the struggles for democratic rights beyond the narrow confines of bourgeois democracy and toward revolutionary ends.

STAR began to decline within a couple years, and a confrontation between Sylvia Rivera and trans-exclusionary gay rights activists at the 1973 Christopher Street Day Parade was the final nail in STAR’s coffin. By this date, many of the gay rights organizations formed in the wake of Stonewall had taken a conservative turn toward fighting for acceptance from and inclusion in mainstream society, at the expense of sacrificing the more radical or less respectable elements among them—namely, trans people. Likely due to influence from the rest of the gay liberation movement, even STAR’s orientation had shifted by this point toward achieving recognition for trans people within both the gay liberation movement and society overall, rather than mobilizing gay and trans people in class struggle against the institutions oppressing them.

This kind of political degeneration can be expected, given that no one is immune to the effects of bourgeois ideology, which is constantly being adapted to respond to changing conditions and deployed to neutralize threats to bourgeois rule, through exerting ideological influences that can lead even the most well-meaning and militant individuals and organizations down dead ends. As revolutionaries, our only defense against the backwards pull of bourgeois ideology is a communist vanguard party dedicated to overthrowing the bourgeoisie and establishing the dictatorship of the proletariat. Without the leadership of such a vanguard party, any organization will inevitably be either destroyed by the forces of bourgeois rule or domesticated and confined to the “acceptable channels” of capitalist society. To accentuate this point, it’s worth mentioning that by 1973, the Black Panthers and Young Lords were also flying off the rails, due to brutal state repression as well as their own internal weaknesses, dogmatism and incorrect lines, that left them unable to overcome that repression.12 STAR had no future in the absence of the revolutionary movement that had created the conditions for the formation of the organization, and of the gay liberation movement more broadly, in the first place.

More on the need for revolution

The oppression of women within the family is enshrined by legal systems that formally require that marriage “be a contract freely entered into by both parties” (Engels 59), giving equal rights to men and women on paper, while allowing the root cause of the inequality between men and women, the economic oppression of women, to persist unchallenged. In keeping with his point that the nuclear family represents the basic economic unit of class society, and is therefore a microcosm of the social relations and contradictions that exist in the society more broadly, Engels wrote:

This purely legalistic argument is exactly the same as that which the radical republican bourgeois uses to put the proletarian in his place. The labour contract is supposed to be freely entered into by both parties. But it is considered to have been freely entered into as soon as the law makes both parties equal on paper. The power conferred on the one party by the difference of class position, the pressure thereby brought to bear on the other party—the real economic position of both—that is not the law’s business…. As regards the legal equality of man and woman in marriage, the position is no better. Their legal inequality, bequeathed to us from earlier social conditions, is not the cause but the effect of the economic oppression of the woman (Engels 59–60).

His analysis shows that the oppression of women is not simply a result of legal or interpersonal discrimination, but that it flows from the economic oppression of women as a class, and it can therefore only be ended through the overthrow of class society. Any measures to fight the oppression of women short of proletarian revolution are half-measures that are inadequate to address the root of the problem. This crucial insight has subsequently been proven right by the advances women have been able to make in communist revolutions around the world, including in Russia, China, and the Philippines. In the words of Filipina revolutionary Coni Ledesma:

China under Mao saw the start of the full liberation of women. One of the first things Mao did was to take away the practice of the binding of the feet of Chinese women. Then women became part of production. The care of children was collectivized. There were many other policies that liberated women from the isolation of the home.

Revolutionary women [in the Philippines] have put into practice some of these practices. In the guerrilla zones, women are organized in Makibaka [a revolutionary women’s organization]. They are elected in leadership positions in the organs of political power. There is collective care of the children. Filipino women have learned from the example of China under Mao….

Women joined the revolutionary movement from the very start…. Frankly, I do not know if there were specific policies made to ensure the active participation of women. I think it was normal that women also joined the movement….

The challenge is always to politicize women in their numbers. As we say, to arouse, organize, and mobilize the largest number of women to participate in the revolution. It is only in participating in the revolution that women can work for their liberation (Ledesma 49–50).

Women revolutionaries like Lesedma around the world have proven that the most significant advances in dismantling the oppression of women are made when women take a leading role in the fight for revolution, and against capitalism-imperialism. The women revolutionaries of the Philippines are living proof to trans people today that the quickest, most effective, and most comprehensive way to end our own oppression is the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism-imperialism.

The situation of third genders today

The 1970s, 80s, and 90s saw US politics and culture swing hard to the right, with the advent of neoconservatism giving rise to countless social wars—on drugs, on poverty, on crime, on homosexuality, you name it—that finally reached a head in the 80s and early 90s with the crack “epidemic” and the AIDS “epidemic.”13 Despite the devastation that the 80s wrought on gay and trans individuals, social ties, and culture, the 60s had marked a turning point in the reemergence of third gender people as a force in society. The gay liberation movement, particularly ACT UP’s militant activism against the AIDS genocide, succeeded in winning a number of democratic rights for gay people which sometimes incidentally also benefitted trans people and which opened the door to the continued struggles for the democratic rights of gay and trans people in future decades.

Today, the nuclear family is in an advanced stage of decomposition. Infinite social and economic factors have contributed to the nuclear family’s gradual decline, from the impact of the mass incarceration of Black men on Black family structures, to rising divorce rates due to the increased economic independence of women, to an all-around lessened emphasis on marriage among younger people due to the decline of the influence of Christianity, to a drop in birth rates that can be at least partially explained by the economic hardships involved in raising a child and greater access to contraceptives. Most important for our purposes are the economic changes that have allowed for the loosening of gender roles: labor processes are more flexible now, with a bloated petty-bourgeoisie, on the one hand, and a growing gig economy, on the other hand. And although the gendered wage gap persists, many of the more strictly gendered jobs of the past, such as industrial manufacturing work, on the one hand, or secretarial work, on the other, have either declined in popularity, become obsolete entirely, or gradually become more integrated in terms of gender.

The informalization and gradual de-gendering of work overall has created the basis for gender roles to become more flexible, as reproductive work is increasingly being outsourced by individuals to exploited service workers, rather than being carried out within the nuclear family, as demonstrated by the rise in popularity of delivery services like UberEats and DoorDash, and subscription services like HelloFresh (meal kit subscription) and Nuuly (clothes box subscription) among the petty-bourgeoisie. These economic changes have occurred in tandem with wins around the bourgeois-democratic rights of gay people, such as the Supreme Court decision to legalize gay marriage in 2015, the inclusion of gay people in many mainstream institutions, such as the repeal of the military’s Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy in 2010, and the landmark Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009, which expanded federal hate crime laws to include sexual orientation and gender identity as a qualifying basis for identifying a hate crime. The incorporation of homosexual relationships into mainstream society, despite the fact that it occurred on patriarchy’s terms, and was based on claims that gay people can conform to the institutions of capitalism just as well as straight people can, is also a contributing factor to the overall loosening of gender roles that we see today. These conditions have created the basis for the reemergence of third gender expression as a major force in our society, while they have at the same time created a sharper divide between those who can sufficiently imitate heterosexuality and those who can’t.

After centuries of near-total repression, third gender expression has reemerged on the scene in a major way, but rather than being “above the fray” of social relations as they were in precapitalist societies, third gender people are now in the middle of the fray: at the center of some of the most heated social conflicts of our time, over key issues such as healthcare, education, sexual violence, the family, and the contested right to public spaces such as bathrooms. The increased public awareness of the existence of transgender people as a group that resulted from the “visibility, inclusion, and acceptance” program of the mainstream gay rights movement of the past several decades, as well as the decreasing economic basis for binary gender roles, has provoked a revanchist backlash that wields trans people as a scapegoat, creating chaos that obscures class relations and unites large sections of the proletariat and petty-bourgeoisie behind the ruling class’s agenda. The recent Supreme Court ruling that upheld Tennessee’s state ban on gender affirming care for trans youth, one of countless revanchist attacks on the democratic rights of trans people in the past decade, is an example of this. When diabetics are dying because they can’t afford insulin, when lives are being cut short by addiction due to doctors coercing their patients into taking opioids, when Black mothers die in childbirth at astronomical rates because of medical discrimination, when medical debt is the number one reason Americans declare bankruptcy, the majority of the country certainly would stand to benefit from rising up against the healthcare system, and at least demanding concessions from the bourgeoisie, if not waging a full-blown revolution. In that context, denying life-saving medical care to trans people categorically is not only a slow genocide against trans people, it is also a move to obscure the real enemy and unite the majority of the country around taking away another group’s access to healthcare in order to prevent that majority from fighting to improve their own healthcare.

To be clear, while the scapegoating of trans people in order to divide and mislead the proletariat is certainly a convenient result of the revanchist attacks on trans people, it isn’t the cause of those attacks. The reason trans people are under attack today is the same reason third gender expression has been subject to attempted annihilation for the past 500 years: the normal functioning of class society requires clearly demarcated class divisions, such that one class is subject to repression at the hands of another. In the case of the oppression of women, essential to the functioning of capitalism in addition to being identified by Engels as the first ever class division, third genders, which predate the existence of class society by millenia, threaten the very foundations of that class division. Revanchist attacks on trans people are at their heart a move by the ruling classes to reassert control over this class antagonism. Because of this, trans people have a key role to play in terms of waging class war against the bourgeoisie and establishing a dictatorship of the proletariat, and every revolutionary must see the need to combat revanchist attacks on, and struggle for democratic rights for, trans people, not just for the sake of saving and improving the lives of trans people themselves (although that should also be important to us in its own right), but also as an indispensable part of waging class struggle around the key contradictions in our society.

In addition to being scapegoated in social conflicts and subjected to revanchist attacks, trans people also undergo a process of proletarianization that is uniquely shaped by the oppression they face as trans people. This is not to say that all trans people are proletarians (anyone who has met a trans gentrifier from some midwestern suburb in Maria Hernandez Park knows that’s not the case), or that trans people are a class in and of themselves. Rather, the point is that the social oppression of trans people results in an economic process of dispossession that is experienced to some degree by trans people of all income levels and class backgrounds simply due to the fact that they’re trans, although the degree to which trans people are subjected to this dispossession is certainly conditioned by their class background, in addition to other social factors. For example, due to the extreme degree of oppression that trans people face in many parts of the country, especially in rural, southern, and midwestern areas, many trans people are faced with the choice to either leave their homes and migrate to a region where trans people are more accepted, or face what will likely be an unhappy life and early death due to the often-fatal conclusions of trans oppression, such as suicide, drug addiction, hate crimes, and domestic violence. As a population, trans people are therefore subjected to forced migration en masse. And that’s only speaking of migration within the US—it would be an oversight not to also include the trans people from around the world who are forced to emigrate in order to escape oppression and persecution in their countries of origin. Forced migration subjects trans people to conditions of economic precarity when they find themselves having to establish themselves in an unfamiliar place, without social ties or a support network, often without papers that reflect their identity, if they have papers at all. The lack of life continuity and lack of support resulting from forced migration forces trans people into highly exploitative labor and downwardly mobile class positions.

Another aspect of the proletarianizing effect of the oppression of trans people is the impact that being categorically excluded from the nuclear family has on trans individuals. This exclusion comes in many forms: being disowned by their family of origin; choosing to be estranged from their family of origin; the forced migration described above causing strain on their family ties; infertility, dysphoria around reproduction, trauma, or cultural norms making it difficult, impossible, or undesirable for trans people to create their own nuclear family; etc. The vast majority of trans people can relate to the feeling of having to choose between family relationships and basic human dignity, so even those who aren’t forcibly expelled from their family, and who have some agency in deciding the degree to which they’re involved with their family of origin, still feel the impact of the powerful social forces that exclude trans people from full participation in the nuclear family. As a result, trans people can’t take advantage of the full economic benefits of the nuclear family: for example, they often can’t stay with their family to save up money, even if they might want to; they are more likely to be excluded from any ongoing financial support or inheritance if they’re from a family with disposable income or property; and, more generally, when almost everyone else in society relies primarily on their family for support of any kind, whether for a medical crisis, emotional difficulties, legal problems, childcare needs, or anything else a human being might need support for, trans people are left having to figure shit out for themselves. This is not only more expensive in any particular situation, but also results in an overall condition of extreme economic and social precarity for trans people who lack the basic safety net that the majority of society takes for granted.

When the economic disadvantages trans people already face due to forced migration and exclusion from the nuclear family are combined with other social factors that disproportionately impact trans people, such as lack of formal education, immigration status, a criminal record, employment discrimination, addiction or mental illness, and the inability to “pass” as cisgender, many trans people are outright excluded from the formal economy altogether. The exclusion from the formal economy and the nuclear family is a triple dispossession that can be understood in terms of Federici’s conceptualization of the oppression of women as a “double dependence: on employers and on men” (97) of “proletarian women who were as dispossessed as men but, unlike their male relatives, in a society that was becoming increasingly monetized, had almost no access to wages” (75). As discussed above, when the first class division between men and women emerged and the oppression of women was imposed across Europe, women underwent a double dispossession: the first dispossession occurred when proletarian women, like all of the European proletariat at the time, were dispossessed of access to the commons and therefore of any means of subsistence other than their own labor-power. This first dispossession forced proletarian men to sell their labor in exchange for subsistence wages, but the second dispossession that affected women exclusively, the new gendered division of labor, deprived proletarian women of even the ability to sell their labor, forcing them to carry out reproductive labor for men for free. Proletarian trans women today are subject to a third dispossession due to being excluded from not only the formal economy, but also the nuclear family, the basic unit of capitalist economic relations. They are locked out of both productive and reproductive labor, and as a result, this leaves them with no means of survival except to sell their own bodies; they become the commodities.

Due to this triple dispossession, many proletarian trans people (especially, but not exclusively, trans women) are forced into the sex trade, and, due to discrimination against trans people, especially into the most dangerous and undesirable forms of sex work, where they are subject to trafficking, rape, physical abuse, theft and extortion, and murder. Ask any trans girl who’s had to work the street or do full-service with johns she found on apps like Grindr, and she’ll tell you story after story of narrowly escaping rape or murder, as well as many stories where she wasn’t able to escape, and she was subject to extreme acts of violence and degradation. Some of the worst things anyone could imagine one human being doing to another are a nearly inevitable daily reality for trans sex workers. Because all in-person sex work requires direct contact with johns, these horrible experiences are nearly inevitable for trans people who rely on sex work for survival. The porn industry is another avenue for trans people to survive when they’re locked out of the formal economy, where they’re subject to many of the same conditions. The tranny porn14 industry especially preys on trans people who are early in their transition, using their insecurities, social isolation, self-hate, and dysphoria (in addition to their economic desperation) in order to manipulate them into making porn that degrades, fetishizes, and dehumanizes them. At best, trans sex workers can count on getting no help from police when they’re raped, brutalized, trafficked, or robbed. At worst, they can expect to be beaten by police or coerced into sex acts, and criminalization that ends in repeated arrests and often prison time. While prison is hell for everyone sent there, it’s especially hell for trans people, who are preyed on by guards, gangs, and pimps, and subject to sexual and other violence. Aside from survival sex work, or often in addition to it, trans people are often forced to beg for money on the internet in the absence of formal employment, soliciting donations from their networks via platforms like Gofundme, Venmo, and Cashapp. Not only is that not a sustainable or dignified way to live, but those platforms are also infamous for locking or disabling accounts arbitrarily, which means that people who rely on them for survival can have thousands of dollars stolen from them in an instant.

The triple dispossession of proletarian trans women and the commodification of their bodies goes beyond sex work and affects every area of life. For example, for these women, finding a safe place to live; being protected from transmisogynist violence; and achieving any degree of economic, emotional, and social stability all depends on finding a man who will take care of them, which in turn hinges on their ability to give their bodies to a man (or: the value of their bodies as commodities) in exchange for certain benefits that enable their survival on a basic level. This might sound cynical—it’s not to say that proletarian trans women have no agency in defending themselves against male violence and surviving outside of their relationships to men, or that the best they can hope for are transactional romantic relationships. They’re much more than someone’s sex toys. However, the reality for the vast majority of proletarian trans women is that they have been dispossessed of any means of survival under capitalism other than selling their own bodies, and this economic position naturally cuts across every aspect of their lives.

The economic impact on trans people of forced migration, exclusion from the formal economy, and exclusion from the nuclear family is a downward mobility across the board: for trans people from almost any class background, their ability to take advantage of any opportunities they might have had because of their class background are limited due to the oppression they face as a trans person. Trans people from proletarian backgrounds are hit the hardest, as they’re more disposed to face these forms of dispossession in the first place, and they have less of a safety net to fall back on when these forms of dispossession compound. This creates an uneven distribution of dispossession among trans people, and has resulted in a sharp class division among trans people.