Organization of Communist Revolutionaries (US), International Department

May 1st, 2025

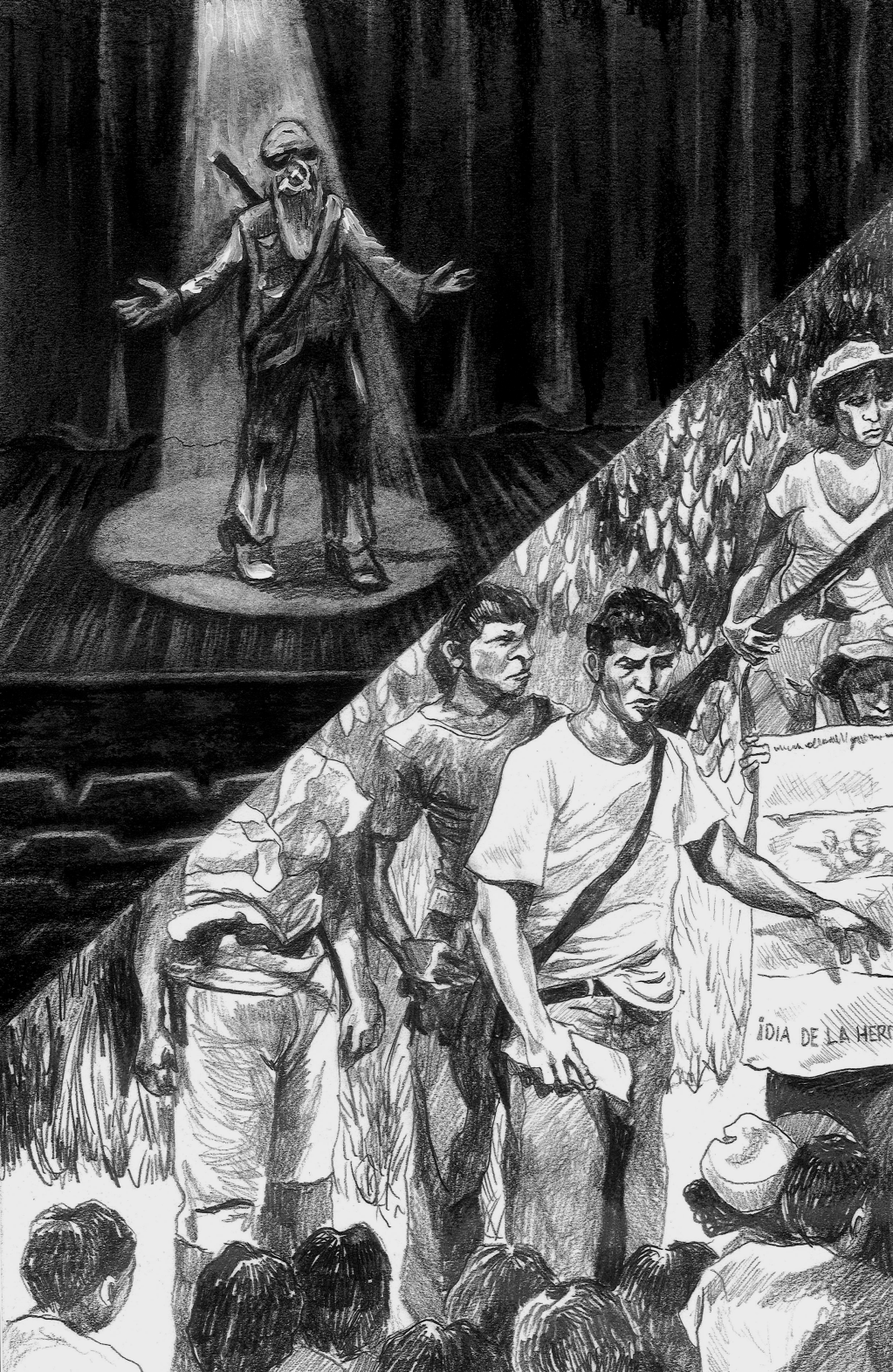

Let us start with a stark assessment: there is no international communist movement today. There are lots of organizations around the world who call themselves communist, socialist, revolutionary, Marxist-Leninist, Maoist, etc., but most of them are complete garbage. They use the monikers, terminology, and aesthetics of the communist tradition in order to promote dogmatism, reformism, capitulation, and, most of all, themselves. Some are part of the long tradition of revisionism and can trace their lineage back to one or another historical betrayal of communist principles and the masses, such as Trotsky’s attempts to sabotage the socialist transition to communism in the Soviet Union or those who embraced the 1976 counterrevolutionary coup in China that overthrew socialism and brought a new bourgoisie to power led by Deng Xiaoping. Others are more recent additions, usually people who spend a lot of time posturing on the internet but no time among the masses. Whatever particular form they take, those who claim communism for reasons other than dedicating their lives to revolution and the masses are doing the bourgeoisie’s work for them, and deserve the kind of treatment Sendero Luminoso gave to their counterparts in 1980s Peru.

When we clear that garbage from view, we can see that there still are genuine communists dedicated to making revolution in some parts of the world, but mostly in relatively small organizations that are not united into something that could accurately be called an international communist movement. There are a few places where Maoism has a strong legacy and where revolutionary struggle continues to be waged under communist leadership today to greater and lesser extents, in particular Turkey, South Asia, and the Philippines. But there is no international organized forum for bringing the world’s genuine communists together, nor is there any force currently able to lead the development of such a forum. We write this document to address why that is the case, in the hopes of finding comrades around the world who want to transform this situation. At the end of this document, we extend an invitation to such comrades to initate discussion and debate aimed at beginning to rebuild an international communist movement.

The RIM’s demise and the lack of RIMist principles today

From 1984 up until the mid-2000s, there was an ideogically coherent and organized international communist movement in the form of the Revolutionary Internationalist Movement (RIM). The strengths and achievements of the RIM included:

- Regrouping genuine communists around the world, with participant parties and organizations in both the oppressed and imperialist countries, after the revolutionary storms of the 1960s had subsided and socialism had been lost in China with the 1976 counterrevolutionary coup. Given the widespread demoralization and disorientation among revolutionaries, as well as strong capitulationist winds, of the 1980s, the founding of the RIM on firm communist principles was a great achievement in and of itself.

- Synthesizing the essential lessons, positive and negative, of the history of the international communist movement and the experience of proletarian dictatorship and pioneering an approach to summing up our tradition that firmly upheld revolutionary principles while being deeply critical of our shortcomings and mistakes, in opposition to the kind of religious and dogmatic ways of thinking that have too often seeped into our tradition.

- Upholding, defending, and developing the advances in communist theory and practice led by Mao Zedong, including in how to advance the socialist transition to communism through class struggle, and systematizing their universal significance for contemporary and futures waves of communist revolution.

- Publishing an international journal—A World To Win—for over twenty years that brought communists around the world into discussion and debate, published intellectually rigorous articles taking up historical summation and contemporary political analysis, and promoted and drew lessons from revolutionary struggles around the world.

- The rapid advance, up to the point of contending for state power, of two innovative revolutionary people’s wars, first in Peru and then in Nepal, led by RIM participants the Communist Party of Peru and the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist).

- Providing leadership to international campaigns supporting revolutionary struggles and defending imprisoned revolutionaries, most especially the campaign to defend the life of Chairman Gonzalo after he was captured and imprisoned by the Peruvian bourgeois state.

There is much more to sum up about the RIM, and to that end, the journal Going Against the Tide recently published a volume titled The Legacy of the Revolutionary Internationalist Movement, which includes the RIM’s 1984 founding Declaration and several articles that contribute to summing up its legacy. We hope other comrades around the world will further contribute to summing up the RIM. In any event, as we see it, the principles and practice of the RIM are the foundation for any attempt to rebuild the international communist movement today. The RIMist approach to unity–struggle–unity and the RIMist interpretation of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism are qualitatively more advanced, on an international level, than anything else during its time or since. The RIM cannot be repeated as it was, and we are not advocating simply trying to pick up where it left off without assessing its weaknesses or building on its approach. But the Organization of Communist Revolutionaries is decidedly RIMist in our orientation, with the RIM Declaration a foundational document for our development.

Unfortunately, the RIMist approach has not been taken up by many others in the world since the RIM’s collapse as an ideological and political center and organizational form in the mid-2000s. Even during the RIM’s existence, its ideological and political strengths faced challenge from without and from within. Some RIM participants, such as K Venu’s Central Reorganization Committee, Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist), outright capitulated in the face of the international anti-communist onslaught of the 1980s and 90s. As the international bourgeoisie propagandized about the purported horrors of communism and proclaimed the collapse of the (by then state-capitalist) Soviet Union as proof of the superiority of free markets and democracy, K Venu and other erstwhile Maoists decided to embrace bourgeois-democracy and renounce communist revolution and proletarian dictatorship, often hoping for a parliamentary position in exchange for their betrayal of the international proletariat.

More widespread than capitulation, however, was gradual decline, growing disagreements, and organizational disintegration. In the RIM’s first decade of existence, several of its participant organizations faded into irrelevance or went out of existence, and too often without any public summation. Strong differences with RIMist principles emerged from some RIM participants soon after the 1984 Declaration was published. In Turkey, a strong bastion of Maoism, the communist movement split into different party centers, with some upholding RIMist principles and others moving in revisionist directions.

The bigger problem within the RIM, however, was not the fade away of—or wrong direction taken by—some of its participants, but a growing dogmatic streak in contrast to the best of its principles and practice. This dogmatic streak has its roots in the intellectual and analytical weaknesses of the Maoist movement of the 1960s and 70s and the failure to develop intellectual methods and intellectual work that could remedy those weaknesses. The RIM was far better than others in the Maoist tradition in addressing those weaknesses, but it was still plagued by them. Within the RIM, the dogmatic streak became stronger in the wake of the capture of Chairman Gonzalo and the setback in the revolution in Peru. Some within the RIM, especially in Europe, responded to that setback with what can only be described as religiosity. They viewed Gonzalo and the people’s war in Peru as the Second Coming that promised the Rapture—a “century of people’s wars” that would lead in a straight line towards the Heavenly Kingdom of communism. With this religious thinking, they lost the ability to think dialectically and deal with the contradictions that are part of the revolutionary process, and promoted an increasingly dogmatic interpretation of Maoism full of false optimism but lacking in materialist strategic confidence.

The RIM collapsed in the mid-2000s as a consequence of growing disunity among its participants and the growing dogmatism within it. The final nail in the RIM’s coffin was the capitulation of Prachanda and other leaders of the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), precisely when the revolutionary people’s war in Nepal had reached its greatest height and the challenge of seizing state power was most directly and immediately on the agenda. The end of the people’s war in Nepal and the public renunciation of communist principles and objectives by some of its leaders was a blow that the RIM could not recover from given the disunity within it.

As and after the RIM collapsed, those of its participants who did not outright and openly capitulate moved in more or less three different directions, which we call Avakianism, the first church of PPW universalism, and good old Maoism. The Avakianists answered the dogmatic streak in the RIM by insisting that the “new synthesis” (or, more recently, “the new communism”) developed by Bob Avakian, the Chair of the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA, an important RIM participant since its inception, was a dividing line that the whole international communist movement must embrace. That insistence has only led to an additional form of dogmatism, with the Avakianists unable to answer the strategic challenges of advancing the revolutionary movement in their own countries and becoming increasingly politically irrelevant.

The first church of PPW universalism is a mainly European trend of former RIMists and others that has taken dogmatism and irrelevance in the furthest direction. They proclaimed the strategy of protracted people’s war developed by Mao that guided the Chinese Revolution to victory to be universally applicable in all countries, but have failed to ever demonstrate—or even tried to demonstrate—that universality in practice. They issue lots of idiotic statements to make themselves feel important, but have nothing to show for themselves as far as revolutionary work among the masses.

By good old Maoism, we mean those former RIMists and others who imagine we can make revolution simply by mechanically applying what worked in the past and through fidelity to Marxism-Leninism-Maoism. The good old Maoists might be genuine in their desire for revolution and dedication to the masses, have real and sometimes ongoing experience in revolutionary struggle, and still uphold revolutionary principles. But they have failed to apply those principles to advance proletarian revolution in the present. Their Maoism has become increasingly ossified, and their statements have become increasingly dogmatic and out of touch with reality, as exemplified by the Maoist Road blog and the journal Two Line Struggle. The latter has spent years polemicizing against the second church of PPW universalism (which we will explain below)—polemicizing that is largely irrelevant to the advanced masses—without producing any real contributions to revolutionary theory or summation of revolutionary practice.

During the RIM’s existence, there were some genuine revolutionary parties and organizations rooted in Maoism who remained outside of the RIM, and perhaps some other (small) ones have been formed since the RIM’s demise. The two most significant ones in the former category are the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and the Communist Party of India (ML-PW). The latter merged with other Maoist organizations, with the assistance of the RIM, to form the Communist Party of India (Maoist) (CPI(Maoist)) in 2004, but chose not to join the RIM. Both the CPP and the CPI(Maoist) have been leading revolutionary people’s wars for decades, and we have great respect for them as genuine revolutionary parties. However, neither currently has the capacity, ideologically, politically, and organizationally, to lead the process of rebuilding the international communist movement (ICM).

We will address the reasons the CPP cannot play such a leading role below. The revolutionary struggle led by the CPI(Maoist) reached impressive heights in the mid-2010s in the Dandakaranya forest region, with the Adivasi populations as its principal mass base. The Indian bourgeois state responded with fierce repression in an encirclement and suppression campaign. The CPI(Maoist) has stood heroically in the face of this repression, refusing the Prachanda path of capitulation, and we extend them a warm red salute for the strong example they have set. Besides repression by a powerful repressive state apparatus, the CPI(Maoist) also faces the challenge of how to develop revolutionary strategic doctrine in an India very different from China in the 1930s and 1940s, with a growing urban population and a large informal proletariat that lives, for the most part, in massive slums, as well as changing conditions of feudal and capitalist exploitation in the countryside, not to mention the recent rise of Hindu fascism to political power. There is much theoretical and practical work to be done to address these challenges, and unfortunately few comrades around the world besides the CPI(Maoist) are practically engaged in these challenges.

Pageantry and the meaningless of the moniker Maoist today

Since the demise of the RIM and the inability of any communist party, or group of communist parties, to play a vanguard role in rebuilding the international communist movement, there has been a disturbing growth of what can only be called pageantry rather than plotting world proletarian revolution. A variety of international organizations and international gatherings have been convened that issue statements, often bombastic in substance and style, publish analysis that offers little insight into the motion and development of capitalism-imperialism or the pathways to overthrow it, and compete over whose rhetoric is most revolutionary. More than anything else, this culture of pageantry serves to bolster its participants’ sense of self-importance. None of the existing international organizations and gatherings among so-called communists are forums for plotting the advance of world proletarian revolution, as they have no basis of principled unity from which to do so.

The most comical example of the kind of pageantry we are criticizing is the International Communist League (ICL). It brings together adherents of the second church of PPW universalism, who distinguish themselves from the first church by their age—most started calling themselves Maoists in the 2010s—and by their complete lack of connection to the communist tradition they claim, including the Communist Party of Peru under Gonzalo’s leadership. These are online “communists” who use the aesthetics and dogmatic aspects of our tradition to carve out niche identities and subcultures on social media and internet forums. The ICL’s statements all sound like text generated by an artificial intelligence bot that has been programmed to write dogmatic nonsense—ChatMLM? Declaring themselves an international communist organization is an absurd attempt to posture as something serious, and no one should take the ICL seriously. We feel embarrassed even mentioning them in a document about rebuilding the international communist movement, but the subjective conditions today have reached such a low that it has become necessary to devote a paragraph—and no more than that—to telling the ICL to stop laying claim to the communist tradition that millions of people have fought and died to continue.

Other supposedly communist international formations might be slightly less comical than the ICL, but either do not contribute to or stand in the way of unity based on revolutionary principles and providing a forum for strategizing for revolutionary advances. The International Coordination of Revolutionary Parties and Organizations (ICOR), founded by the Marxist-Leninist Party of Germany and and led by its eclectic, revisionist politics, is a classic example of “all unity and no struggle,” imagining that the problem in the ICM is mainly one of disunity that can be solved without any ideological struggle. Besides avoiding discussions of cardinal questions of revolutionary principle and strategy, ICOR’s main activity seems to be issuing dull statements on all manner of international issues. The level of unity in ICOR is so low that individual members have the option to sign or not sign on to such statements, and even when signing on to qualify their signatures with various political objections, a firmly bourgeois-democratic practice.

Beyond its worst examples, the culture of pageantry is pervasive among virtually all international forums of so-called communists and Maoists, with even some of the real ones getting sucked into it. Its distinguishing features are:

- A lack of principled unity and struggle over questions of ideological and political line. Instead, there is either centrism and eclectics by way of “all unity and no struggle” or narrow, obnoxious polemicizing for performative purposes of proving who is the most revolutionary.

- No intellectual life of any value or interest, no insightful, fresh analysis, just a lot of dogmatism and blustery rhetoric.

- False optimism in the advance of proletarian revolution based on bombastic declarations about capitalist crisis, multipolarity, and fictitious or exaggerated people’s movements on the rise.

With pervasive pageantry on the international stage and plenty of dogmatism to go around, and with the addition of social media as a means to declare political ideologies as subcultural identities, the moniker Maoist has become mostly meaningless today, at least in the imperialist countries. Rhetorically, the moniker Maoist no longer has the discursive power to signify fidelity to a set of revolutionary principles and association with real-world revolutionary movements. Instead, at least in the imperialist countries, it mostly signifies membership in an obnoxious subculture of online Leftists. None of that changes the revolutionary principles and practice that made Maoism in the course of the Chinese Revolution and the socialist state established by it and were taken up by genuine communists around the world. But it does mean that regrouping today’s genuine communists cannot be done simply by gathering together those who declare themselves Maoists, as many such people need to be told to get the fuck out of the way.

What words are used to distinguish genuine communism from those who claim its legacy for self-serving purposes will have to be determined by what monikers spring up from the advance of revolutionary movements. The history of the communist tradition includes the invention of terminological distinctions between genuine revolutionaries and revisionist betrayal: from social-democrat to communist, Marxist-Leninist, and Bolshevik, and then to revolutionary communist and Maoist. Faced with this terminological dilemma after Prachanda’s betrayal of the Nepalese revolution, Kiran’s organization in Nepal called itself the Communist Party of Nepal (Revolutionary Maoist).1 On the surface, the appellation “Revolutionary Maoist” might sound ridiculously redundant, but when you consider the distinction being made with the party of capitulation it split from, it becomes essential. The point here is that we are not concerned with terminology, but with principles, with drawing lines of demarcation between communism as a revolutionary tradition against any attempts to use it for purposes other than revolution. We will fight over principles, and sometimes that might mean fighting over words, but the latter divorced from principles and practice becomes meaningless.

When it comes to Maoism, we will argue for a RIMist interpretation, for the conception of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism that is articulated in the RIM Declaration, without treating it as frozen in time. Part of the reason for the increasing meaninglessness of the moniker Maoist is that even genuine would-be communists donning it lack RIMist clarity on Maoism itself. To them, we suggest studying the RIM Declaration and the best articles from A World To Win magazine, but not divorced from applying the principles you can learn from those documents in the real world. To mean anything good, Maoism has to be internalized and put into practice, applied and developed to advance the revolutionary struggle, and defended and further developed throughout the twists and turns of that struggle.

Let the Lavas flow: the opportunist line of the Communist Party of the Philippines on internationalism and international relations

Maoism has meant something good, something revolutionary, in the Philippines from the foundation of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) in 1968 up through the present. The founding document of the CPP and of the people’s war it has led, Jose Maria Sison’s Philippine Society and Revolution, spends many pages polemicizing against the Lavas clique in the Philippines that had betrayed communist principles and abandoned revolution. Despite the relative irrelevance of the Lavas clique to the new generation of revolutionaries that joined the CPP in its early days, Sison evidently considered it essential to delineate Maoist principles from Lavas revisionism, a delineation that made possible the formation and growth of the New People’s Army.

Since its foundation, the CPP has at times been plagued by vacillations on the Maoist principles argued for in Philippine Society and Revolution. When a new bourgeoisie came to power in China in 1976, the CPP was not quick or consistent in condemning the counterrevolutionary coup, and its views on capitalist restoration in the Soviet Union and China have not always been crystal clear. In the 1980s, CPP leadership softened its view of the bourgeoisie in power in the Soviet Union in hopes of getting arms and political support from them, when the Soviet Union was buttressing some national liberation struggles in Latin America and Africa as part of its imperialist rivalry with the US.

Those and other vacillations were not merely problems in theory or formal line, but had considerable negative impact on the revolutionary struggle in the Philippines, contributing to missing potential opportunities for the conquest of state power in the 1980s when the Marcos regime collapsed. To its great credit, CPP leadership recognized these errors and launched the CPP’s Second Great Rectification Movement in 1992, which put the CPP decisively on the revolutionary road. A further review of the line of the CPP and the trajectory of the revolutionary people’s war it leads is beyond the scope of this document. We have been reading about the CPP’s current rectification movement and hope that its outcome results in further advances for the revolutionary struggle in the Philippines.

What needs substantial attention here, and substantial criticism, is the CPP’s line and approach to internationalism and international relations over the last two decades, which has had an increasingly negative impact on the prospects for rebuilding the international communist movement. That line and approach has been guided by centrism, eclectics, and pragmatism, making a principle out of refusing to distinguish between revolution and revisionism, the Maoist model of the socialist transition to communism vs. other concepts of socialism, and the strategic objectives of communist revolution vs. necessary tactical and diplomatic maneuvering in service of those objectives. It has led the CPP to increasingly prop up all sorts of opportunists, revisionists, Trotskyites, and grifters around the world, without, from what we can see, any tangible benefits to the revolutionary struggle in the Philippines. And, to put it mildly, it has generated lots of reformism and dogmatism among people outside the Philippines inspired by the political line of the CPP and the revolutionary struggle it leads.

The centrism, eclectics, and pragmatism we are criticizing is articulated in the CPP’s 1994 document Guidelines on International Relations of the Communist Party of the Philippines. In it, the CPP rejects the RIM as a concept without actually naming the RIM, favoring unity by way of accumulating points of agreement (an anti-Maoist conception) rather than unity forged through a process of principled debate and line struggle (the Maoist conception of unity–struggle–unity) with a firm rejection of revisionist betrayal of communist principles. Indeed, the CPP does not make upholding Mao’s historic struggle against revisionism a dividing line, expressing openness to a variety of “Marxist-Leninist” parties, i.e., revisionist ones. The CPP suggests two different kinds of relations, communist bilateral relations and anti-imperialist political solidarity, but does not and has not made a clear distinction between the two.

Judging by the CPP’s practice, this 1994 document is still its line, and its eclectics and centrism on internationalism and international relations have only continued and gotten worse. Furthermore, the failure to distinguish between revolution and revisionism is joined, in more recent documents by the CPP, with talk about “countries assertive of national sovereignty and socialist aspirations.”2 The problem with this formulation is not that it doesn’t capture an important contradiction in the world today, between such countries and imperialist powers, especially but not only the US, but that it takes a centrist and eclectic position on the question of what class rules such countries and towards what ends. The CPP fails to distinguish between the Maoist principle and practice of socialist self-reliance and the national sovereignty desired by bourgeois developmentalist regimes. We have no clear idea of what they mean by countries assertive of “socialist aspirations,” a term that seems to encompass all kinds of different ideas of socialism rather than help to clarify the Maoist conception of the socialist transition to communism, which is established by the seizure of power, not the assertion of aspirations.

Manifestations of the CPP’s centrist and eclectic line on internationalism and international relations are evident in the practice of organizations and events outside of the Philippines that are inspired by and carrying out that line. For example, the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) recently held three international theoretical conferences that brought together various political organizations to discuss imperialism and war (in 2023), the economic crises of imperialism, and national liberation from imperialism (in 2024). While a few genuine revolutionary forces contributed to these conferences, many revisionist, counterrevolutionary, and downright repugnant forces were invited to participate and even given platforms from which to present their poison. For example, the Belgian Workers Party, a longtime champion of capitalist restoration in China, took part, and was not thrown out after heckling Maoist analysis. Consequently, these international conferences sponsored by the NDFP have miserably failed to provide a forum for genuine communists to plot the advance of world proletarian revolution. They have been another form of pageantry, giving their participants a sense of self-importance by way of association with the revolutionary prestige of the NDFP. The papers published from these conferences occasionally make a few interesting points but fail to galvanize revolutionary forces internationally around key dividing lines or creatively analyze the challenges before such forces. At best, the NDFP’s international conferences have muddied the waters between revolution and revisionism, and at worst they have given legitimacy to outright counterrevolutionaries. Needless to say, the OCR has not participated in any of these conferences.

Another international effort inspired by the Philippine revolution, the International League of People’s Struggle (ILPS), formed in 2001, has similarly brought together genuine revolutionaries, Trotskyites and revisionists, and everything in between under its banner. Not surprisingly given the unprincipled and pragmatic unity of its participants, the ILPS has failed to advance international people’s struggles, as a collective entity playing no advanced role in the worldwide mass movement against the US-Israel genocidal war on Gaza and even running cover for opportunists who worked to hold that movement back from moving in a more militant direction. Young activists in North America and Europe inspired by the Philippine revolution who join up with the ILPS are only getting trained in liberalism (while, ironically, being encouraged to study Mao’s essay Combat Liberalism) and even capitulation (by way of using international solidarity work to give up on revolution in their own countries), squandering their revolutionary potential. The broad unity of a formation like the ILPS of course need not and should not be adherence to communist principles, but allowing opportunists into the mix and practicing pragmatism has rendered the ILPS incapable of providing a broad mass of activists with positive experience in struggle or of playing a positive leadership role in mass movements.

The larger conclusion we must draw from both the CPP’s line on internationalism and international relations and the practice that it inspires around the world is that the CPP’s centrism, eclectics, and pragmatism, its platforming of opportunism internationally, is obstructing the development of revolutionary forces outside the Philippines and stands in the way of rebuilding an international communist movement. It makes perfect sense that as the revolutionary movement in the Philippines advances, it might make tactical and diplomatic alliances with various governments and political forces outside the Philippines that can help break through international encirclement and suppression and provide diplomatic and even material support to the Philippine revolution. However, alliances with lots of pathetic opportunist forces around the world, who can at best organize boring protests and produce discourse dripping in dogmatic drivel, can only tarnish the reputation of the CPP and strengthen incorrect lines among its followers. Beyond its potential negative consequences for the Philippine revolution, the failure to distinguish between revolutionary and counterrevolutionary forces, and propping up the former against the latter, around the world can only impede world proletarian revolution.

Ironically, the CPP absolves itself of the sins of centrism by projecting its international work as centrism, claiming that the politics of organizations outside the Philippines are not its business to take positions on and publicly abdicating responsibility for rebuilding the international communist movement. Yet as everyone knows, the CPP has taken on an increasingly assertive political role internationally, and as the communist party leading the largest revolutionary struggle today, it cannot but have an outsized impact around the world. When it comes down to picking sides internationally, evidence suggests that the CPP chooses to align with revisionists and opportunists over genuine revolutionaries—as is always the case, centrism and eclectics leads to revisionism. Unless and until it repudiates centrism and eclectics and draws a clear line of distinction between revolution and revisionism internationally, and between revolutionary strategic objectives vs. tactical and diplomatic maneuvering, the CPP’s international impact will be principally negative, holding back the development of revolutionary forces outside the Philippines and preventing the principled unity necessary to rebuild the international communist movement. Simply put, the CPP cannot be a vanguard in rebuilding the international communist movement, and communists outside the Philippines will have to develop revolutionary forces against its influence.

Finally, we must end our critique by speaking bluntly to the CPP: our mission is to make revolution in the US, and actions that prop up counterrevolutionaries and impede the development of the subjective forces for revolution in the US cannot be tolerated if we are to have a shot at bringing down US imperialism. The NPA has set a correct example for how to deal with counterrevolutionaries in the Philippines, and we can only hope to someday live up to that example in our country.

Semi-dogmatic conditions in the oppressed countries and fully developed dogmatism in the imperialist countries

Taking a global view of communist forces and would-be communists around the world, we have to perform a negation of the negation of our above criticisms of the CPP. Whereas the CPP has failed to distinguish between Maoist principles and revisionist betrayal internationally, and has practiced lots of empiricism while doing well at making empirically-grounded analysis, most genuine and would-be communists around the world have been turning Maoist principles into dogma and failing to develop those principles through empirically-grounded analysis of contemporary conditions.

Among communists in the oppressed countries, prevailing semi-dogmatic conditions have hindered their ability to deal with new realities and make strategic innovations accordingly. Many repeat decades-old analysis concerning semi-feudal and semi-colonial conditions without taking account of postcolonial transformations of oppressed countries, such as the integration of national bourgeoisies and production processes into global capitalism, mass rural to urban migration, the growth of slums, and the development of manufacturing and new production relations and industries. The two (RIMist) Maoist-led people’s wars that advanced the furthest towards seizing state power in the last fifty years—in Peru and Nepal—did so precisely by confronting these new conditions and transforming the strategy of protracted people’s war, with the Communist Party of Peru turning the slums of Lima into base areas and making the capital city into a central theater of warfare. More analysis remains to be done of how oppressed countries have changed over the last fifty years, but it is undeniable that the conditions in which Mao led the Chinese revolution to victory no longer exist in the way they did in the 1930s and 40s.

Mao’s analysis of classes and conditions in pre-1949 China and strategy of protracted people’s war and new-democratic revolution was an innovation, a creative development of Marxism-Leninism, not a dogma to remain frozen in time and to be mechanically applied a century later. This does not mean that armed struggle is not possible in oppressed countries and that aspects of Mao’s strategy do not still apply. But the masses need communists who are willing to confront contemporary realities and can be creative thinkers in forging revolutionary strategy, and such communists are in short supply today.

On the other hand, the changed conditions in the oppressed countries are sometimes used as an excuse for not starting armed struggle. Indeed, many of those who talk the most about how oppressed countries today are no longer principally characterized by semi-feudal and semi-colonial conditions, even if their analysis is substantially correct, are the same ones who renege on armed struggle. An international communist movement worthy of the name needs the right synthesis of firm revolutionary determination to start armed struggle and carve out red base areas wherever it is possible to do so and intellectual sophistication and creativity in analysis and strategy to guide that armed struggle.

What makes the prevailing subjective conditions in the oppressed countries semi-dogmatic rather than fully dogmatic is that many genuine communists in those countries are practically engaged in the struggles of the masses, sometimes including via armed struggle and even local red political power. Integrating with the masses, applying the mass line, and leading class and armed struggle against the enemy keeps those communists in touch with reality and forces them to deal with the real challenges of making revolution, even if their theory, analysis, and strategic doctrine lags behind their practice and holds back that practice from advancing further. In the imperialist countries, by contrast, the older generation of Maoists has largely lost touch with the masses and with the practical struggle for revolution, while the new generation of would-be Maoists for the most part have yet to get in touch with reality, coming to Maoism via the internet and obsessing over debates within the Left rather than the conditions and struggles of the masses. Consequently, the prevailing subjective conditions among so-called Maoists in the imperialist countries today are fully-developed dogmatism.

We have already identified the dogmatic trends among the Maoist old guard in Europe above, and we have previously written plenty about dogmatic “Maoists” and Leftists more generally in North America,3 so here we will focus on the new generation of would-be communists in Europe. What stands out about these would-be communists is two problems: (1) Whatever they call themselves and whatever theory they have studied, they lack clarity on MLM principles, and the RIMist understanding of MLM seems not to be in the thinking of these European “Maoists” at all. (2) There’s glaring inexperience when it comes to integrating with and organizing the masses, and not much sophistication or even interest in concrete analysis of contemporary conditions.

Both of these problems are completely understandable given that this is mostly a young crowd; the lack of an international communist movement with an ideological, political, and organizational center to give them guidance; and the misleadership of the CPP internationally. But with perhaps a few exceptions, these would-be communists in Europe seem to lack the determination or even the desire to overcome these objective difficulties. Rather than being humble about their inexperience, integrating with the masses, and studying theory in relation to practical problems, they spend lots of time on the internet and in self-contained bubbles of Leftist discourse. They make Maoism a subcultural identity rather than a transformative force in the real world.

The worst expression of what we are criticizing in Europe can be seen in the aesthetics of and culture around the publisher Foreign Languages Press (FLP-Europe). FLP-Europe publishes important documents from and about the Chinese revolution and from Maoists and revolutionaries around the world—mostly documents from decades ago, and studiously avoiding RIM documents. They also publish garbage, such as the attempts to marry MLM with postmodernism written by Canadian hipster Joshua Moufawad-Paul, who has tried to anoint himself as a philosophical expert of Maoism by producing loads of psuedo-intellectual nonsense, engaging in idiotic, insular Leftist social media discourse while sharing his bad tastes in music and artisanal mustard recipes, and never integrating with the masses.

Even the revolutionary texts that FLP-Europe publishes, however, come wrapped in dogmatic packaging, literally and metaphorically. On the literal end, and at the risk of sounding petty, this so-called publisher seems not to have noticed that there are margins around the text of almost all books but theirs, and they gravitate towards the most ugly choices of font imaginable. They have rejected the better artistic traditions of the international communist movement in favor of dogmatic aesthetics. Beyond aesthetics, FLP-Europe promotes a culture of book worship, of performative study of communist theory for the purposes of scoring points on social media and in debates among insular circles of Leftists. Them and their followers revel in obscure documents and cannot discern line or apply communist theory to changing the world. We have yet to hear of a single example of an individual or group using their study of FLP-Europe publications (and the sense of identity that goes with doing so) to go to the masses and organize class struggle. Worst of all, FLP-Europe has the audacity to appropriate the moniker of the the great publishing house forged in revolutionary China for their own dogmatic purposes, inflating their sense of self-importance while doing a great disservice to the masses and to the communist tradition.

FLP-Europe also highlights the problem, among “Maoists” in imperialist countries, of looking to revolutions and revolutionaries in the past and in other countries—and all too often to feel good about themselves by association—rather than figuring out how to connect revolutionary politics with the masses in their own countries. In Europe, the only exception we know of to this trend over the last decade is the short-lived Jugendwiderstand (Youth Resistance) in Germany. Formed and disbanded in the 2010s, Jugendwiderstand quickly developed a reputation for combativity, getting into street brawls with Nazis, taking bold street actions in support of Palestine, being willing to go up against police repression, and throwing a few punches at Trotskyites too (the OCR extends a warm red salute for that last one). More than just militancy, Jugendwiderstand had a proletarian revolutionary character, and their revolutionary stand and energy connected with immigrant and proletarian youth, with creative agitation campaigns such as “don’t destroy yourself, destroy the enemy” aimed at getting youth off drugs and into the revolution. Unfortunately, repression brought Jugendwiderstand to a quick end, with the German state using the organization’s firm stand in support of Palestine to bring about false charges of antisemitism and making legal threats against its members, including to deport their families, and pressuring their employers to fire and blacklist them.

Undoubtedly, Jugendwiderstand had its share of weaknesses and mistakes, and some have criticized it for violence that verged on hooliganism and lumpen tendencies. We have yet to see a thorough summation of Jugendwiderstand, and we draw our information from more informal sources; we hope someone can provide a more comprehensive, critical, and accurate summation than we are able to (including pointing out if our characterization is incorrect in any ways). In any event, we uphold the overall revolutionary spirit and proletarian character of Jugendwiderstand, and we wish other would-be communists in Europe were much more like them. Whatever their mistakes were, they seem to us like the mistakes of youthful revolutionaries unprepared for intense repression and without the theoretical sophistication and training to go beyond their initial revolutionary activity when repression curtailed it.

The lesson to draw from today’s “Maoist” milieu in Europe, from Jugendwiderstand to those spending their time on the internet rather than brawling in the streets, is that integrating with the masses and dealing with the real challenges of making revolution is a necessary starting point for the development of communist cadre who can go on to form vanguard parties. And dogmatism in any form is an impediment to turning those would-be communist cadre into the sophisticated, creative thinkers that the masses need us to become if we are to develop the subjective forces for revolution in our own countries and contribute to rebuilding the international communist movement. Enough with the book worship, with the embarrassing polemics among online “Maoists,” and with performatively praising but never following the example of foreign and past revolutionaries. Get with the masses, get thinking dialectically, and let’s debate and discuss how we confront the challenges of making revolution in the present.

The OCR’s approach to developing international relations

With this document, the Organization of Communist Revolutionaries announces its intent to develop an international department for the purpose of forging relations with genuine communist parties and organizations around the world and contributing to rebuilding the international communist movement. At this point, our international department is more aspirational than existent, and will be brought to life through the process of developing dialogue and forging working relations with communists around the world. We take that process seriously, so from the start we eliminate all revisionists, Trotskyites, and other opportunists from the prospect of comradely relations, as well as those too mired in dogmatism to productively discuss how to advance proletarian revolution. And with potential comrades, we will not be going the route of pageantry. We are not looking to bolster ourselves through attachment—or, worse yet, being sycophants—to revolutionary movements outside our borders or through the practice of issuing bombastic international statements. Instead, we are seeking to initiate processes of discussion and debate, largely through private channels, that lead to collaborative efforts.

We believe that doing due diligence is essential for forging comradely relations. In other words, with any potential comrades, we will study their key documents carefully, assess their strategic approach and practice as best we can, and test out our relationship through working together on specific projects, such as interviews or other content for publication. The purpose of this due diligence is to base our relationships on ideological and political line, not on proclaimed fidelity to Marxism-Leninism-Maoism or one friendly conversation at an international conference. Having line differences within the parameters of firm revolutionary principles is fine, and can be productive if we debate those differences out. But it is only through clarity on line questions, including what differences exist, that we can productively collaborate.

Our starting point for entering into dialogue and collaborative efforts is RIMist MLM and the RIMist approach to unity–struggle–unity,4 along with the line documents our organization has published, most especially our Manifesto and our summation of the communist movement in the US. We put forward our documents not as dividing lines for the international communist movement, but as a way to understand the OCR and its line and as a productive point of departure for discussion and debate.

To revolutionary parties and organizations outside the US interested in establishing relations with the OCR, the first step is to contact us, either through our public email (ocrev@protonmail.com) or through a private channel if you can connect with us through non-public means. For well-established parties and organizations, we ask that your initial correspondence address the following questions:

- What is your assessment of the RIM and its Declaration?

- What do you see as the strategic challenges of making revolution in your country?

- What do you think of this document and any other OCR documents you have read?

- What documents of your organization should we read?

For new and less experienced organizations, such as groups of young revolutionaries diving into the class struggle but without the benefit of veteran comrades or years of experience, we ask you to address the following questions:

- How are you training yourselves in Marxism-Leninism-Maoism?

- What are you learning from the masses through your ongoing political work and integration with the masses?

- What do you see as the more promising political struggles in your country and how are you trying to relate to them?

- Within security considerations, what political work are you trying to undertake (i.e., there might be a general way to answer this question without revealing specifics)?

- What positive and negative lessons have you learned from your practical experience?

- What do you think of this document and any other documents from the OCR you have read?

From initial correspondence based on these and other questions, we hope to begin developing working relationships, collaborating together on specific projects, as it is through practice that unity is tested. It is too soon to start talking about international organizational forms, though we could imagine developing an international forum (i.e., something below the organizational level of the RIM) if there were a few communist organizations serious enough and with adequate unity to collaborate on creating one, which could lead to an international journal.

We welcome potential comrades from anywhere in the world based on ideological and political unity around firm revolutionary principles. Our international department will likely pay specific attention to developments and political forces in Latin America and the Caribbean given the potential of revolutionary struggle there to impact developments inside the US, including by way of immigrant populations in our country. We are also keen to find comrades in imperialist countries that are part of the imperialist bloc presided over by our bourgeoisie, as there could be great potential for joint activities.

Finally, while we believe that principled unity on questions of line is the most important aspect of international relations, we also think that having a good sense of humor is important, in case you hadn’t noticed from our writings. We take ourselves and our responsibilities seriously, but we use our wit against our enemies and joke around a lot with our comrades, and this is part of what sets us apart from dogmatists. So if you are interested in developing comradely relations with the Organization of Communist Revolutionaries, you’ll need to be able to take a joke.

Long live proletarian internationalism!

Down with long lists of dogmatic slogans at the end of communist documents!

1This organization has merged with others and is now called the Revolutionary Communist Party of Nepal.

2See, for example, the CPP’s December 2023 document “Rectify errors and strengthen the Party! Unite and lead the broad masses of the Filipino people in fighting the US-Marcos regime! Advance the people’s democratic revolution!”

3See, for example, “The Crying Need for a Communist Vanguard Party Today,” the conclusion to our summation of the communist movement in the US, published as kites #8 and available in the library section of goingagainstthetide.org.

4On the RIMist approach, see “On the Struggle to Unite the Genuine Communist Forces” in A World To Win #30 (2004), much of which is a polemic against the Communist Party of the Philippines’ approach to internationalism and international relations, without, unfortunately, naming them as the target of that polemic.