GATT pamphlet series, published April 2025

Click here to download a PDF for distribution.

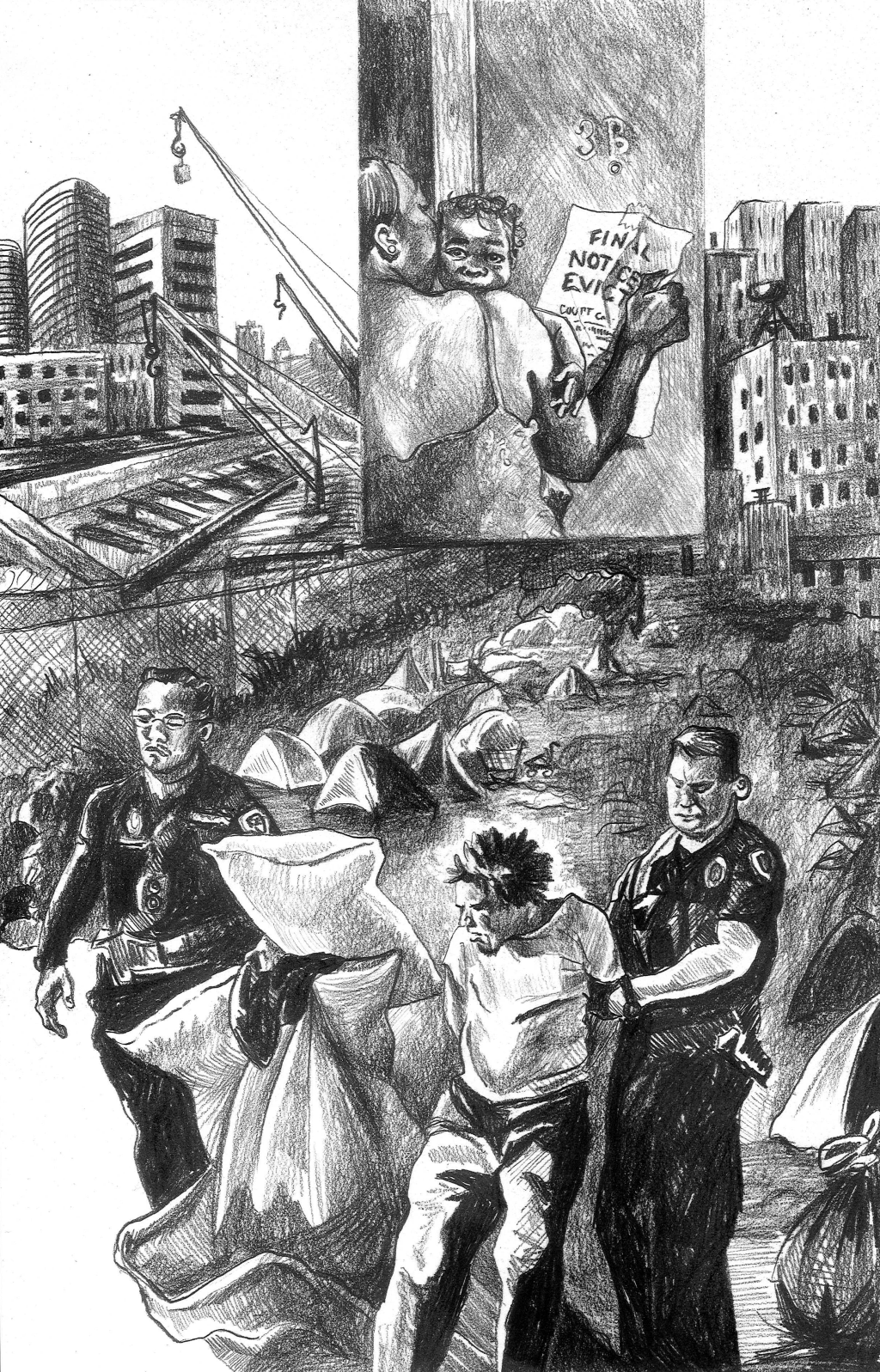

Look around any city in the US today, and you’ll see homeless people being pushed to the edges, camping out under highway overpasses only to be kicked out of their tents by the police. You’ll see luxury apartments being built and trendy, expensive shops open up while the people who have lived in the neighborhood for decades are pushed out by high rents, evictions, and the demolition of their buildings. The real-estate developers and politicians call what they’re doing to these neighborhoods “revitalization,” while the masses being pushed out call it gentrification. Why are those real-estate capitalists making so much money? Why are the politicians, even the ones who claim to be progressive, backing their moves? And why are more and more people left homeless or struggling to pay their rent?

Where did the jobs go?

Abandoned factories, covered with graffiti, can be found in cities all over the US. Prior to the 1970s, those factories were up and running and employed lots of people who lived in and around cities, and often with decent pay in the decades after World War II compared to jobs today. From the 1970s on, however, manufacturing companies moved their factories outside of the US to increase their profit margins in a process commonly known as deindustrialization. In truth, industrial production continued, but much of it was offshored and outsourced to the oppressed countries, especially in Asia, where workers could be more viciously exploited, with manufacturing companies spending less on wages, taxes, property, and safety regulations.

In the US, the loss of many factory and other industrial production jobs led to many people living in US cities becoming permanently unemployed, especially Black proletarians. For example, in the South Bronx, there were 2,000 manufacturers operating in 1959, but by 1974, there were only 1,350, with the number of manufacturing jobs dropping by a third. To the bourgeoisie—the capitalist class presiding over and profiting from production, trade, and finance—the millions of permanently unemployed became a surplus population, cast out of the legal economy, impoverished, and forced to make a living any way they could.

In the decades before the factories closed their doors, many white residents had moved out of cities for suburban homes in a process often called “white flight.” With steady jobs and access to bank loans, many white Americans flocked to the suburbs from the end of World War II in 1945 through the 1970s, while many Black people were corralled into urban ghettos, denied access to loans to purchase homes, and kept out of suburbs by racist discrimination. Consequently, city governments lost tax revenue due to white flight, leaving them unable to fix decaying infrastructure, fund education, and provide adequate public services. The combination of factories closing and cities left underfunded led to an ever more desperate struggle for survival. Proletarians stuck in urban ghettos had to work multiple low-wage jobs to survive or turn to the illegal economy, especially as crack-cocaine was flooded into their neighborhoods in the 1980s and the drug trade became one of the few growth industries offering employment to the youth.

As urban neighborhoods were left to rot and their residents left to fend for themselves, apartment buildings were neglected and abandoned and businesses closed down or moved out. Banks and financial institutions refused to provide the investment and loans that might have prevented this situation from spiraling downward, in a practice of racist discrimination called “redlining” Black and Latino neighborhoods. In the most neglected neighborhoods, such as in the Bronx and in Detroit, landlords would often pay someone to set fire to the apartment buildings they owned because getting the resulting insurance money for a burned out property was more profitable than collecting rent. For example, in the Bronx, as landlords set their buildings on fire to collect insurance money, the area lost 40% of its housing stock and 300,000 people moved away. Law enforcement largely looked the other way, and shuttered factories, burned out buildings, broken pavement, and abandoned lots took over the urban landscape.

Why did capital and the wealthy move back into cities?

Devaluation of urban neighborhoods laid the basis for a new round of development and profit-making from the 1990s to the present—not for the masses stuck living in urban decay, but for real-estate developers buying up devalued land and property and then renting to privileged sections of the population bored of suburban life. Many cities still had downtowns and central business districts, despite most neighborhoods around them being left to crumble by the government. Some urban districts became centers of immense wealth: lower Manhattan become the global center of finance capital, and Silicon Valley in California headquartered lucrative tech capital firms. With the wealthy who presided over finance and tech capital as well as many well-paid office workers they employed wanting to wine and dine in luxury, real-estate capital began to buy up property around central business districts. Then, beginning in the 1990s, many whose parents and grandparents had bought suburban homes in the preceding fifty years decided they would rather live in cities, where they could go to art galleries, take in live music, and enjoy artisanal shops and gourmet food. These people—members of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie, a privileged class that pretends to be progressive but lives a parasitic existence off the backs of the masses—became the frontlines of gentrification, from Brooklyn and the Lower East Side in New York to San Francisco’s Mission District.

Gentrification is driven by many different forces, including the influx of well-paid professional jobs, university campus expansion, the culture industry, transit-oriented-development, and generational preferences by the privileged classes of where to live. But the biggest beneficiaries of gentrification are the landlords and real-estate capitalists who make massive profits charging higher rents with little investment. Local politicians, local business owners, and sellout community leaders and nonprofit heads for the most part aid and abet these real-estate capitalists and landlords. Local politicians provide political support, usually a tax cut, and in return use this to bolster their political career and get a payout, either officially through campaign contributions or unofficially in other ways. Local business owners benefit initially by the influx of wealthier potential customers, and while some may last, others will no longer be able to afford the rent, and get replaced with high-end businesses who cater to the new clientele. Sellout community leaders and nonprofit heads can advance their careers, get more funding and corporate sponsorship for their organizations, and even launch into a political career by aligning with real-estate capital and working to prevent the masses from fighting against the hostile takeover of their neighborhoods.

The police play an essential role in facilitating gentrification by “cleaning up” the cities of “undesirables.” Before he was a pathetic sycophant for Donald Trump, Rudy Giuliani was the mayor of New York in the 1990s, where he pioneered the implementation of “broken windows” policing, using the rationale of “quality of life” to kick out and punish the homeless, the “squeegee men” (window cleaners), graffiti artists, and street vendors and lock many up in jail. Under Giuliani’s reign, the police used the policy of “stop and frisk” to harass Black and Latino youth and lock them up for petty crimes or for no reason at all. Brooklyn wouldn’t have been gentrified without the brutality of the police.

The federal government worked alongside local authorities during this same period, from the 1990s on, to defund and demolish public housing. Many of the projects, especially ones close to downtown business districts and in neighborhoods in the crosshairs of gentrification, were torn down, with their residents scattered or made homeless. Besides depriving millions of people of an affordable place to live, getting rid of the projects also destroyed longstanding family and community networks, leaving people to fend for themselves and unable to bind together to fight the forces displacing them.

How finance capital profited from and then crashed the housing market and left people without homes

While gentrification raised rents and displaced the masses from urban neighborhoods, the promise of home ownership came to a bitter end for millions in the late 2000s. Beginning in the 1990s, finance capital, concentrated in big banks, found creatively destructive ways to speculate on and profit from the housing market. Banks offered subprime mortgages to many people—proletarians, Black and Latino families—who previously could not get a loan to buy a home. These subprime mortgages featured low downpayments followed by predatory interest rates that the new homeowners would likely never be able to pay. Rather than call attention to the predatory practice, finance capitalists invented a financial product called mortgage-backed securities that lumped together subprime mortgages with more sound mortgages and sold them to investors. These mortgage-backed securities were consistently and falsely given good credit ratings, encouraging more investment and more speculation on the housing market, in turn encouraging the real estate industry to sell more homes bought with subprime mortgages.

Because homes were being bought up so quickly, home prices went up, and that created the illusion that prices would keep rising. As with all financial speculation on shaky foundations, eventually the bubble burst. When it finally became clear that many people couldn’t pay back their home loans and that lenders weren’t getting back their money, the entire economy went into crisis in 2007–9, with major banks and financial firms at risk of collapse without government bailout. After the housing market collapsed, after the subprime mortgage game was revealed to be a speculative scam, nearly nine million people lost their jobs and at least ten million people lost their homes after they were unable to pay off predatory mortgages and bank loans, with Black and Latino families hit especially hard. But the financial speculators, big banks and financial firms, and real-estate capitalists faced no real consequences, and the federal government poured hundreds of billions of dollars into the very banks and financial firms responsible for the crisis while doing nothing to help the millions who lost their homes.

How capitalists profited from housing again after the housing market collapse

Millions of foreclosed homes, now devalued and available at bargain prices, became the basis for a new round of profit-making for financial firms and corporations. Companies like Invitation Homes, created by Blackstone, the world’s largest private equity firm, led the charge in buying up these heavily discounted foreclosed houses starting in 2012, with more than 48,000 homes bought and $9.6 billion invested between 2012 and 2016. The ten largest single-family home rental companies own an estimated 196,598 homes. Initially, these companies were planning on holding the properties until the market improved to sell them to individual buyers, but they realized more profit can be made by renting them out. Furthermore, beginning in 2012, new technologies and algorithms allowed companies to instantly bid on thousands of homes at auctions across the country and run other analytics to maximize further profit.

What was once typically a “mom and pop” industry of single-family rental units has become a corporate, financialized affair. Investors can now make money off of real estate without directly owning property, often through publicly traded shares, via real estate investment trusts. The corporate takeover of the single-family home rental market led to greater rent increases and higher rates of eviction due to rents growing faster than wages. Furthermore, the new landlords—rental companies with vast sums of capital at their disposal and armies of lawyers on their payroll—pursue more aggressive eviction policies, confident in their ability to win in court against their impoverished tenants, who can’t afford rent, let alone a fancy lawyer. Because of millions of foreclosed homes in the wake of the 2007–9 crisis, corporations and investment firms were able to buy homes cheap and rent them out high, maximizing their profits, without regard for the people left out on the street as a result.

A temporary reprieve in 2020 followed by a rapacious assault on renters and the homeless

By the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, both single-family home and apartment rentals were increasingly in the hands of large corporate landlords, who related to their tenants as impersonal profiteers treating housing as a speculative investment. Many maintained secrecy of ownership and dodged accountability by using a so-called limited liability company. Corporate landlords have enforced stricter rental requirements, such as insisting renters pass a background check and have an income three times their rent, a high credit score, and no evictions in the last seven years. While these types of requirements have long been part of lease agreements, “mom and pop” landlords were often more lenient and could be negotiated with face to face. Corporate landlords, by contrast, often relate to renters entirely through an online portal and don’t allow for any exceptions to their rules. They never have to look their tenant in the eye or even know their name before throwing them out on the street.

In 2020, when businesses closed, many jobs and schools went online, and the government enacted social distancing measures to prevent the uncontrolled spread of COVID-19, there was a temporary reprieve on evictions. People left without jobs had greater access to unemployment benefits, stimulus checks boosted bank accounts, and temporary eviction moratoriums prevented landlords from kicking out tenants who could not pay rent. Moreover, many in the privileged classes escaped crowded urban neighborhoods for more secluded settings and many who couldn’t died from COVID-19, creating empty apartments and lowering rental rates. However, as soon as business returned to “normal,” corporate landlords set out on a mission to “recuperate losses,” raising rents and kicking out tenants who could not afford the “rebound” of the rental market. Rents jumped up by 30.4% nationwide between 2019 and 2023, while wages during that same period only rose by 20.2%. Eviction proceedings followed, with housing courts up and running to fulfill the bidding of corporate landlords.

Not surprisingly, homelessness has increased dramatically since the temporary reprieve on evictions and rising rents in 2020. There were 653,000 people who were homeless in January 2023, up 12% from January 2022, the largest increase on record, and up a staggering 48% from 2015. Rather than provide housing for those left out in the streets, government at all levels, including in “progressive” cities such as San Francisco and Los Angeles, has moved to further criminalize the homeless and carry out sweeps against homeless encampments, hoping to push those with no option but to sleep in a tent outside the city limits or locking them up in jail. In June 2024, the US Supreme Court ruled that it was not “cruel and unusual punishment” to arrest or give tickets to homeless people for essentially existing in public view, giving license and legal cover for the police and city governments to attack the homeless with a vengeance. In addition to law enforcement, vigilantes have joined in on brutalizing the homeless: in 2023, Daniel Penny, a former Marine, choked Jordan Neely, a homeless Black man going through a mental health crisis, to death on a New York subway. Penny only faced legal charges due to widespread outrage at his lynching of a Black man, but was acquitted in court and has since been invited to eat lunch with the president. Meanwhile, the police continue to shoot and kill homeless people and get away with it.

Who profits?

When it comes to housing today, at one end, we have real-estate developers, corporate landlords, and financial firms speculating on the housing market, the massive profits they make, and the police and government at all levels who protect their “investments.” On the other end, we have growing numbers of homeless people, renters struggling to get by and subjected to heartless rules and rising rents, and families unable to afford mortgage payments. This is housing under capitalism: private property increasingly in the hands of a small few, not the people who live in it. None of the schemes to build a few more units of “affordable housing” or a few more homeless shelters can solve the present-day housing crisis.

The problem is one of ownership: who owns housing, who gets to decide who lives where. Proletarian revolution—where the masses of exploited and oppressed people rise up and overthrow the capitalist class in power, destroy the government that protects them, and seize their property—can solve this problem in a day. Once you get rid of the corporate landlords and seize their property, all the housing they now own can be used to house those who need it rather than serve profit-making. Proletarian state power can guarantee everyone a decent place to live, without any threat of eviction. On the basis of overthrowing capitalism, resources and the creative power of human labor now trapped to serve profit-making can be put in the service of a social plan to rebuild and restructure the buildings and neighborhoods we live in to create a safe, fulfilling life for the masses of people. From each according to their ability, to each according to their need.

Selected sources

Meredith Abood, Securitizing suburbia: the financialization of single-family rental housing and the need to define “risk”, MA thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2017).

Khristopher Brooks, “Rents are rising faster than wages across the country, especially in these cities,” CBS News (May 8, 2024).

Clio Chang, “Who came up with those rental income requirements anyway?,” Curbed.com (December 12, 2024).

Alannah Dragonetti, “Flashback Friday: How the South Bronx went from devastation to destination,” GovPilot.com.

Alexander Ferrer, Beyond Wall Street landlords: how private equity in the rental market makes housing unaffordable, unstable, and unhealthy, Strategic Actions for a Just Economy (2021).

Alexander Ferrer, “Over two thirds of all Los Angeles rentals are now owned by speculative investment vehicles,” Knock-LA.com (March 10, 2021).

Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University, America’s Rental Housing 2024.

Neighborhood Assistance Corporation of America, “Blackstone profits from the foreclosure crisis,” InvitationTenants.com.

Colleen Shalby, “The financial crisis hit ten years ago. For some, it feels like yesterday,” Los Angeles Times (September 15, 2018).

Vivian Vázquez Irizarry, Gretchen Hidebran, and Julia Steele Allen, Decades of Fire, PBS documentary (2019).

Robert Worth, “Guess who saved the South Bronx?,” Washington Monthly (April 1, 1999).