By Kenny Lake

Our historical narrative left off [in part 2] with the US bourgeoisie making moves to resolve the mid-1970s conjunctural crisis for capital accumulation; however, some aspects of that crisis deepened for US imperialism through the late 1970s and into the early 1980s. The anticolonial movement continued to score victories, with the settler-built apartheid state of Rhodesia unable to defeat the armed national liberation struggle in its borders and under pressure from the British government to negotiate a settlement, resulting in the formation of Zimbabwe as an independent African nation in 1980 (and Bob Marley’s best concert to boot). Revolutionary warfare also gripped Central America, and while the US bourgeoisie actively propped up the most brutal counterrevolutionary forces there, they were reluctant to directly intervene with their own military given recent defeat in Vietnam and the risk of escalating conflict with the Soviet Union and handing a victory to them. As a result, the Sandinistas overthrew the US-backed Somoza dictatorship in Nicaragua in 1979. That same year, the Iranian Revolution swept the Shah from power and kicked US imperialism out of an important strategic location in the oil-producing Persian Gulf region.1

Politically, the world map of the late 1970s was in flux in ways helpful and harmful to US imperialism. The 1976 counterrevolution in China rid the international bourgeoisie of the greatest existential challenge it faced, namely large populations and territories on the socialist transition to communism, off limits to the logic of capital accumulation and posing a radical alternative to it. Under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, the new bourgeoisie in power in China made a strategic alliance with US imperialism, which served in the short term as a counterweight to Soviet imperialism and in the long term created new opportunities for capital accumulation by outsourcing industrial production to China. But some sort of “socialism”—not in the sense of the socialist transition to communism best exemplified by Maoist China, but in the sense of nationalized industries, social reforms, and popular mobilization—existed in a number of countries in the wake of victorious anti-imperialist struggles. Leaving aside whatever we consider Albania to be during the last years of Hoxha’s leadership,2 from Cuba to Angola to Vietnam, these “socialist” countries generally aligned with Soviet imperialism to some degree, tethering their independence to Soviet capital and relying on Soviet purchase of their exports, an imperialist relationship even if unequal exchange was less unequal with the Soviet Union than it would have been with the US. Consequently, Soviet imperialism became the greatest strategic challenge to US imperialism, with the former making substantial gains in Africa, Asia, and Latin America even as the latter still had the upper hand by far.

In the years after its 1975 defeat in Vietnam, US imperialism was on the ropes to some degree, getting hit with jabs and right hooks but, unfortunately, never a knockout blow. Rather than cowering in the face of challenges, the US bourgeoisie regained its footing step by step, finding methods and taking opportunities to overcome the 1970s crisis. Through that process, the US bourgeoisie consolidated its gains into a reconfigured system of global capital accumulation with US imperialism still on top, and triumphantly so in the 1990s. The boxing metaphor is fitting here considering the Rocky movies of the 1980s as symbolism for the Reagan administration’s drive to shore up US imperial might and project it around the world with a reactionary insistence on its God-given right to do so. The first decisive steps it took in that direction were in the realm of finance capital.

Well before Ronald Reagan took office, US government policy began freeing finance capital to move more freely around the world and exert itself over all other modes of capital accumulation. The Nixon administration’s 1971 decision to end the gold standard, wherein US currency was backed by gold, freed the monetary system from material constraints, at the same time as capital flows were freed from state controls. While this contributed to the bankrupting of New York City in 1975, it also enabled NYC to become the world’s center of finance capital, and rebuild itself as a global city—a nerve-center of global capital accumulation—on that basis.3 During the Carter administration, Paul Volcker took over as Chair of the Federal Reserve (the US’s central bank) in 1979 and began radically raising interest rates with the purported goal of curbing inflation, initiating the so-called “Volcker Shock” that led to a dramatic rise in unemployment in the early 1980s.

What was harmful for the masses proved beneficial for capital accumulation in the long term. The Volcker Shock started a set of economic policies enthusiastically pursued by the Reagan administration to consolidate finance capital’s dominance. Taxes were dramatically lowered for the wealthiest, and government regulations on finance capital were rolled back. The Glass-Steagall Act, an FDR-era response to the Great Depression, which separated commercial from investment banking, was rolled back (and ultimately eliminated by the Clinton administration), paving the way for the replacement of local and regional banks with a few large banking firms that sunk their tentacles into even the smallest of savings accounts to amalgamate bank holdings into vast sums of finance capital. When Volcker was unwilling to pursue these measures to free finance capital from government interference to the fullest, Reagan ditched him and brought on Alan Greenspan to chair the Federal Reserve in 1987, ensuring the institution served not as a check on the rapaciousness of finance capital but as its steward and support. For the masses in the US, this led to rising inequality. Around the world, it put US finance capital in position to pounce on new opportunities for the exploitation of labor and resources and the plunder of state assets, starting with the raised interest rates of the Volcker Shock resulting in a dramatic rise in debt payments owed by the governments of oppressed countries, debt payments they simply could not afford.4

How those new opportunities were manifested by the actions of US imperialism in a postcolonial world is a subject we shall turn to shortly. Before we go there, we must address two interrelated questions: How, after unburdening the bourgeoisie of paying taxes to a substantial degree, did the US government fund itself? And how did it strategically defeat the Soviet Union over the course of the 1980s, rolling back its gains and ultimately precipitating the collapse of its empire? Central to the answer of both questions is debt. In Reagan’s two terms, the federal government’s debt nearly tripled, and increasing military expenditure, in addition to lowering taxes on the bourgeoisie, was one of the main causes. While the threat of world war between the US and the Soviet Union loomed over the 1980s, what wound up transpiring was not nuclear holocaust but one side outspending the other. US imperialism bogged down the Soviet Union’s imperial ventures, in Afghanistan, for example, by supplying proxy fighters—including religious fundamentalists who would go on to become enemies of the US in its so-called “War on Terrorism”—with weapons. Moreover, the armaments spending spree under the Reagan administration forced its adversary to try to compete in the race for the most advanced weaponry—advanced weaponry that would likely have determined the victor in the event of world war—which effectively bankrupted state capitalism in the Soviet Union.

The US’s ability to win the military spending war rested on the alliances it had built up in the decades after World War II. Whereas the Soviet Union had junior partners in Eastern Europe and the support, and imperialist exploitation of, several newly independent oppressed countries, the US had fellow imperialist powers under its hegemony and a number of junior partners able to make important strategic contributions to its objectives. Oil-rentier bourgeoisies in the Persian Gulf region sent hundreds of billions of dollars of their petro-profits through US banks, which could then be invested as US finance capital saw fit.5 Trade and capital flows between the US and Western Europe, as well as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, constituted a mutually beneficial relationship and bolstered US military capabilities and government spending. And the Japanese bourgeoisie became an important purchaser of US debt, funding Reagan’s armaments spending spree with the profits of their manufacturing efficiency. In effect, US federal debt functioned as the lynchpin of a global gangster protection racket, wherein bourgeoisies in Japan, Western Europe, Saudi Arabia, and elsewhere agreed to fund US military spending, directly through purchasing US Treasury bonds or indirectly in other ways, in exchange for the US keeping the Soviet Union, and any other threats to their capital accumulation, in check.

In the Reagan 1980s, debt extended beyond military spending to permeate US society more generally. Corporate debt joined government debt as a mechanism for the US bourgeoisie to advance its strategic interests, economically in addition to politically. Consumer debt propped up the imperialist way of life that most Americans had come to expect, even as their wages declined and inflation drove up the price of their suburban homes and spending sprees at the shopping mall.6 But whereas for the US, mounting debt served to bolster its position as top imperialist power, in the oppressed countries it played a radically different role, re-subjugating them under foreign imperialism in new forms not long after they had cast off colonial rule.

Countering the crisis through (a return to) pillage: structural adjustment programs, plundering a social-imperialist empire, and privatization generalized

As explained in part two, all postcolonial governments faced the challenge of overcoming the effects of underdevelopment, and virtually all but Maoist China turned to loans from foreign banks and investment by foreign capital to develop their infrastructure and industry, hoping to pay for the imbalance through export production, which in turn ensnared them in the world market and disarticulated their economic base. By the late 1970s, virtually all oppressed countries had accrued crippling levels of debt to banks—private or government-run—in imperialist countries. With re-colonization not an option for the international bourgeoisie, the US reluctant to impose its will by massive military force in the wake of its defeat in Vietnam, and the US and its allies trying to outmaneuver Soviet imperialism, US-led imperialism weaponized debt to re-subjugate the oppressed countries. Conscious policy decisions were made to exacerbate the existing postcolonial debt and turn it into a means for dictating onerous terms of debt payment favorable for capital accumulation centered in the imperialist countries and catastrophic for the masses in the oppressed countries.

The Volcker Shock described above was one such policy decision. The US Federal Reserve raising interest rates meant that oppressed countries had to pay drastically more interest on their debt to US financial institutions. Volcker bringing interest rates up to 21% in 1981 set off a wave of defaults on foreign debt, beginning with Mexico in 1982. As interest rates kept rising, so too did the price of oil, as a result of conscious policy by US-aligned oil-rentier bourgeoisies in the Persian Gulf region as well as the disruption caused by the 1979 Iranian Revolution to international oil supplies. Oppressed countries had to go further into debt in order to purchase the oil necessary to fuel their economies, one of the prime reasons “total debt stock…quadrupled, from $400 billion in 1970 to more than $1.6 trillion” in 1982. Much of the oil profits were in turn funneled through US banks to become loans to oppressed countries to pay for more oil—a new triangle trade centered around debt rather than slaves.7

Suggesting consensus—or conspiracy—by the international bourgeoisie, the institutions created at Bretton Woods in 1944 to oversee the global monetary system and inject capital into rebuilding post-WWII Europe, namely the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), turned their attention to the oppressed countries and their mounting debt in the mid-1970s. Unlike in Europe, however, those institutions, together with the US government, were unforgiving of postcolonial debt, literally and metaphorically, and used it to impose their will. For example, in 1985, the US’s “Baker Plan (named after then Secretary of Treasury Richard Baker but drafted by his deputy secretary, Richard Darman) bluntly required the 15 largest Third World debtors to abandon state-led development strategies in return for new loan facilities and continued membership in the world economy.”8

By the 1980s, debt itself became an increasingly important lever of capital accumulation, with the financiers of debt (centered in the imperialist countries) collecting interest annually, making money because they had money in the first place, without having to undertake the pesky process of production to make profit. Consequently, finance capital strengthened its position vis-a-vis other modes of capital accumulation, especially on an international scale. But beyond capital accumulation through interest payments, the debt of the oppressed countries gave foreign finance capital leverage to dictate economic policy, buy off state assets at bargain prices, and pave the way for new rounds of exploitation. And so began a new wave of imperialist pillage in the 1980s called structural adjustment programs (SAPs).

Like global capital accumulation’s first wave of imperialist pillage led by colonial Spain, the SAP wave of pillage got its start by way of violent imposition in Latin America. A CIA-sponsored coup in Chile in 1973 overthrew the Allende social-democratic government and installed a military dictatorship under the leadership of Augusto Pinochet, whose second order of business, after a genocidal massacre of Allende’s supporters, was privatizing the state industries and assets that had been nationalized. From there, the Pinochet regime followed the economic policies advocated by Milton Friedman that demanded privatization wherever possible and the free flow of the free market to ensure optimal conditions for capital accumulation without government obstruction (but plenty of government involvement in setting the terms, as Pinochet’s coup exemplifies).

What was violently imposed in Chile became the model for all oppressed countries to adhere to, and in Latin America especially was often associated with military dictatorships.9 But debt was used to impose the dictatorship of international finance capital with or without a coup, giving imperialism a way to subjugate postcolonial governments through “peaceful” means, or at least by outsourcing military repression to those governments themselves. In exchange for some much needed debt restructuring and relief by the IMF and World Bank, oppressed countries were forced to agree to structural adjustment. They had to sell off state assets, deregulate their national market, slash social welfare spending and government subsidies for agriculture and national industry, and allow the free flow of foreign capital and trade into their borders, all so they could better afford to make debt payments. The beneficiary of this debacle for the masses in the oppressed countries was the imperialist bourgeoisie and finance capital in particular—they were the ones pillaging state assets, flooding markets with their products, and extracting resources and exploiting labor without the barrier of state protection. As anthropologist Jason Hickel points out, “By requiring debtor countries to privatise public assets, the World Bank and the IMF created opportunities for foreign companies to buy up telecoms, railroads, banks, hospitals, schools and every conceivable public utility at a handsome discount, and then either run them for private gain or strip them down and sell off the parts for a profit… The World Bank alone privatised more than $2 trillion of assets in developing countries between 1984 and 2012.”10

In addition, and perhaps more crippling in the long-term than the selling off of state assets, was the deindustrialization and reversal of state-supported agricultural production that took place in the wake of SAPs. In Africa and Latin America, gains made in industrial production were rolled back when SAPs stripped away state protections for national manufacturing and forced oppressed countries to open their markets to a flood of cheaply manufactured products from elsewhere, especially Asia. Consequently, the “big industrial metropolises of Latin America—Mexico City, São Paulo, Belo Horizonte, and Buenos Aires—suffered massive losses of manufacturing jobs.”11 Likewise, in

Abidjan, one of the few tropical African cities with an important manufacturing sector and modern urban services, submission to the SAP regime punctually led to deindustrialization, the collapse of construction, and a rapid deterioration in public transit and sanitation; as a result, urban poverty in Ivory Coast—the supposed “tiger” economy of West Africa—doubled in the year 1987–88.12

Often debt and SAPs started the process of deindustrialization and free trade agreements delivered the knockout blow. For example, in Guadalajara, Mexico, the robust small-scale factory and workshop economy collapsed in the 1980s due to the 1982 debt crisis followed by competition with cheap Asian manufactured goods that could more freely enter the national market after Mexico signed the Global Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in 1986.13

In addition to supporting industrialization, many postcolonial governments attempted to protect agricultural production with subsidies and tariffs and increase its output with state-supported mechanization, irrigation, and modernization. While those attempts only ever went so far outside of Maoist China due to the reluctance of postcolonial governments to challenge feudal relations of production and the landowner class, what little progress was made was reversed by the process set in motion by SAPs. Without state subsidies and facing competition from foreign imports, peasant producers were left to fend for themselves in the global free market, leading to land grabs and further reliance on cash crops rather than producing to feed the nation.14 Capitalist competition did not make good on its promises to lower prices for consumers; in India, for example, “deregulated food grain prices soared 58 percent between 1991 and 1994.”15 While higher food prices hurt the masses generally, the SAPs exerted the logic of global capital accumulation over the global peasantry far greater than even colonial rule had managed to do. For many peasants, that meant being driven off their land, no longer able to sustain themselves in agricultural production, and flocking to the growing slums surrounding cities in oppressed countries. For those still working the land, that land increasingly belonged to someone else, that someone else often meaning a foreign corporation, whether directly or through its intermediaries. Much of the global peasantry has changed in class character, exploited in a more capitalist than feudal relationship, whether by way of wages or market relations—a subject that requires more analytical attention from communists than I am capable of giving here.

By way of deindustrialization and the ruin of the peasantry, the SAPs opened the floodgates to the dramatic growth of slums in oppressed countries. As Mike Davis summed up,

The 1980s—when the IMF and the World Bank used the leverage of debt to restructure the economies of most of the Third World—are the years when slums became an implacable future not just for poor rural migrants, but also for millions of traditional urbanites displaced or immiserated by the violence of “adjustment.”16

The global slum population, which stands at over one billion today, points to an essential feature of post-SAP proletarianization: joining the ranks of the urban proletariat since the 1980s no longer goes hand in hand with factory employment in many cases. Instead, slum populations eke out a precarious existence largely dependent on informal employment, from street vending to rag picking to manufacturing without contract, as well as the illegal economy, with the growth of the drug trade a direct consequence of restructuring in the global capital accumulation process. Indeed, becoming a drug baron is probably the most rational bourgeois aspiration for the masses in the slums, even as it is only attainable for a small few, while working in the lower rungs of the drug economy has become one of the more viable forms of employment for many proletarians in oppressed and imperialist countries.

The growth of the global slum population in Africa, Asia, and Latin America points to the fact that the consequences of pillage by way of SAPs became a universal condition of the oppressed countries in the last two decades of the twentieth century, with few exceptions. In Africa, for example, there were 31 SAPs in the 1980s and 1990s, effectively reversing gains in independent economic development after the fall of colonial rule.17 The conditions of poverty imposed by the IMF and World Bank became the target of resistance by the masses of the oppressed countries, with 146 “IMF riots” from 1976 to 1992, often with women in the forefront.18 Harsh repression, by local governments rather than foreign military forces, put down these rebellions, and unfortunately, except in Peru, genuine communists were largely unable to play a vanguard role in diverting the seething anger at SAP pillage into revolutionary warfare. There was a reconfigured international proletariat and dispossessed peasantry facing profound levels of immiseration in the 1980s and 1990s with a common antagonism with imperialist finance capital, which did result in impressive resistance movements, but there was not an international communist movement capable of uniting that international proletariat to seize power anywhere.

Consequently, debt has remained an effective weapon to impose the dictatorship of finance capital on oppressed countries up until today, and while the main wave of SAPs took place in the 1980s and 1990s, structural adjustment remains a part of the imperialist toolkit as long as the promise of debt restructuring can be used to demand it. As Hickel notes, “since the debt crisis began in 1980, the South [i.e., the oppressed countries] has handed over a total of $4.2 trillion in interest payments to foreign creditors,” with debt service payments going from $238 billion per year in the 1980s to $440 billion in 2000 to $732 billion in 2013.19 Any government that refuses to fall in line with the debt regime has been overthrown (Sankara in Burkina Faso) or otherwise forced to submit to it (Syriza in Greece).20 Indeed, seemingly every victory in the anticolonial struggle gave way to capitulation to the dictates of foreign finance capital. As Horace Campbell sums up, if we look beyond Robert Mugabe’s bluster, we are forced to confront the fact that in independent Zimbabwe,

Socialist rhetoric and capitalist management of the economy between 1980 and 1990 gave way to complete capitulation to international and local financiers. The efforts of the first decade [of independence] to expand social services in the areas of health services, water supplies, public education and sanitation were confronted by the conditionalities of the economic structural adjustment programme.21

As the Zimbabwean experience suggests, since government debt is public debt, it is imposed on the masses as a whole. One postcolonial government leader far more principled than Mugabe, namely Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere, explained in 2000 that

Tanzania’s debt is about US$8 billion. Its population is 30 million. This meant that every Tanzanian man, woman and child carries a debt burden of about US$267. So far, if next year, Tanzanians decided to forego all of their earnings—in other words, if they decided to starve themselves to death in order to pay off their external debts—they would succeed in paying only about 78% of their debt burden. They would all go to their graves with an unpaid debt of US$57 per capita. That kind of poverty cannot pay off that kind of debt.22

That kind of debt in turn only led to more poverty, as “the number of Africans living in extreme poverty more than doubled” and “the number of people living on less than $5 per day increased by more than 1 billion during the 1980s and 1990s,” largely as a result of SAPs.23

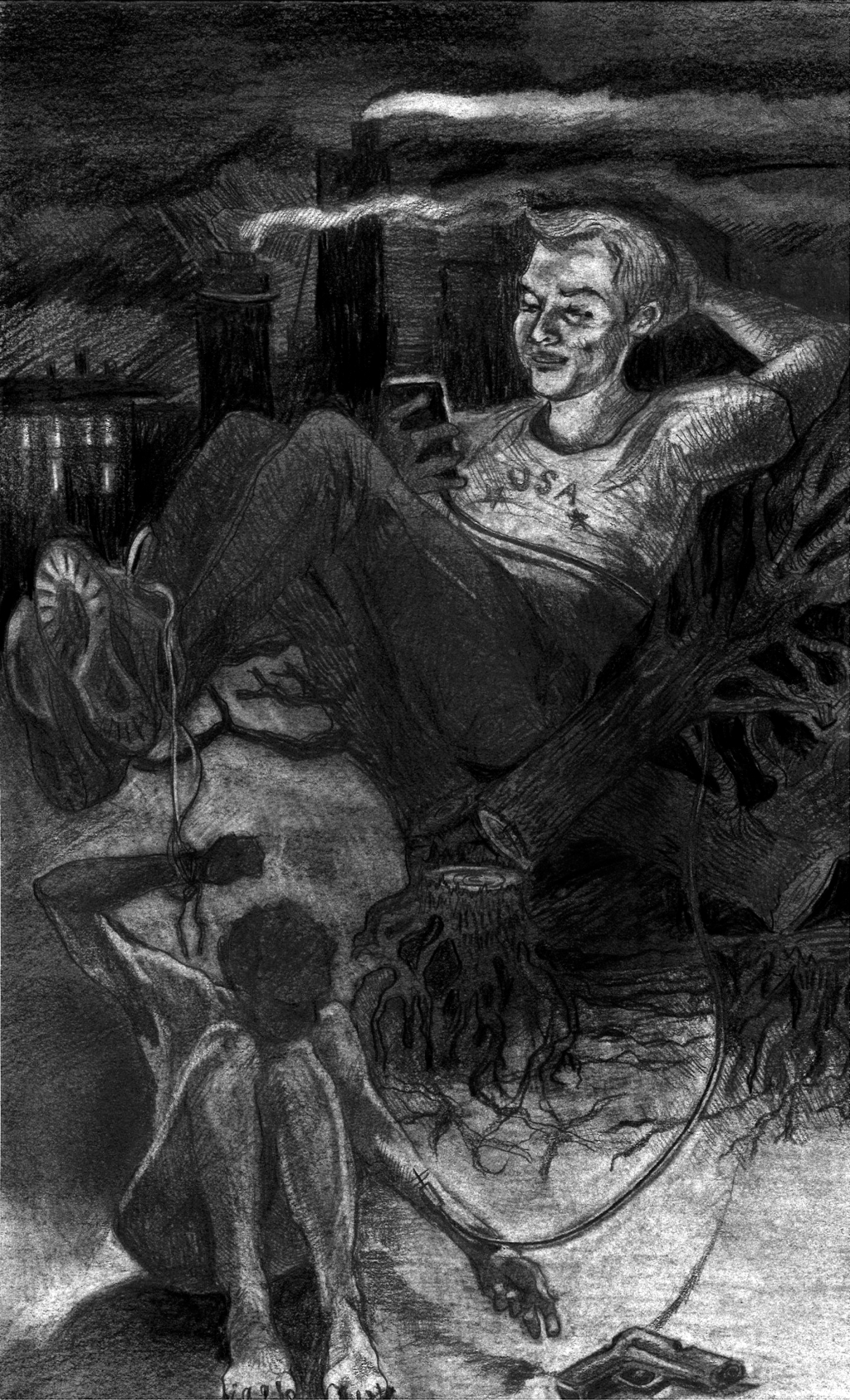

While leading to greater immiseration for the masses, the debt and SAP regime did sharpen class contradictions within oppressed countries. Unlike Nyerere, many postcolonial government leaders and the (aspiring) national bourgeoisies they represented sold out to the IMF and World Bank without much protest, at least not beyond words. Moreover, a nouveau-rich emerged in Latin America and Africa of “privatizers, foreign importers, narcotrafficantes, military brass, and political insiders” who took advantage of SAP pillage to advance their class positions on the backs of the masses. As Mike Davis pointed out, “Conspicuous consumption reached hallucinatory levels in Latin America and Africa during the 1980s as the nouveaux riches went on spending sprees in Miami and Paris while their shantytown compatriots starved.”24 The reconfigured and newly created bourgeois classes in the oppressed countries took on the character not of a national bourgeoisie in contradiction with foreign imperialism, but of junior partners and opportunist beneficiaries of finance capital centered in imperialist countries.

With the debt and SAP pillage playbook having proven so effective for imperialism in the oppressed countries, it was only logical that it be used on the former Soviet empire after the Soviet Union’s dissolution in 1991 due to losing its debt war with the US. The state ownership form of capitalism in the Soviet Union meant there was no shortage of state assets to sell off, and international finance capital as well as corrupt Russian government functionaries and the emerging Russian nouveau-rich bought them up at bargain prices. Vladimir Putin agreed to IMF dictates to end the generous government subsidies for housing and heat that the Soviet bourgeoisie had used to buy the allegiance of wide sections of the people, and as the cost of living skyrocketed, social services and infrastructure crumbled.25 While a small billionaire class rose to prominence in Russia, the privatization of state capitalism from which they gained their wealth provoked a wave of mass impoverishment, with the ranks of the poor in formerly “socialist” (in reality state capitalist after the mid-1950s) countries rising to 168 million from the 14 million it had been before the collapse of the Soviet Union.26 Whereas Eastern European socialist and then state capitalist countries had built up a robust industrial production apparatus, deindustrialization swept many Eastern European cities after 1991, with Sofia, Bulgaria and Elbasan, Albania becoming deindustrialized wastelands27 comparable to Detroit, Michigan.

In addition to fomenting an explosion in global poverty, SAP pillage and debt collection capital accumulation also led to material transformations in the exploitation and oppression of women and sparked reactionary revanchism against women and LGBT people on a global scale. In Africa and Latin America, “deindustrialization and the decimation of male formal-sector jobs, often followed by male emigration, compelled women to improvise new livelihoods as piece-workers, liquor sellers, street vendors, lottery ticket sellers, hairdressers, sewing operators, cleaners, washers, ragpickers, nannies, and prostitutes.”28 Women entered informal proletarian employment in large numbers, while still often bearing the burdens of the tasks of reproduction in the home. Furthermore, without state protections or formal contracts, women were preyed on and forced into some of the most brutal forms of exploitation, with the rise of prostitution and sex trafficking in Eastern Europe as one particularly horrific example.

Accompanying the material exploitation of women’s labor and bodies was an ideological exploitation of the fact that, as a result of SAPs, many men among the proletariat and peasantry had lost the forms of employment and status as breadwinner in the bourgeois family they previously held. That ideological exploitation took shape through the promotion of reactionary revanchism in different forms, with violent consequences. In the former Soviet Union, the rehabilitation of the Russian Orthodox Church, and its most reactionary patriarchal positions, went hand in hand with secular sexual violence against women and the re-assertion of male authority. In Latin America, femicide reached epidemic proportions, and was especially pronounced in places where women found employment in low-wage factory jobs while men struggled to find jobs comparable to their lost ways of making a living (see the 2009 film El traspatio for a chilling account of this reality). Ideologically, the wave of reactionary revanchism against women is evident in popular culture. For example, in bachata music, the soundtrack of the transition from campesinos to slum proletariat in the Dominican Republic, there was a pronounced shift in prominent lyrical subject matter from love (if often unrequited) to revanchism (against women) in the 1980s.

Elsewhere, LGBT people became the prime targets of reactionary revanchism. Uganda’s AIDS crisis is largely due to the fact that “Uganda spends twelve times as much per capita on debt relief each year as on healthcare.”29 However, the Ugandan ruling class chose to point the blame at gays rather than (its capitulation to) foreign finance capital, resulting in anti-gay violence and the passage of an Anti-Homosexuality Act in 2014. In Zimbabwe, the Mugabe government also chose to foment homophobia as a way to misdirect popular frustrations with the failed promises of liberation and with debt-induced impoverishment. Mugabe even attempted to give homophobia an anti-imperialist veneer, declaring in 1995: “Let the Americans keep their sodomy, bestiality, stupid and foolish ways to themselves, out of Zimbabwe”30 (if only he had kept American capital out of Zimbabwe). Assertions of patriarchy and anti-gay vitriol by the Zimbabwean government are another indication of how anticolonial struggles have been turned into their opposite in response to the re-imposition of imperialist domination by means of debt rather than colonialism. As Horace Campbell points out in Reclaiming Zimbabwe: The Exhaustion of the Patriarchal Model of Liberation, the frustrations of male soldiers who were part of the liberation war and the “the effort to claim [B]lack manhood” that was part of African anticolonial movements have been turned against women and LGBT people as an effective way to channel popular frustrations away from the new bourgeoisie in Zimbabwe and the imperialist bourgeoisie abroad.31 Whether reactionary revanchism emerges more organically from the masses or is engineered by the ruling classes, it gains ground in the absence of communist ideology and politics.

Just as the brutal techniques of colonial rule were brought back to the imperialist countries and used against sections of their populations, especially during World War II, the logic and consequences of SAP pillage that were mastered with devastating effects in the oppressed countries made their way to imperialist countries. Policies privatizing state functions and assets, eliminating state protections that benefited the masses, and using the specter of debt to slash social welfare spending were pioneered by the Reagan and Thatcher governments in the US and Britain, and have since become generalized operational procedures, extending further into imperialist society each decade. The results include erosion of many formerly stable forms of employment, decline in government services, increasingly dysfunctional infrastructure, and massive profit-making for the bourgeois beneficiaries of privatization generalized. While the stark divide between imperialist and oppressed countries remains, privatization generalized does connect the class antagonisms of the proletariat in imperialist and oppressed countries, even as those class antagonisms are far sharper in the latter. Moreover, it constitutes a thread across myriad methods of contemporary capital accumulation, from the breakup of the ejido communal land system in Mexico to the selling off of public housing estates in England, and the “[d]estruction of habitat here, privatization of services there, expulsions from the land somewhere else, biopiracy in yet another realm.”32

Often called neoliberalism,33 the sea change from Keynesian economic policies to the implementation of free market fundamentalism advocated by Milton Friedman was an ideological as well as a material victory for the bourgeoisie. It trumpeted entrepreneurship as salvation for the masses, delegitimized state provisions of social welfare and state economic planning, promoted the mysterious, God-like workings of the (capitalist) free market as a panacea capable of solving all social problems, and provided the bourgeoisie with a rationale for its insistence that “there is no alternative” to capitalism. Both the ideological and material side paved the way for how the logic of capital accumulation was reconfigured and consolidated around the world since the 1980s—not caught in an inexorable decline, as the “Marxist” political economists incapable of recognizing pillage as a means for the bourgeoisie to overcome crisis would have us believe.

US imperialism, and global capital accumulation more generally, resolved its 1970s conjunctural crisis not by restoring industrial production outputs and profitability in the imperial heartlands of North America, Western Europe, and Japan (an idea too idiotic for the bourgeoisie, who preserves its class power not by nostalgia but by innovation, to pursue practically but which many “Marxist” political economists obsess over intellectually). Instead, the international bourgeoisie turned to pillage—via SAPs, the dismantling of the Soviet empire, and privatization generalized—as a source of profit and as a means to exert class power over the oppressed countries, the losers of the Cold War, and the masses generally. That pillage, and the strength it gave to finance capital, did, however, create the conditions for a new wave of (industrial) production for the imperialist bourgeoisie to profit from, not in their home countries, but in the oppressed countries themselves.

Moving (from) production (to finance)

The fall of colonialism followed by the SAPs created favorable conditions for a new round of exploitation of labor in the oppressed countries in low-wage manufacturing. Among the onerous conditions postcolonial governments were forced to agree to under SAPs was allowing the flow of foreign capital into their countries, dismantling state support for national industry, and slashing protections, such as minimum wages and contracts, for the working class. In the 1980s and 1990s, multinational corporations and finance capital took advantage of those conditions and sped up the move, already underway, of many manufacturing lines from the imperialist to oppressed countries, where labor could be more profitably exploited and production streamlined to meet more flexible processes of capital accumulation. Often called deindustrialization, in truth this process kept core production functions, such as armaments manufacturing, the energy sector, and subsidized food production, in the imperialist countries, along with a smaller portion of entrenched industries.34

What production lines were moved to the oppressed countries was a selective process that kept the technological and productive advantage in the imperialist heartlands, while failing to develop the industrial base of the oppressed countries in ways that would serve their economic self-reliance. Essentially, the proletariat in the oppressed countries produced cheaply manufactured goods for export, not to sustain and develop their own countries. And the imperialist bourgeoisie set up manufacturing in the oppressed countries in the most flexible ways possible, enabling it to move production from one place to another based on where it would be most profitable, and to pull its capital out of obsolete lines with no regard for the consequences for the producers. The anarchy of capitalist production reigns in ways that benefit the imperialist bourgeoisie.

Technological advances in transportation (containerization, for example) and information and communications technology certainly made the new global assembly line more possible and more profitable,35 but the key bourgeois innovation was organizational. As Intan Suwandi sums up, contemporary capitalist production “is increasingly organized in global commodity chains, governed by multinational corporations straddling the planet, in which production is fragmented into numerous links, each representing the transfer of value.”36 The controlling center of production is in the imperialist countries, where the bourgeoisie retains “exclusive access to knowledge, technology, and development”37 and can keep much of their capital liquid. Production itself is largely outsourced to the subordinate manufacturing bourgeoisie, a class in the oppressed countries tied to and dependent on imperialism and finance capital but usually formally independent as subcontractors. As Suwandi describes the relationship, with

arm’s length production, even more than with traditional direct foreign investment, what is being produced are mere links in a global chain of value, in which particular nodes of production are digitally specified and controlled from abroad. The entire production system is designed to be highly mobile and can be rapidly shifted elsewhere if unit labor costs rise unduly.38

Politically and practically, this was one more nail in the coffin of colonialism as a form of imperialism, since the imperialist bourgeoisie could now go “all over the world in quest of gains instead of seeking an exclusive economic territory of its own.”39 Ideologically, arm’s length production gave the imperialist bourgeoisie the added benefit of “plausible deniability” of the source of its profits in the superexploitation of the proletariat of the oppressed countries. What is bought by consumers in the imperialist countries and displays the brand names of multinational corporations (think clothing labels) has been purchased by those corporations from suppliers (i.e., the subordinate manufacturing bourgeoisie) for cheap. The process involves “the exchange of more labor for less, in which monopoly-finance capital at the center of the system benefits from high markups on [the products of] low-cost labor” in the oppressed countries.40 The profitable unequal exchange has made the imperialist bourgeoisie come to prefer arms-length outsourcing over foreign direct investment within the internal hierarchy of multinational corporations, minimizing risk to themselves and hiding the labor exploitation that makes their profits.41 To accurately calculate the exploitation today, we would have to take into account “the increasing role of value capture and value extraction, as opposed to direct value generation, in determining the profits of multinational firms.”42

The vertically integrated firm with which the US bourgeoisie rose to its top imperialist position has been superseded by a new corporate model—think Walmart or Amazon rather than Ford or General Motors—that uses decentralization of production to amass a huge supply of cheap products to be sold at superprofits, products which in turn prop up the imperialist way of life with abundant consumption. As Giovanni Arrighi described it, whereas General Motors “was a vertically integrated industrial corporation” rooted in the US economy, “Wal-Mart, in contrast, is primarily a commercial intermediary between foreign (mostly Asian) subcontractors, who manufacture most of its products, and US consumers, who buy most of them.”43 But it is not just the structure of multinational corporations that has transformed under the new regime of global production, but also the global structure of class relations. We have already made clear the relationship between the imperialist bourgeoisie and their junior partners in production, the subordinate manufacturing bourgeoisie in the oppressed countries, who do not constitute a national bourgeoisie developing industry that serves the home market, but instead focuses on export production. Of greater consequence is the changed location of the industrial proletariat.

Whereas only 34% of the world’s industrial workers were in the oppressed countries in 1950, the downfall of colonialism tipped the balance toward the oppressed countries. 53% of the world’s industrial workers were in the oppressed countries by 1980, and after the SAP decades, that number reached 79%—541 million workers—in 2010.44 The new, low-wage industrial proletariat is drawn from the ruin of peasant production by the SAPs, and is disproportionately made up of women workers. The subordinate manufacturing bourgeoisie uses peasant dislocation and patriarchy to its advantage to more viciously exploit these workers, and the lack of traditional male breadwinner roles in the new industrial proletariat is another factor fueling the wave of post-SAP misogynist reactionary revanchism.45

The new industrial proletariat is a product of migration, from the countryside to export processing zones (EPZs)—specialized manufacturing regions in oppressed nations making goods for consumption in imperialist countries, which further the problem of uneven and disarticulated economic development. The workers in EPZs are more disposable than the post-WWII industrial workers of the imperialist countries, receiving little specialized training because they work in flexible, low-skill manufacturing, and because the imperialist bourgeoisie may decide to move production to another export processing zone anytime it wishes. The latter fact makes labor struggles for higher wages and better conditions difficult considering the bourgeoisie’s option to move production in the face of class struggle. A recent example of this phenomenon is the manufacturing company Foxconn’s relocation of iPhone production from China, where wages went up, to India beginning in 2019.46

The disposability of the new industrial proletariat makes it a double migratory class—the first migration (from countryside to EPZ) being the original act of proletarianization, the second being a move to a new export processing zone or a slum in the oppressed country or to an imperialist country in search of employment when EPZ jobs dry up. In combination with “the depeasantization of a large portion of the global periphery through the spread of agribusiness,”47 the new global organization of production has made the proletariat a more migratory class. In the imperialist countries, the immigrant proletariat provides the reproductive labor and services necessary for the functioning of the global cities (such as New York and London) where finance capital presides over the global production assembly line, their exploited labor keeping the system running that exploited their labor in their home countries and/or forced them to leave those countries.

Moving people (migration) and moving production (offshoring) both took shape through uneven development, not only between imperialist and oppressed countries, but also between regions, countries, and continents. Besides some regions becoming EPZs, outsourced production was concentrated in 24 oppressed countries, mostly ones with large populations from which to recruit industrial workers, while other oppressed countries were left out of the manufacturing part of the global assembly line. The result was a sort of reserve army of labor and surplus populations on a global scale that helped the bourgeoisie impose and maintain superexploitation of those working in production, especially when postcolonial governments such as in India eliminated protectionist policies, often as part of the terms of SAPs, and after socialism was overthrown in China, opening its large population up to exploitation by foreign capital.48

Much of sub-Saharan Africa was, in effect, “declared ‘redundant,’ superfluous to the changing economy of capital accumulation on a world scale,”49 other than as a provider of raw materials from mines and cash-crop peasant production. The ensuing rapid urbanization in Africa was not the growth of an industrial proletariat, but that of surplus populations cast off their land and traditional ways of life, forced to eke out an existence in slums. As Arrighi made clear, “the unplugging of these ‘redundant’ communities and locales from the world supply system has triggered innumerable, mostly violent feuds over ‘who is more superfluous than whom’”—essentially, fights over scarce resources, not “atavistic hatreds” or “power struggles among local ‘bullies’” as the imperialist ideological state apparatuses portray it.50

Asia, by contrast, became the world’s manufacturing belt for several reasons. For starters, US imperialism already had a strong presence there, including military bases and close political ties. US imperialism could rely on several junior partners, especially Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea, to help oversee the outsourcing of production. The Japanese bourgeoisie established a multilayered subcontracting system, which was expanded throughout Asia.51 South Korea moved up the ladder in manufacturing, ditching “such labour-intensive lines as footwear and apparel,” which were moved to Southeast Asia, in favor of “such technologically sophisticated products as cars, electronics, and semi-conductors.”52 Manufacturing firms headquartered in these junior-partner countries, such as Taiwan’s Foxconn, were often the ones directly overseeing production in other Asian countries, highlighting how arm’s length production works by outsourcing to industrial overseers. In Southeast Asia, the most exploited end of the manufacturing chain, US imperialism could count on the firm hand of bourgeois dictatorship in post-coup Indonesia and the Philippines to ensure the optimal conditions for labor exploitation. The result was a strong expansion of industrial production in Southeast Asia without much compensation—“no upward mobility in the value-added hierarchy of the capitalist world-economy.”53

What really made Asia the world’s manufacturing belt more than anything else, however, was the 1976 counterrevolutionary coup that overthrew socialism in China. Soon thereafter, Deng Xiaoping, the appointed political leader of the new Chinese bourgeoisie, made friends with US imperialism (and Ronald Reagan in particular) and opened up his country to foreign capital to set export manufacturing in motion. That foreign capital in turn benefited from the industrial base, infrastructure, and skilled workers with strong collective discipline created by a quarter-century of socialism. To those ready-made industrial workers were added large numbers of migrants from the countryside, as socialist collective farms and rural communes were broken up piece by piece.54 Though China never went through an SAP, the new bourgeoisie did seize and sell off state assets for their own enrichment, resulting in the collective labor of socialist construction being handed over to the grubby hands of privatization. State-owned industrial production was either made redundant or transferred to private ownership, resulting in mass layoffs of workers (36 million between 1996 and 2001) and intensified exploitation. China’s coastal cities, where industrial production was concentrated, went from “the most egalitarian in Asia” to among “the most egregiously unequal,” with a small portion of “nouveaux riches” existing side by side with a larger mass of “the new urban poor: on one hand, deindustrialized traditional workers, and on the other, unregistered labor migrants from the countryside.”55

As the Chinese experience indicates, local postcolonial bourgeoisies everywhere made “common cause with metropolitan capital to ‘open up’ the world for free flows of capital and of goods and services, to the detriment of vast sections of peasants and petty producers, and even small capitalists.”56 The loss of socialism, the sellout to imperialism of postcolonial governments, including ones that came to power through wars of liberation (Vietnam), and SAPs, where they were imposed, made large numbers of laborers available for outsourced exploitation serving foreign, mainly US, imperialism. Specialization created a division of labor and a hierarchy of exploitation across Asia, with Bangladesh becoming a center of the garment industry and India focusing on services (which, along with manufacturing, can be outsourced to oppressed countries depending on the type of service) and creating a large informal proletariat in its slums. The broader, global picture of capital accumulation that emerged is of Asia as the manufacturing belt, West Asia/the Middle East as the oil spigot, and sub-Saharan Africa providing raw materials and a growing reserve army of labor. Latin America and the Caribbean retained some manufacturing and agricultural production functions, but SAPs turned much of the populations there, migrating in large numbers from the countryside to slums, into an informal proletariat without access to regularized or traditional industrial proletarian occupations.

Both the surplus populations in Africa and the informal proletariat in Latin America point to a core contradiction in post-1970s capitalism-imperialism: the inability of capital to use the growing numbers of dispossessed peasants, ruined independent producers, and unemployed workers in the labor process,57 resulting in mass migrations, expanding slum populations, volatile conditions of life, the growth of the underground economy (including the drug trade and the sex trade), and every hustle for survival imaginable. To the extent capital tries to solve this contradiction economically, it does so by sending mobile capital into outsourced production while immobile capital employs immigrant labor (think, for example, of the meat packing industry in the US becoming run almost exclusively by immigrant labor).58 However, since this contradiction has only intensified since the 1980s, with ecological devastation adding fuel to the fire (sometimes literally) and growing sections of people more desperate for access to resources, the brute force of bourgeois dictatorship has stepped in to resolve the contradiction with repression. Controls on migration from the oppressed to imperialist countries, and the reactionary politics that go with them, are one stark example of this repressive political resolution.59

In imperialist countries themselves, moving manufacturing where labor could be more profitably exploited transformed the internal class structure beyond the aforementioned increase in immigrant proletarians. The post-WWII well-paid working class, working in or associated with industrial production, shrank in size but maintained its class position in key functions that could not be moved overseas for strategic or practical reasons, as well as in the leftovers of industries that flourished in the mid-twentieth century. In some instances, such as construction, there was a literal and visible split in the working class between an upper, well-paid, unionized, protected section enjoying the imperialist way of life and doing little actual labor and a lower, exploited, non-union section made up almost exclusively of immigrants doing arduous labor in dangerous conditions. Since the 1980s, many remaining well-paid working-class jobs have faced stagnant or declining wages, erosion of benefits and protections, and increased risk of being rendered redundant.60 New lines of manufacturing in imperialist countries have mainly been created where there are opportunities, for the bourgeoisie, to pay lower wages and to fight off unionization efforts, such as in US (mostly southern) states with “right to work” anti-union laws and in places with large numbers of immigrant proletarians.

Well-paid working class positions in manufacturing were replaced with proletarian jobs in the service industry. The US bourgeoisie fought for “an historically unprecedented repression of wage growth” in the 1980s and was thus “able to make profitable a large-scale transition into low productivity services that their rivals in Germany and Japan found difficult to duplicate.” The result was “a vast expansion of low-productivity, low-waged jobs, facilitated by the unmatched ‘flexibility’ of the increasingly union-free US labour market” in the service industry.61 The returns that the lower ranks of the bourgeoisie saw in the service industry, however, paled in comparison to the absurd profits made in finance.

As Robert Brenner sums up, “with low returns on capital stock discouraging long-term placement of funds in new plant and equipment, money went increasingly to finance and speculation, as well as to luxury consumption, the way being paved by an undisguised lurch in state policy in favour of the rich in general and financiers in particular.”62 Finance capital was in effect subsidized by US government economic policy and given every latitude imaginable, evading insider trading and anti-trust laws at every turn.63 Monopoly-finance capital’s pre-eminence was consolidated when the “Clinton administration pushed banking deregulation to its logical conclusion, abolishing the landmark Glass-Steagall Act of 1934 so as to open the way to the rise of huge conglomerates that combined commercial banking, investment banking, and insurance, typified by Citicorp and JP Morgan Chase.”64 The center of bourgeois power in the US and imperialist countries more generally became concentrated in banks and investment firms. There, members of the bourgeoisie often function as speculators more than anything else, keeping themselves detached from production, squeezing all they could from the assets they seized through mergers and takeovers, and moving with a vengeance to purge any economic activity that they could not make a desired rate of profit from—hence the wave of “corporate downsizing” of the 1980s and 1990s.65

Bankers, investors, and speculators were joined by insurance and real estate capital as the primary engines of capital accumulation and the most profitable sectors of the US economy, with real estate capital increasingly operating as a form of finance capital over and above construction and the housing market. A manufacturing big bourgeoisie independent of finance capital ceased to exist, for all intents and purposes, in the US and other imperialist countries.66 Besides financiers, multinational corporate heads presiding over outsourced global production and new tech capitalists (the “Silicon Valley” bourgeoisie), whose material products also depended on the global assembly line, occupy a place at the center of bourgeois class power in the imperialist countries. While still anchored to national markets in the imperial heartland, the big bourgeoisie became a more cosmopolitan class, financially meshed together in transnational corporate organization and investments and strutting the globe in their methods of capital accumulation.67

The post-1970s international bourgeoisie, which includes cosmopolitan capitalists, international bankers, investors, speculators, tech entrepreneurs, oil-rentiers, and the nouveau-rich in oppressed countries, share in common their culpability in a wide range of exploitation and dispossession of the broad masses. All their arguments about technological innovation and (capitalist) globalization portending progress for humanity have proven to be ludicrous lies, with virtually all measures of inequality increasing over the last several decades, between imperialist and oppressed countries and within both types of countries, and financial resources more concentrated in the hands of a small few than perhaps ever in human history.68 Just to cite one indicator, Intan Suwandi points out that, as of 2019, the 26 “wealthiest individuals in the world, most of whom are Americans, now own as much wealth as the bottom half of the world’s population, 3.8 billion people.”69

Whereas prior bourgeois fractions depended more on expansions of production and trade to ensure continual capital accumulation, today’s international bourgeoisie, with its distance from production and profit through finance, is not compelled to expand employment in ways that create a stable working class or enlarge the ranks of the petty-bourgeoisie.70 Besides the international bourgeoisie, the subalterns immediately below them are the only beneficiaries, enjoying luxurious lifestyles in a rarified, “high-cost, high technology market for higher-value, increasingly customized goods and services—whether designer clothing or luxury cars and homes.”71 If this is the “development” the international bourgeoisie prattles on about and praises itself for doing, it does nothing for the masses.

Widening, deepening, and broadening class antagonisms between the masses around the world and the international bourgeoisie, however, have not erased the distinction between imperialist and oppressed countries and the masses in them. The imperialist way of life may have eroded somewhat for broad swaths of the population of imperialist countries, but it is still propped up by the global assembly line, with the products of offshored manufacturing made cheaply available in the imperial heartlands, even if often paid for by consumer debt. Keeping those products flowing in a way that served imperialism depended on consolidating a new incarnation of free trade imperialism.

Free trade regime

Free trade has always been first and foremost the pursuit of imperialist powers whose prowess in production, fortitude in finance, triumph in trade and transport, military might, and global hegemony is unrivaled. In the nineteenth century, free trade imperialism reinforced the British bourgeoisie’s pre-eminent position in a global system of formal equality but actual inequality. As rival imperialists crept up on Britain’s lead by the late nineteenth century, free trade imperialism was negated by protected spheres of influence and colonial boundaries, which were subsequently fought over in two world wars. The negation of free trade was furthered by socialist states off limits to capital accumulation, postcolonial governments enacting protectionist measures for developmentalist purposes, and, from 1956 on, the rivalry between US and Soviet imperialism. During the decades of that rivalry, free trade prevailed among firm allies of the US via the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, but beyond that, separate spheres of influence defined who traded with whom.

Through SAPs, US imperialism began opening up trade in former colonies in Africa and Asia, battering down the barriers that had been erected after formal independence, while also working to whittle away at the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence. In addition, the US bourgeoisie pursued regional free trade agreements in the 1980s and early 1990s, such as the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation started in 1989 and the North American Free Trade Agreement implemented in 1994. These regional agreements allowed the US to flood the markets of oppressed countries (especially Mexico and in Southeast Asia) with its products and incorporated those countries more fully into the global manufacturing assembly line, ruining their peasantry and exploiting their proletariat simultaneously. After the main barrier to global free trade, the Soviet Union, collapsed and with postcolonial governments thoroughly subordinated by SAPs, the international bourgeoisie made a decisive negation of the negation, ending the separate spheres of influence of different imperialist powers that shaped world trade from colonialism through US-Soviet rivalry. They consolidated a global regime of free trade imperialism, presided over by the US bourgeoisie in a position no less powerful than the British bourgeoisie of the nineteenth century, with the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995.

As Jason Hickel sums up, whereas “structural adjustment imposed free-market policies on developing countries one by one, the WTO extended and standardised the neoliberal system across the global South in one fell swoop.”72 Under WTO rules, oppressed countries had to open their markets not only to products from the imperialist countries but also to capital flows, guaranteeing foreign capital the right to exploit labor around the world. The latter empowered the imperialist bourgeoisie to exercise control over the economies of the oppressed countries, who essentially gave up sovereignty over their national markets and the power to protect their agriculture, industry, environment, and labor from the dictates of free trade when they signed on to the WTO. While signing on to the WTO was ostensibly voluntary, centuries of imperialist-induced dependency, with the SAPs as the latest chapter in that saga, exerted tremendous pressure on oppressed countries to join or be cast out of the global supply line and face ruin (the other alternative being the kind of socialist self-reliance accomplished in Maoist China, which of course required proletarian state power).

Under the WTO, specific rules of international trade were constructed to benefit those who had the most property, in one form or another, in their hands. For example, the Agreement on Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) gave patent holders power over production and profit from technologies crucial to humanity. TRIPS is literally responsible for innumerable deaths from AIDS, especially in Africa, for it prevents anyone from manufacturing AIDS drugs without permission from the pharmaceutical companies, centered in imperialist countries, who own the drug patents as their property.73 In addition to WTO rules working to the benefit of those who hold the most property, imperialist participants in the WTO have come up with “work arounds” to those rules. For example, they have maintained subsidies for agricultural production within their home markets and then dumped their subsidized products on the markets of oppressed countries, where they can beat the prices of domestically produced goods and ruin the farmers who make them. Yet under the WTO, oppressed countries have been forced to end subsidies for their own agricultural production.74

In these and other ways, free trade imperialism under the WTO exemplifies how capitalism operates through processes of formal equality that mask real inequality. On the surface, the WTO creates a fair system of international trade between equal participants. But in reality, the participants are unequal based on their ownership of capital and control over products to sell, and real decision-making over the rules of trade gets done behind closed doors with no shortage of duplicity. The imperialist bourgeoisie claims that free trade will boost development in oppressed countries by allowing capital to flow into them and products to flow out. But the reality has been that each year, according to Hickel, the $2 trillion that flows into oppressed countries as aid, income, investment, and other forms does not come close to making up for the $5 trillion that flows out in the form of interest payments, profits to foreign investors, payments to patent owners, and various forms of unequal exchange. Making matters worse, oppressed countries are forced to compete with each other in the world market for investment and profits from exports, which only strengthens imperialist domination.75

One consequence of the WTO and the 1990s triumph of free trade imperialism under US hegemony more generally is that the logic of capital accumulation via the impersonal force of the market has become a stronger lever over the masses and even over the governments of many countries. While state power and military force remain absolutely necessary for imperialism (as we will explore below), the imperialist bourgeoisie is able to use all-out military intervention and occupation more sparingly when the laws of capitalist competition can compel countries to fall in line, in contrast to the direct and everyday reliance on colonial state power and military force in imperialism’s past.76

As a means to enforce those laws of capitalist competition, the WTO was an important final addition to the regime of global governance that the US bourgeoisie started constructing at the end World War II. From the 1980s on, US-led international institutions played more assertive roles in enforcing the imperialist order. As Giovanni Arrighi put it, “the IMF was empowered to act in the role of the Ministry of World Finance,” the UN Security Council took on “the role of Ministry of World Police” under the Bush Sr. administration, and “the regular meetings of the Group of Seven made this body look more and more like a committee for managing the common affairs of the world bourgeoisie.”77 The WTO became the means to spread global governance under US hegemony throughout an increasingly interconnected world economy, especially with many lines of manufacturing moved from imperialist countries to Asia and a more lateral flow of manufactured goods across the Pacific. As Arrighi put it, the “shift in the primary seat of the material expansion of capital from North America to East Asia constitutes an additional powerful stimulus for the US-sponsored tendency for the formation of suprastatal structures of world government.”78

With the strengthening and expansion of institutions of global governance under US hegemony came ideological rationales for their imposition around the world, sometimes called the Washington Consensus. Greg Grandin summed up this projected imperialist moral superiority complex as “a shared commitment to democracy, respect for human rights, market economics and free trade.”79 A crucial legitimizing mechanism for this ideological rationale was non-governmental organizations (NGOs), usually funded by imperialist bourgeois philanthropy and taking over social welfare functions in oppressed countries that had been cut under SAPs. Politically, NGOs acted as a bulwark against class struggle, dispensing charity and taking a condescending, clientelistic approach in response to mass impoverishment and buttressing imperialist notions of human rights, democracy, and empowerment through entrepreneurship. Whereas colonialism used missionaries to justify its brutalities and placate the suffering of its subjects, the free trade imperialism of the late twentieth century to the present relies on NGOs to put band-aids on slum poverty, proselytize the impoverished, and admonish itself of sin.

After the establishment of the WTO in 1995, the US bourgeoisie sought to expand free trade imperialism and integrate all countries possible into its system of global economic governance. It did so through new free trade agreements and expansions of existing ones, such as the 2005 Free Trade Area of the Americas, essentially an extension of NAFTA beyond Mexico and further into Latin America. But free trade imperialism met with resistance from the masses, such as the militant protests against capitalist globalization that haunted the meetings of imperialist economic institutions wherever they took place, even disrupting the 1999 WTO meeting in Seattle and fomenting splits among its participants. Furthermore, the US bourgeoisie expected it could add member countries to the WTO while maintaining its upper hand, but the addition of China in 2001 proved contradictory. On the one hand, it further opened China’s economy to US imperialism, but on the other hand, the Chinese bourgeoisie used the manufacturing prowess it had built up over decades to profit from WTO-enabled access to foreign markets, including the US.80

The US bourgeoisie’s 1990s dreams of some sort of Kautskyite ultra-imperialist heaven on earth, where the system worked smoothly to the benefit of the international bourgeoisie without competition among them causing conflict, was not to be. So it adapted, relying more on bilateral, multilateral, and regional free trade agreements (the proposed but doomed Trans-Pacific Partnership, for example) over the last couple decades while the WTO still plays a central regulatory role in global economic governance.81 And the US bourgeoisie has strengthened and relied increasingly on a crucial economic weapon of free trade imperialism in response to challengers to the rules of the game, namely sanctions.

When a country refuses the role US-led imperialism imposes on it in the global order, economic sanctions cut it off from trade flows and financial transactions, with the masses left to suffer the consequences as crucial necessities such as medicine and the means for maintaining infrastructure are prevented from entering the country and funds generated from exports dry up. British and French imperialism had tried sanctions after World War I to little success, and it was only under US hegemony that sanctions became an effective weapon in the imperialist arsenal. Post-revolution Cuba was the first primary target of US sanctions and has been their most longstanding victim. Iran was hit hard with sanctions after its 1979 revolution that overthrew the Shah, a loyal servant and junior-partner of British and US imperialism. Those sanctions prevented, and continue to prevent, the Iranian bourgeoisie from accruing the maximum profits possible from their country’s oil resources, in contrast to allies of US imperialism across the Persian Gulf, and Iran has also faced “a full financial blockade” in addition to restrictions on trade.82

Sanctions have become a sort of “instrument of first resort” for US imperialism, and their imposition on a few countries compels others to abide by the rules of free trade imperialism lest they be cast out like a leper and denied the ability to buy and sell on the world market. They also become a prelude to and rationale for US military intervention, which can be presented as necessary after sanctions did not prevent a defiant country from bowing down before the “rules-based international order.”83

Enforcement by the military supreme

While the US bourgeoisie has heralded the free market as an ideal mechanism that can diminish conflict by promoting peaceful economic competition according to established international rules, it has never been too high on its own fantasy to neglect the need for a pervasive military presence and occasional punitive military action to enforce those international rules. In fact, as Ellen Wood put it, “the more economic competition has overtaken military conflict in relations among major states, the more the US has striven to become the most overwhelmingly dominant military power the world has ever seen.”84 Decades before the 1990s triumph of free trade imperialism, the “United States emerged from the Second World War in possession of by far the most powerful conventional military forces ever assembled.”85 Superior naval power gave it the ability to enforce dominance over trade routes, while superior air force allowed it to stalk its adversaries from the skies, keeping tabs on their movements and threatening fast punishment on anyone who stepped out of line. Adding to the effectiveness of aerial surveillance was the Five Eyes program, an intelligence sharing operation between the primary powers of the Anglo-American Imperialist Alliance (the US, Canada, Britain, Australia, and New Zealand) but with the US exercising a privileged position within it, whose origins date back to World War II.86

The decolonization process made US military power and reach all the more important, as it denied imperialism direct administrative and repressive control over the oppressed countries, having to rely on local, formally independent bourgeois states for those purposes.87 Consequently, US imperialism worked to build a ubiquitous presence around the world, with an extensive network of military bases on the sovereign soil of other countries and consolidation and coordination under regional command structures, from Pacific Command set up in 1947, to CENTCOM overseeing the oil-rich Middle East region beginning in 1983, to AFRICOM’s creation in 2007. The result is an imperial military that is omnipresent and flexible, largely avoiding all-out war and occupation in favor of surgical strikes and ongoing deterrence. US imperialism’s military superiority relies more than anything else on the existence of that superiority itself—an ever-present reminder to its rivals and challengers of the potential punishment they could face.

Paying for that military superiority was a joint venture among the US’s fellow imperialist allies and junior-partners, with a division of labor among them wherein the US took on the role of protection. As we explored in part two, demilitarized Japan and Germany were allowed to outrun the US in industrial efficiency in the decades after WWII while outsourcing their protection to it so long as they paid their share of the costs. Western European countries accepted a US military presence in their borders in exchange for defending those borders from Soviet imperialism. Immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union, US allies were expected to foot the bill for any military interventions aimed at defending the “rules-based” international order of free trade imperialism. The first such post-Soviet intervention, the 1990–91 war on Iraq, was largely funded by US allies such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates with Japan and Germany also dutifully fulfilling their financial obligations. Those countries contributed $54.1 billion to the war effort, while the US only covered $7 billion. In this way, collective funding for US military actions was the financial confirmation of the “near-monopoly of the legitimate use of violence on a world scale” handed to the US by its allies.88 After that first US war on Iraq, the ongoing imperial logic of we shall protect you if you pay us to also served to build “uncontestable (and very expensive) supremacy” in the military sphere “clearly designed to discourage any substantial build-up of independent Japanese and European military forces—not because this ensures US predominance in the ‘realm of hard power’ but precisely because ‘hard power’ has its own effects on economic ‘leverage.’”89

The first US war on Iraq was also indicative of a shift in military strategy by US imperialism and its allies after US defeat in Vietnam. As Horace Campbell describes,

After the war in Vietnam, the military planners of the West refined the concept of air-land battle… The air force organised for the delivery of bombs, while the army mopped up after the bombing. This form of warfare was inordinately dependent on the air force. The strategy was linked to the fact that, from the 1970s to the turn of the century, the aerospace industry had become one of the prime military contractors for the military-industrial complex in capitalist countries. Advanced weaponry was deployed by the USA and NATO in the Gulf War, the wars in Serbia, and in Afghanistan.90

Between defeat in Vietnam and victory over Iraq, the US avoided any large-scale invasion by ground troops that carried with it the risk of large-scale defeat. Grenada in 1983 was an easy target, with the US military able to deploy overwhelming force against a small island nation that could not expect outside support in its defense. Whereas Grenada was relatively inconsequential to US imperial interests, Panama was small but strategically essential given the Panama Canal’s crucial role in world trade routes. When Panama’s military dictator, Manuel Noriega, went from firm US ally to non-compliant controller of his own personal fiefdom, Panama became the rehearsal site, in late 1989, of the US’s overwhelming power of aerial bombardment, to the detriment of the masses subjected to it. The invasion on the ground that followed it was a clean-up operation after the devastation from above, and posed little risks for US troops. After Panama, the US bourgeoisie had less need for military dictatorships in Latin America, with bourgeois-democracy resting on the threat of military force if that democracy was used to go against US imperial interests. Freed from the constraints of imperial rivalry with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the US could deal with non-compliant states like Noriega’s regime in Panama and Saddam Hussein’s in Iraq as it wished.91

The shift in the balance of imperial power indicated by US aerial bombardments of Panama and then Iraq also pointed to new strategic challenges facing US imperialism in a postcolonial, and then post-Soviet empire, world. As Ellen Wood pointed out, the local states that replaced colonial regimes “are subject to their own internal pressures and oppositional forces; and their own coercive powers can fall into the wrong hands, which may oppose the will of imperial capital.” Furthermore, postcolonial imperialism’s desire and necessity to keep many postcolonial governments in weakened positions with diminished state capacity has resulted in “disorder engendered by the absence of effective state power—such as today’s so-called ‘failed’ states—which endanger the stable and predictable environment that capital needs.” The collapse of central state power in Somalia is the paradigmatic example of imperialism’s “failed state” problem, and the US military’s attempts to resolve the problem in the mid-1990s failed miserably (with moments to celebrate if you consider “Blackhawk down” to be a joyous refrain). Even more of a problem for US imperialism than failed states is “the threat from states operating outside the normal scope of the US-dominated order,” such as North Korea and Iran.92