By Kenny Lake

Our historical narrative left off with the established European imperialist powers and the new Japanese one losing their grips on their colonies while the US took Britain’s place as the lead imperialist power. To understand the new imperialist order thereby created, we must first take a few steps back to examine the different path of development of US imperialism, from its roots in settler-colonies of Britain (addressed in part one) to the extension of US sovereign territory to industrialization to developing different ways of doing imperialism and monopolies, in contrast to the trajectories of empires built from old European feudal power turned capitalist.

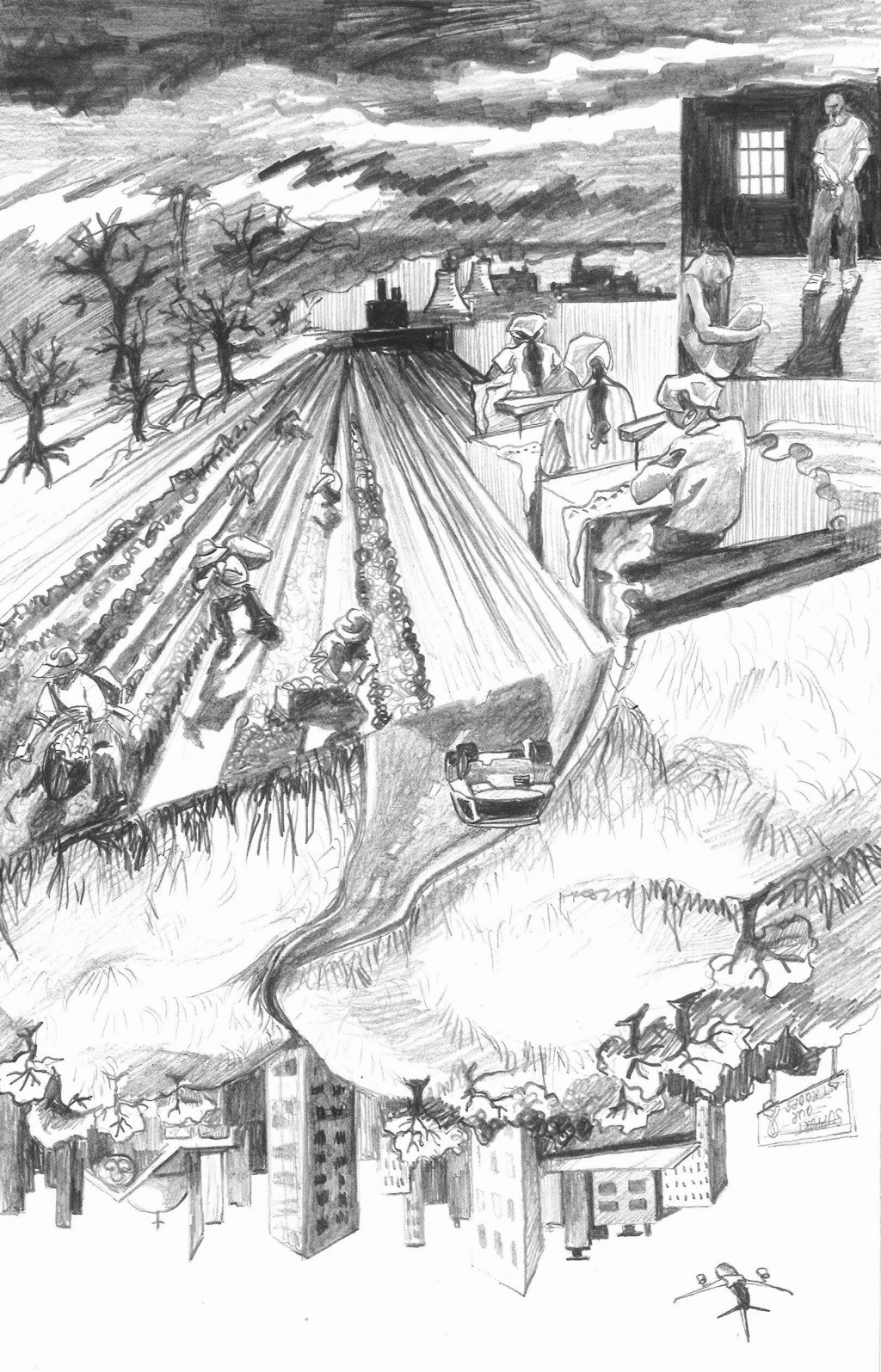

To vie for the position of hegemonic imperialist power, the US had to become a powerful nation-state in its own right with a solid economic base. Doing so involved a century of westward expansion after the original thirteen colonies gained independence from Britain, justified with the ideology of “Manifest Destiny” that viewed American territorial takeover as a God-given right. Westward expansion was a form of “internal imperialism” in which the US laid claim to territory in North America all the way to the Pacific, and even in the middle of the Pacific (Hawaii), genocidally expelling Indigenous inhabitants and fighting wars to seize territory where necessary (against Mexico in the 1840s to conquer what is today the southwestern US, for example).1 But within what became the continental US, rather than turning stolen land into administrative colonies ruled from Washington, DC, the land was populated by US citizens and recent migrants from Europe and incorporated into the US nation-state. That process spread the New England bourgeois ideal of the independent producer and property owner across the continent, with settlers setting themselves up as farmers and cattle ranchers on stolen land. Those independent farmers and ranchers created a solid agricultural production base that, along with protectionist policies, ensured a steady food supply for the home market, exports for abroad, and inputs for US industry.2

Contention over whether westward expansion would also involve the extension of the Southern slave plantation mode of production was one key factor that led to the 1861–65 US Civil War, the outcome of which firmly established the Northern industrial bourgeoisie in the dominant position over the Southern aristocracy. The latter had been content to subordinate themselves to world trade under British hegemony, while the Northern bourgeoisie had bigger aspirations, and enacted protectionist policies to strengthen its internal home market.3 The brutal exploitation of Black labor, as sharecroppers and proletarians instead of as slaves, continued to be a crucial means of capital accumulation, but principally benefiting the US rather than the British bourgeoisie.

As industrial production increased throughout the nineteenth century, especially after the Civil War, westward expansion became increasingly tied to industrial capital’s accumulation process. Gold rushes were joined by oil prospecting, and mines and other forms of resource extraction spread west, with capital coming in on the heels of the bottom-up initiative of a mass of people heading west looking to get rich quick by finding something valuable beneath the surface. Industrialization in turn changed the character of westward expansion, with railroads connecting the vast American landscape, cities springing up across the country, and factories emerging beyond the northeast. The peculiar form of US government that combined a strong federal government with decentralized power dispersed to individual states allowed for and encouraged regional economic diversity and specialization within a unified home market. As Giovanni Arrighi summed up, if “the continent-sized US ‘island’ was created through massive human and environmental destruction, it was the transport revolution and industrialization of war of the second half of the nineteenth century that turned it into a powerful agricultural-industrial-military complex with decisive competitive and strategic advantages vis-a-vis European states.”4

Geographically, those strategic advantages went beyond Britain’s. The US remained separated from conflicts in Europe not by a channel but by an entire ocean, while having excellent access to both Atlantic and Pacific Ocean trade routes, the latter becoming increasingly important in world trade.5 In addition to land fit for farming, between the Atlantic and Pacific was a diverse array of resources crucial for robust industrial production, including coal and oil, the older and newer fuels of industrial capitalism. With the consolidation of the US nation-state across the North American continent by the late-nineteenth century, the US bourgeoisie was positioned to expand its power beyond its shores and make a bid for imperialist hegemony.

(The precedent for) a different way of doing imperialism

While the “internal imperialism” that conquered and consolidated US sovereign territory was underway, the US bourgeoisie began to chart its own methods of external imperialism in Latin America. The opportunity for doing so was presented by the bourgeois-democratic revolutions of the early nineteenth century that broke Spanish and Portuguese colonial control over much of Latin America. In contrast to the territorial expansion of the US across North America, postcolonial Latin America was broken up into separate countries, each ruled by a landowning class whose class interests were best served by subordinating themselves to a world economy of free-trade imperialism. Those who did seek to develop a self-reliant economy with a home market under the command of an independent national bourgeoisie were repressed out of power, as in Paraguay. No substantial agrarian reform was carried out that would upend feudal class relations or create the basis for the development of independent capitalist powers in Latin America.6

While Iberian colonial overlords were kicked out of independent Latin American nation-states, the British bourgeoisie became their new imperialist master, but, as explained in part one, chose a free-trade form of imperialism that profited from unequal exchange in world trade and from debt and financial dominance. The US entered free-trade imperialism in Latin America as a junior partner of Britain, but laid claim to it as its sphere of influence with the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, ironically setting the terms for its own imperial politics by asserting freedom from European colonial rule in the Western hemisphere. Thereafter, US foreign policy shifted to assert greater imperial claims over Latin America. The Open Door policy of the 1890s insisted on access to markets in Latin America, just as industrial production in the US had created the need for the export of American manufactured goods to avoid a crisis of overproduction, while national industry in Latin America had been debilitated by British free-trade imperialism.7

Sharing in the policy of free-trade imperialism and unable to yet overtake British economic prowess in the nineteenth century, US imperialism could peacefully coexist with British imperialism in Latin America. But Spain’s continued colonial control over islands in the Caribbean and the Pacific became an increasing impediment to US imperialism, especially as the US started to overtake Spain in trade with some of its remaining colonial possessions, notably Cuba.8 This contradiction between economic power and territorial control was resolved by the 1898 Spanish-American War, in which Spain was defeated and the US took control over Spain’s remaining colonial possessions in the Caribbean and the Pacific, namely Cuba, the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico. The latter two remain US colonies to this day, while the former two were eventually granted independence under US domination—only the 1959 victory of the Cuban Revolution could kick US imperialism out of its stomping grounds.

Yet outright colonial control only served the US bourgeoisie in specific circumstances, and was likely applied in former Spanish colonies in part to break the local ruling classes’ allegiance to Spain, an allegiance based a long history of political and cultural ties, from Catholicism to the Spanish language. Instead of administrative colonialism, the US built a free-trade regime in Latin America based on the British precedent, propping up the most reactionary local rulers as needed, employing overt and covert military interventions, and putting US finance capital in command of Latin American economies. By the early twentieth century, this free-trade regime included control over the Panama Canal, a crucial seaway connecting world trade across the Atlantic and Pacific. Free trade was enforced by over a dozen US military interventions in Latin America in the early twentieth century, which were justified and provided a political rationale with the Roosevelt Corollary of 1904.9

Free-trade imperialism not only allowed for the sale of US manufactured goods in Latin America and the flow of petroleum, metals, minerals, and cash crops to the US through unequal exchange. It also gave US finance capital open access to Latin American markets. The 1913 Federal Reserve Act “allowed US banks to open branches in foreign countries,” and Latin America was their launching pad.10 Deposits in US banks operating in Latin America were then used to fund US corporations, effectively becoming a financial mechanism for US capital accumulation.11 US finance capital scaled up its operations, and by “the mid-1920s the apex of the US financial system consisted of three parts: banks close to US industry with branches in Latin America and Asia, the House of Morgan’s branches in Latin America, and links with the UK and French banks and self-financing US corporations exporting and investing abroad.”12

US finance capital increasingly became a lever of control over Latin American industry. US foreign direct investment (FDI) overtook Europe’s in Latin America over the course of the twentieth century. US investment tended to focus on extractive industries, such as petroleum and minerals, continuing the plunder and exploitation of Latin America’s natural resources that Spain had started while failing to develop industrial and agricultural production in a way that would serve the masses or expand national bourgeois power in Latin American nations.13 Even the so-called Good Neighbor Policy of the 1930s, enacted under the Roosevelt administration to deal with diminishing capital flows during the Great Depression, served to open the door wider to US investment—i.e., capital flow—into Latin America rather than being a break in imperialist policy, as it is often portrayed.14 A further enforcement of exploitation by way of foreign direct investment was the fact that Latin American governments became increasingly trapped by debt to US banks and financial institutions and, after World War II, to the US-led international finance regime of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. Interest payments siphoned money out of Latin American economies year after year, while debt relief was used to force further exploitation by US capital and, eventually, the sale and privatization of state assets on terms beneficial to foreign capital.

The late-nineteenth to early-twentieth centuries was a period of transition during which US imperialism worked with, and eventually supplanted, British imperialism and kicked out Spanish colonialism to secure its domination over Latin America. The profits from US exploitation of Latin America’s people and resources were pivotal to US capital accumulation, giving the US bourgeoisie the ability to contend for world hegemony. But beyond capital accumulation, the US bourgeoisie workshopped new, postcolonial forms of imperialist domination in Latin America before and after it gained the commanding position within global capitalism. After World War II, economically that meant imposing free trade and foreign debt on Latin America in ways that benefited US capital accumulation and continued US access to Latin American labor and resources. Politically, it meant finding ways to ensure that formally sovereign states complied with the needs of US capital accumulation. Those ways could include everything from influencing or manipulating elections to sponsoring coups and military dictatorships, such as the 1954 coup that ousted the Arbenz administration from Guatemala, to direct military interventions, Where the latter were employed, such as in the Dominican Republic in 1965, their aim was not lengthy foreign occupation, but to replace a government that refused to comply with the dictates of US capital accumulation with one that would. Along the way, the US built up deep ties with the military leadership of most Latin American countries, including through training them at the School of the Americas beginning in 1946, and relied on them as a reactionary bastion of enforcement. As always, free trade never meant a lack of state intervention, but went hand in hand with the most brutal forms of it.

The methods of postcolonial imperialism developed by the US in Latin America formed the basis for exerting US imperialist hegemony in a postcolonial world. In Latin America, the US bourgeoisie mastered the art of avoiding outright colonial administration or extended military occupation in favor of finding, and bolstering, local ruling classes and political and military leaders who could be relied on to serve US imperial interests. It set up a system of sovereign states while manipulating their political decisions from behind the scenes. It proclaimed freedom as its banner, in opposition to European colonialism and, later, the Soviet Union, while giving that freedom a decidedly bourgeois content centered on the “free market.” It advanced an economic and political system with US finance capital in command. And it constructed an international regime of preventive counterrevolution without colonial control to deal with the inevitable mass revolts, revolutionary wars for liberation, reformist governments, and nationalist challenges by national bourgeoisies to US imperialism. As European colonialism collapsed in Africa and Asia in the decades following World War II, the US bourgeoisie had the toolkit in hand from its experience in Latin America to make formal independence serve foreign domination.

A different way of doing business

Just like its European and Japanese counterparts in the late nineteenth century, the US’s position as an imperialist power depended, in its home base, on the merging of industrial and finance capital into large monopolies with vast command over resources, labor, and production processes. The second industrial revolution in the late nineteenth century, centered on the development of heavy industry and its need for larger concentrations of capital, gave rise to a new corporate capitalist class in the US at the head of those monopolies.15 But unlike in Germany, where monopolies formed through horizontal integration of different firms within the same industry, the bourgeoisie in the US oversaw the development of “vertically integrated enterprises.” These were created through the “integration of the processes of mass production with those of mass distribution within a single organization.”16 Since the German horizontally-integrated firm was the main paradigm that Hilferding, Lenin, and others used to analyze monopoly capitalism, it is important to understand the difference between it and the US vertically-integrated variety, especially as the latter was located in the imperialist power that came to a position of global hegemony after World War II.17

US firms certainly ate up competitors within their field to become monopolies, but the key capitalist innovation in the US was to put production and distribution, and all the sub-processes bound up with them, from the way components were put together into finished products to advertising those finished products, into one enterprise. Doing so meant that the “transaction costs, risks, and uncertainties involved in moving inputs/outputs through the sequence of these sub-processes were…internalized within single multi-unit enterprises and subjected to the economizing logic of administrative action and long-term corporate planning.”18 The administration and corporate planning in turn required a managerial regime in command of capital accumulation, headed by members of the bourgeoisie who took on the role of corporate executives and supported by their subaltern junior-partners in the corporate offices, with a whole corporate bourgeois culture created in the process. Those at the top of this corporate culture were then glorified in media and popular culture as the icons of entrepreneurial ingenuity and individual success rather than the exploiters of the American Psycho variety they are in reality.

The vertically-integrated monopoly not only changed the character of the bourgeoisie in command of it, but also affected the class structure of the US more generally. To realize a profit from its products, marketing became an increasingly important task for the corporate bourgeoisie to oversee. A growing consumer base was created within the US by sharing a portion of the spoils of imperialism with the US populace, and to placate that populace with the promise of prodigious products for its pleasure, marketing became the means to manipulate desire. A whole new lifestyle was created around the desire for endless consumption: the atomized existence of the American suburban family, whose life’s purpose was moving as far away as possible from proletarian and Black neighborhoods in order to enjoy home ownership, a car or two in the garage, manicured lawns, and a steady supply of the latest trinkets bought at shopping malls. In this respect, marketing by the vertically-integrated monopoly served not only capital accumulation, but also ideological indoctrination into a new form of possessive individualism, no longer predicated on settler seizure of territory but on suburban sprawl.19 That new form of possessive individualism bolstered white supremacy and patriarchy—the former by keeping Black people out of white suburbs and confined to ghettos, and the latter by keeping women confined to roles as suburban housewives.

Through this process, the US bourgeoisie created a home market of greater internal stability in the 1950s than perhaps any imperialist power had ever achieved. On the basis of its exploitation of the people and resources of the world and through the organizational structure of the corporation, the US bourgeoisie employed large numbers of Americans in relatively stable employment, in occupations ranging from petty-bourgeois to working class, who had the money to spend on the benefits acquired by imperialism and who developed an ideological disposition amenable to imperialist hegemony. In the US, the real proletariat—in the sense of a dispossessed class who work in conditions of exploitation or are cast off from employment as a reserve army of labor20—shrank as a proportion of the US population as a whole, while the proportion of people of oppressed nationalities in the US proletariat increased. Nevertheless, the US variety of imperialism did not eliminate the potential for revolution in the imperialist heartland, as the revolts of the 1960s demonstrated, but it did create a class structure more protected from proletarian insurgency.

From tea to Pepsi

In the early twentieth century, Lenin argued that in imperialist countries, the seal of parasitism is stamped on all of society, leading to a split in the working class between an upper, privileged section and a “lower and deeper” exploited section. After World War II, parasitism permeated deeper into imperialist society, the split in the working class in imperialist countries widened and solidified, and the petty-bourgeoisie grew and transformed with the needs of imperialism for professional workers in managerial, accounting, research and development, and other functions crucial to running an empire. With the US bourgeoisie in command, an imperialist way of life of relative stability, comfort, and consumerism spread throughout imperialist countries.

In the previously hegemonic British empire, tea makes a good metaphor for the nineteenth-century imperialist lifestyle. The tea leaves were picked by peasants in British colonies, namely India, and after brewing a pot, the spot of sugar added to a cup of tea came from Caribbean plantations while the milk was a product of the capitalist revolution in agriculture in England. Furthermore, the decorum and formality implied by afternoon tea betrays the leisurely lifestyle of those made rich by British empire, who held on to the cultural roots of British wealth in the landownership and lordship of the aristocracy.

With US empire, by contrast, Pepsi becomes a better metaphor for the imperialist way of life. It is the product of mastery of mass production and substitutes real sugar for high fructose corn syrup, an ingredient dependent on protectionist subsidies to US agriculture to ensure a strong home market, and comes in aluminum cans made from bauxite mined around the world. Moreover, the branding of a sugary syrup with fake fizz and artificial coloring shows how the mass marketing necessary to sell products created a whole new culture of crass consumerism, with the US bourgeoisie jettisoning pretenses to aristocratic decorum in the process. Along with the health problems and rotting teeth that come from imbibing a beverage laden with high fructose corn syrup and artificial ingredients, US imperialism also spread its vapid culture of crass consumerism as bourgeois aspiration around the world, even as the masses of exploited and oppressed were left with its maladies rather than opportunities for class mobility.

The imperialist way of life, and the bourgeois power at the center of it, was solidified after World War II through infrastructure investments and consumer product availability in the imperialist countries, forging a stable alliance of imperialist powers and junior partners under US hegemony, with a set of financial, political, and military institutions codifying that alliance, and ensuring that even as colonies became sovereign states, the flow of resources and the exploitation of labor still served capital accumulation in the imperialist countries. In what follows, we will take up each of these components, mostly in the order I have just presented them, keeping in mind that lurking in the background is the fact that as US imperialism secured hegemony, the international bourgeoisie contended with a vast socialist camp, whose territories and populations were off limits to exploitation.

The post-WWII decades in the US were a period, as David Harvey describes, of vast investments “in education, the interstate highway system, sprawling suburbanization, and the development of the south and west,” which “absorbed vast quantities of capital and product in the 1950s and 1960s.”21 Often referred to as Keynesian economics, investments in public infrastructure highlight the ongoing nexus between state finances and (industrial) capital, a nexus aimed at creating more favorable conditions for capital accumulation. It is easy to understand, when considering all the steel, concrete, and construction involved, how infrastructure investment benefited industrial capital. In this instance, the nexus of state finance and capital accumulation also created life conditions for the population of imperialist countries that separated them from people in the oppressed countries, with functioning roads, electric grids, sewage systems, schools, etc.

Another great nexus of state finance and industrial capital accumulation was the defense industry. US military spending only increased in the decades after WWII, and much of that spending went to purchase the latest armaments, largely produced by corporations and factories in the US. Outgoing US president Dwight Eisenhower warned of the dangers of a growing military-industrial complex in 1961, but in truth this nexus between state and capital was a crucial engine of economic growth, ensuring a steady demand for industrial products less beholden to market fluctuations than was the case in most other industries. Its other benefits included creating sections of the working class with stable, better-paying jobs and greater ideological allegiance to imperialism and a growing gap between US military prowess and the military capabilities of its rivals. The latter has always been crucial for imperialist hegemony, and was all the more necessary with the Soviet Union—a socialist country up until 1956—as a serious military power. Highlighting the dual role of weapons manufacturing in buttressing imperialist hegemony and facilitating capital accumulation, Giovanni Arrighi went so far as to say that rearmament during and after the Korean War “solved once and for all the liquidity problems of the post-war world-economy.”22 Indeed, the thriving US defense industry also did great export business, but selectively to countries functioning as allies or junior-partners of US imperialism (although here the anarchy of capitalist production has resulted in an increasing “militarization of the rest of the world”23 which does not always go as the US bourgeoisie intended).

While weapons manufacturing was a cornerstone of US industrial production, the post-WWII decades saw US manufacturing prowess more generally expand, with the bourgeois state playing a facilitating role in the process. Whereas in the nineteenth century, industrialization in Europe and the US created a growing mass of proletarians who threatened to become capitalism’s gravediggers, in the mid-twentieth century US, the bourgeoisie managed to negotiate a high degree of social peace with industrial workers. It did so fundamentally by sharing some of the spoils of imperialism with those workers and providing them with the previously described imperialist way of life, but also through a conscious policy of institutionalizing labor unions within the structures of bourgeois rule in the US and conceding higher wages and benefits for unionized workers. As Robert Brenner sums up, “If there was a major squeeze on profits by the action of labor at any point during the postwar epoch, it took place in manufacturing in the course of the 1950s.”24 That squeeze may have cut into profits, but it ultimately served US bourgeois class interests in shoring up a stable home base by bringing sections of the working class under bourgeois hegemony. Indeed, whereas the class struggles of the 1930s included militant strikes by industrial workers that threatened bourgeois power, class struggle by US industrial workers in the 1950s was more about negotiating a better distribution of the spoils of imperialism for themselves than contending for power.25

Workers in stable positions with higher wages, together with the growing ranks of the petty-bourgeoisie, could in turn enjoy the widespread availability of consumer products created by mass manufacturing. As Brenner describes, the “later 1950s and early 1960s had witnessed a major technological revolution—the initial introduction of new consumer durables such as televisions and electric refrigerators, new production durables such as silicon, steel plates, and polyethylene, and new methods of production such as thermal-electric power plants, strip mills, and transfer machines.”26 Those consumer durables, created using raw materials from around the world and manufactured with increasing industrial efficiency, filled suburban homes with the empty happiness of consumerist abundance.

The central role of the bourgeois state in stimulating and regulating demand for industrial products from WWII to the early 1970s has left many mystified, including some Marxists, as bourgeois economists have long insisted that under capitalism, government and private enterprise are realms separated from each other as are Heaven and Earth. In that confusion, the economic theories of John Maynard Keynes, who advocated greater government regulation of capital accumulation, especially via demand stimulus, are often treated as a specific period of greater state involvement in “the market.” As our historical narrative has shown, there is no time in capitalism’s history in which the bourgeois state was not actively involved in facilitating capital accumulation, only changes in how it did so. Keynesian economics made sense for the international bourgeoisie when securing class peace in imperialist countries was a top priority and to avoid a major crisis of overproduction and/or overaccumulation in the wake of the 1930s (on the latter, think of how much surplus capital was soaked up by the defense industry). Some supposed Marxists, such as Utsa Patnaik and Prabhat Patnaik, have suggested that the post-WWII period was one where the colonies as a market for industrial products were replaced with the state,27 but this downplays the reality that products from imperialist countries were still dumped on former colonies and the state has long been a primary purchaser of industrial products, especially armaments and infrastructure. In short, the divide between imperialist and oppressed nations still existed, as did the general flow of raw materials from the former to the latter and industrial products in the opposite direction.

Inter-imperialist collaboration under US hegemony

Greater stability in the US bourgeoisie’s home base went hand in hand with greater peace among imperialist powers after WWII, created by the decisive defeat of the efforts by Germany and Japan to carve out a larger piece of the imperialist pie for themselves. Weakened in Europe and losing its grip on its vast colonial holdings, the British bourgeoisie acquiesced to US hegemony in exchange for the benefits of second-place international exploiter. The US worked with Britain to smooth over the transition of its colonies to independent states still exploited by imperialism, and allowed the City of London to continue to play a central role in the global flow of finance capital, albeit second place to New York City.

Japan and West Germany, by contrast, were forced to accept US imperialist hegemony at gunpoint, with both occupied by the US military and not allowed to rearm themselves for years to come, and then only under US subordination. While the US bourgeoisie did radically restructure their politics and culture, with a de-Nazification campaign in Germany, they did not seek to thoroughly dig up the soil of fascism, even incorporating former fascist operatives into key positions serving US military and technological superiority.28 Nor did the US seek to subordinate West Germany and Japan as oppressed nations through pillage and exploitation. Instead, they respected them as fellow, if defeated, imperialist powers and rebuilt their economies as industrial powerhouses on par and in partnership with US imperialism.

The rebuilding of Japan and West Germany under US military occupation was a particular expression of a more general policy of US imperialism of shoring up political allies and trade partners with solid industrial bases in contention with the socialist camp led by the Soviet Union. The Marshall Plan from 1948 to 1951 pumped US funds into Western Europe to rebuild a shattered infrastructure and buttress industrial production. It ensured that Western European populations would be the beneficiaries of the postwar imperialist way of life, with well-functioning infrastructure, stable employment, and cheap consumer products—all necessary to covet bourgeois ideological allegiance and class peace when a compelling socialist alternative lay to the east.29

West Germany and Japan played a special role within this general policy of shoring up allies and equal trade partners exactly because they, unlike France for example, were under direct US military and political subordination.30 Consequently, the industrial production capacity of Japan and West Germany was allowed and encouraged to develop and even in some respects outstrip that of the US. Both countries had established strong industrial bases prior to their defeat in WWII, and had skilled labor forces and the remnants of a peasantry to draw into the industrial proletariat. Both were able to take technological innovations and production processes developed in the US and further perfect them, giving them the competitive advantage of a latecomer.31

The US’s arrangement with Japan and West Germany was not without contradiction, and eventually, in Radhika Desai’s words, “exacted a price: access to US markets and the further erosion of US manufacturing.”32 But as long as overall imperialist advantage remained in US hands, it could withstand and even benefit from trade deficits and disadvantages in industrial prowess while maintaining more crucial advantages in finance, political, and military power. Moreover, West German and Japanese industrial production provided much needed stability for the global capitalist system. In both countries, the contradiction between capital and labor was substantially blunted after the decade following WWII. In West Germany, labor unions were incorporated into the governance of industrial production, gaining a literal seat at the table, and union demands were curtailed to maintain profitability. The historic role of German Social-Democrats and union leaders as class collaborators with the bourgeoisie reached new heights in the 1950s and 60s. In Japan, seniority benefits, wage increases, and lifetime employment tied industrial workers to their employers and allowed the bourgeoisie to treat them as fixed capital and invest in their skills and education.33

The special role of West Germany and Japan as industrial powerhouses allowed to overtake US production capacity in some arenas and with privileged access to US markets was part of an overall condition of greater collaboration among imperialist powers in the decades after WWII. With the massive growth of the socialist camp and the wave of anticolonial revolt at the time, the imperialist powers all faced a great necessity to bind together in order to suppress or finesse the decolonization process and prevent or roll back the growth of the socialist camp. Furthermore, the socialist camp itself, and to a lesser extent some former colonies run by nationalist governments, were substantially off limits to trade with imperialist powers, making freer trade relations among imperialists and with oppressed countries under their subjugation a greater necessity. How to respond to those necessities was a matter of conscious policy in the economic, political, and military domains that was carried out and codified through a set of inter-imperialist institutions under US hegemony.

Institutions of inter-imperialist collaboration

If the role of the state under capitalism, broadly speaking, is to ensure optimal conditions for capital accumulation, then the role of international governance and military alliances under US imperialist hegemony is to ensure that capital accumulation functions optimally for the US bourgeoisie. To that end, at the end of WWII, the US led the formation of a new set of institutions serving its interests while inviting in the participation of other bourgeoisies, to greater and lesser extents depending on the circumstances. Of greatest extent but with the least power of execution was the United Nations, formed in 1945 as an international body of sovereign states. A core contradiction of bourgeois-democratic governance—between equality of participation and inequality of decision-making—is clear from the way the UN General Assembly serves as little more than a talk shop, while the Security Council makes all decisions of consequence, with the veto power of its permanent members frequently used by the US to preserve its interests. The UN does set some of the “rules of the game” as far as international politics goes, but its mechanisms of enforcement have been largely used against those who step out of line with the US-dominated imperialist order. In this respect, it has legitimized selected imperialist military interventions under the signboard of democracy, freedom, and universal human rights while doing nothing to prevent imperialist military interventions outside its banner. That line of legitimization started soon after WWII, with the US dubiously claiming that its war of aggression on Korea was carried out with the political authority of the UN. But with socialist states, former colonies turned nationalist states, and other state formations opposing US imperialism all having been or currently being participants in the UN, it has become a venue for bombastic statements but never a vehicle for truly challenging US hegemony. (Where is located after all?)

Far less toothless is NATO (the North Atlantic Treaty Organization), a military alliance of the North American and Western European powers formed in 1949 to coordinate containment of the Soviet Union and prepare for world war against it. William Pfaff has accurately described NATO as the “foreign legion of the Pentagon.”34 With the creation of NATO and where the UN takes decisive action, “the purpose of military power shifted decisively away from the relatively well defined goals of imperial expansion and interimperialist rivalry to the open-ended objective of policing the world in the interests of (US) capital,”35 which was only possible with the creation of the UN and its implication of a world governmental body.36 During the Soviet Union’s existence, these police actions were largely justified as containment measures, stopping the spread of “communism” (real or imagined). Conceptualizing military intervention as police action rather than war has continued after the collapse of the Soviet Union, finding new justifications in “failed states” and “terrorism” (real or imagined). The larger point is that in a postcolonial world, without the administrative and occupying role of the colonial state and military, US imperialism needed global military reach that was omnipresent but only making direct contact when necessary. For US imperialist allies and junior partners, “the United States offered effective protection at an unbeatable price,” funded by US surplus capital37—protection they needed, especially as the Soviet Union transformed into the center of a rival imperialist bloc with the restoration of capitalism in its borders in 1956.

Where the UN provided the international political institution and NATO the chief international military institution of US imperialist hegemony, the commanding heights of global finance were shored up in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire in 1944 before WWII had ended. There, representatives of the Allied powers met to stabilize global finance, well aware of how financial destabilization had contributed to plunging global capitalism into a grave crisis fifteen years earlier and of the need for financial stability to facilitate postwar reconstruction. The new financial system agreed to at Bretton Woods made the US dollar the world’s central currency, with other currencies convertible to it, and with the US dollar backed by gold—and thus guaranteed to be real money in the material, not just paper, sense—until 1971, when the Nixon administration ended the gold standard. Furthermore, at Bretton Woods, the two chief institutions of global finance—the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank—were created. The former ensured that reserve currencies would be available to countries in need of them to resolve payment issues, while the latter doled out loans with strings attached. At first, these institutions were primarily concerned with postwar reconstruction and focused their financial activities among the imperialist powers, but later they turned into financial enforcers over the oppressed countries.

The World Bank and the IMF were joined by the central banks of the imperialist countries, especially the US Federal Reserve, to govern global finance, with the US dollar as the principal denominator. Those central banks acted with greater foresight and a sense of responsibility for national bourgeois interests as a whole rather than just blocs of finance capital, in this way serving as a stabilizing mechanism.38 State intervention—on a national and international level—thus played a key role in preventing crises from spiraling out of control, like a responsible parent allowing room for its children to run wild on Wall Street but reigning them in if they get too out of hand. In the postwar decades, the “role of financial speculation remained relatively muted and territorially defined,” as David Harvey put it.39

The location and controlling interests of the IMF, the World Bank, and the US Federal Reserve Board of Governors in Washington, DC, the role of the US dollar as global currency of guarantee, and New York City becoming the global center of (private) finance capital meant that the “centralization of world financial power was even greater” under US hegemony than it had been under British or Dutch.40 The dollar market itself became a means to ensure US imperial advantage, as all countries engaged in the world market needed to keep a reserve of dollars, and as the dollar became the principal means of payment for crucial commodities such as oil. Western Europe itself became a conduit of US dollars, with US capital invested there, in dollars, and with dollars from the Eastern bloc directed through Western European banks.41

On the basis of the financial and monetary system set up at Bretton Woods, free trade agreements could be established with relative assurance of stability in currency exchange and payments.42 Chief among them was the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade established in 1947 and in effect and expanding until its replacement in 1995 with the World Trade Organization. More generally, “free trade” became the mantra of US imperialism, espoused with even greater religious fervor than it had been by the nineteenth-century British bourgeoisie. Practically speaking, it benefited the US and its principal allies, as they retained advantages in industrial production and, owing to their positions within the institutions of global finance, politics, and military enforcement, could continue to profit from unequal exchange even with the collapse of colonialism. But free trade fervor also served ideological purposes: it countered communism (real or imagined) with a bourgeois notion of universal freedom tied to entrepreneurial activity, and, like when the British bourgeoisie became abolitionist in the nineteenth century, it posed contemporary imperialist methods of capital accumulation as a progressive change over old ones, in this case administrative colonialism.

Trade, however, became second to foreign direct investment as a means of capital accumulation.43 More important to traversing national borders with goods to sell was for capital itself to cross borders, seeking out optimal investment opportunities in the postwar rebuilding process, in conditions of collaboration between imperialist powers, and, especially in later decades, in postcolonial sovereign states. The US “benefitted through its control of the largest, most dynamic, and best protected among the national economies into which the world market was being divided; and it benefitted through its superior ability to neutralize and turn to its own advantage the protectionism of other states by means of direct foreign investment.” While US corporations led the remolding of capital accumulation along these lines, the European bourgeoisie emulated their US counterparts and started “undertaking foreign direct investment at an increasingly massive scale.”44

As Giovanni Arrighi summed up, the “emergence of the free enterprise system—free, that is, from the constraints imposed on world-scale processes of capital accumulation by the territorial exclusiveness of states—has been the most distinctive outcome of US hegemony.”45 With that newfound freedom came the emergence of a key organizational innovation of capitalism under US hegemony, namely the twentieth-century transnational corporation, which brought together different blocs of capital, largely from imperialist countries, and crossed borders with ease in the processes of capital accumulation it set in motion. In contrast to the joint-stock company of capitalism’s past that engaged in military activity and state-building, Arrighi pointed out that “[t]wentieth-century transnational corporations…are strictly business organizations, which specialize functionally in specific lines of production and distribution, across multiple territories and jurisdictions, in cooperation and competition with other similar organizations.”46 Transnational corporations of a new type were able to thrive because of the sum-total conditions created by post-WWII US imperial hegemony: a stable system of international finance and currency exchange, prevailing collaboration among imperialist powers, and political and military enforcement of the global capitalist order under US command.

Junior partners: the subordinate manufacturing bourgeoisie and the oil-rentier bourgeoisie

While establishing collaboration among imperialists was at the core of shoring up US hegemony, building up a number of reliable junior partners served to buttress and extend that hegemony. Those junior partners performed indispensable functions in the global capital accumulation process and served as political-military forward operating bases against the hostile forces of national liberation, socialist states, and (after 1956) the rival imperialist bloc led by the Soviet Union. In return, they received US military and political protection, a greater degree of capitalist development than oppressed nations, and a higher “standard of living” for their populations to increase social stability. Most importantly, their bourgeoisies got to benefit more from global capital accumulation than the national bourgeoisies of oppressed nations.

An example of the dual function—economic and political/military—of the junior partners of US imperialism can be seen in the development of a capitalist archipelago in East and Southeast Asia. At the top of this archipelago was Japan, which the US allowed into the GATT and gave privileged trade and investment access in South Korea and Taiwan. Consequently, Japan “gained costlessly that economic hinterland it had fought so hard to obtain through territorial expansion in the first half of the twentieth century and had eventually lost in the catastrophe of the Second World War.”47 Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea were all allowed to develop, to greater and lesser degrees in the order I just listed them, into hubs of technologically advanced manufacturing. As Harvey describes it, their “economies specialized in taking innovations emanating from the US and using their labor resources and organizational skills to put the new systems into production at a far lower cost and at a far higher level of efficiency.”48

Three East Asian countries outdoing the US in certain lines of production was okay for US imperialism because, for starters, “much of the world’s research and development is done in the US,” which gives the US “sustained technological advantage.”49 More importantly, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan are all US military protectorates,50 with the former a forward base against China and the latter two hosting US military bases and large numbers of US military personnel. In this respect, these countries all set the paradigm for the dual role of US imperialism’s junior partners as advanced manufacturing hubs and military outposts. US imperialism imposed these roles on decolonized Southeast Asian countries to lesser extents—from US military bases in Thailand and the Philippines to the development of less technologically advanced manufacturing sectors with more exploited labor forces. The latter fact is indicative of the growth of a subordinate manufacturing bourgeoisie in the oppressed nations and in junior partner countries, which, as a class, manages and profits from key production tasks in global supply chains that are ultimately beholden to and benefit capital accumulation by the imperialist bourgeoisie in command of the larger process. A more unique junior-partner of imperialism is the city-state of Singapore, which was awarded a special role in the global flows of finance capital.

As an analytical term for the post-WWII world order, junior partner of (US) imperialism should be understood as a somewhat ambiguous position, or a spectrum, between imperialist and oppressed country that takes on aspects of both to greater and lesser degrees, or is in a process of transitioning from oppressed to imperialist country. While Japan is beyond a junior partner—it is an imperialist power in its own right—South Korea fits the junior partner paradigm perfectly, while other countries, like the Philippines, are clearly oppressed nations but with some junior partner functions. Being a fully-fledged junior partner of US imperialism generally involves being able to perform, or being developed to perform, a specialized task necessary for global processes of capital accumulation and/or political and military domination. One such specialized task that takes our narrative out of East and Southeast Asia is providing the principal fuel for industrial production and transportation of the last century, namely oil.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was consolidated in 1932 and at first had little strategic importance for imperialism. That quickly changed when, in 1938, petroleum was found beneath its surface beside the Persian Gulf. Not being a colony of a European power but lacking the industrial capacity and capital to develop oil production, the Saudi monarchy turned to the US bourgeoisie to cut a deal, and the US-dominated Aramco (Arabian American Oil Company) built up Saudi Arabia’s oil fields. As the landowners, the Saudi monarchy had considerable leverage to extract a more favorable deal with the US bourgeoisie to extract what lay beneath the surface, especially as Saudi Arabia became the world’s pre-eminent oil exporter. Hence the Saudi monarchy became an oil-rentier bourgeoisie and exercised greater control over oil production on its territory, profiting from where a crucial resource happened to be, and was allowed to do so by embracing its role as a crucial strategic junior partner of US imperialism. Some of the oil profits were shared with the Saudi population while “guest workers” from oppressed nations were brought in to be their servants, and the Saudi military was built up to play a policing role in the region.

In other Persian Gulf countries with oil beneath their surface, the old ruling classes followed the Saudi paradigm and became an oil-rentier bourgeoisie, or a rising national bourgeoisie either embraced the role of junior partner of US imperialism or tried to assert its class interests against US imperialism and suffered punishment by the imperialist order as a result. Indicative of the strategic importance of control over oil to US imperialism, there was a series of pro-US coups in and around the Arabian Peninsula in the 1950s. These coups served their purpose: by 1967, the US bourgeoisie controlled nearly 60% of Middle Eastern oil reserves—up from 10% at the beginning of WWII—while Britain, losing its colonies in the region in that time period, went from 72% to 30% control over oil fields, indicating the change of guard in the imperialist order.51 US military intervention to secure the flow of oil, and profits from it, in the right direction has only continued since then, with the “humanitarian” US president Jimmy Carter in the late 1970s cohering a political doctrine that the “US would use military force to defend its interests in the Persian Gulf region”52 and with subsequent wars against Iraq under presidents Bush senior and junior carrying out the Carter doctrine. While oil-rentier bourgeoisies have greater leverage than other national bourgeoisies owing to the resource they control, the message from US imperialism is clear: if you try to take that leverage too far, we will find someone to replace you.

The growth of the oil-rentier bourgeoisie provides us with important lessons about capital accumulation in general and about its motions over the last century. First off, oil profits depend on production (extracting oil from the ground), but it is landowners who often receive the greatest share. While certainly more efficient methods of getting oil out of the ground increase profitability, oil-rentier bourgeoisies risk lowering their profits if they pump out too much oil and saturate markets. They are a class with a vested interest in maintaining the status quo rather than dynamically transforming it. They do, however, accumulate capital in vast quantities, and the imperialist bourgeoisie is fine with allowing them a large share of oil profits so long as they remain its junior partners. The capital accumulated by oil-rentier bourgeoisies is partially used to fund lavish lifestyles, turning it into wealth instead of keeping it active in the production process, but large portions of it are also invested in production activities other than oil. Since countries where the oil-rentier bourgeoisie is the dominant class generally have low populations, little opportunities for agricultural development, and no strong basis or need for much industrial production outside of oil, much of their surplus capital is invested overseas, joining with the US-led trend of foreign direct investment. The operation of post-WWII global finance found a way for the US bourgeoisie to benefit from the motions of oil-rentier surplus capital by virtue of the fact that the oil trade is “denominated in dollars,”53 flowing through the conduits of US-dominated finance capital in Europe and elsewhere and strengthening US imperialism in the process even if the profits do not principally go to the US bourgeoisie.

Saudi Arabia and South Korea offer us examples of two types of junior partners of US imperialism—the former ruled by an oil-rentier bourgeoisie and the latter witnessing a subordinate manufacturing bourgeoisie outgrowing itself—both serving as key US political and military allies, albeit not without contradiction along the way. In both countries, as the rising capitalist classes consolidated their positions and accumulated surplus capital, they could expand their operations and investments and cast off residual stunted national bourgeoisie status. If maintaining imperialist domination is a game of chess, the junior partners of US imperialism are knights, rooks, and bishops, able to make unique moves, play a lane, and even stretch out across the board, but not able to go anywhere like the queen and beholden to their duty to protect the king (the US bourgeoisie) if they want to survive.

Making formal independence serve foreign domination

Turning a few former colonies and independent countries into its junior partners was one of US imperialism’s strategic solutions to maintaining dominance in a postcolonial world. But capital accumulation still depended on a divide between a handful of imperialist countries and a larger mass of oppressed countries, even if most of the latter were shedding their colonial status and becoming independent states. So the bigger strategic challenge for US imperialism from 1945–75 was to make decolonization as a whole, not just in a few places, serve its interests—how to finesse the transition from a colonial to a postcolonial world with the imperialist bourgeoisie still on top.

Several factors worked against a smooth transition to a postcolonial world dominated by the US bourgeoisie, and US imperialism developed a diversity of tactics in response. First and foremost was the growing wave of anticolonial revolt that reached its height in the 1960s and drew in a variety of classes and political forces. Where the US bourgeoisie or other bourgeoisies aligned with it (especially the French and Portuguese) tried to suppress that anticolonial revolt with military force, including by propping up a puppet regime that put local faces on what was in effect administrative colonialism, as in Vietnam, they failed.54 From Algeria to Guinea-Bissau to Mozambique to Angola to Vietnam, the imperialists were knocked on their asses by the masses, and their brutality only exposed the grotesque lengths they would go to defend their class interests. Moreover, the defeats suffered by imperialists reverberated back in their countries, sparking and radicalizing the 1960s revolutionary movements in the US, Europe, and Japan, undoing the social peace the imperialist bourgeoisies had cultivated in their home territories, giving rise to rebellion within the US military, and even leading to the fall of Portugal’s longstanding fascist government. The US’s 1975 defeat in Vietnam made clear that maintaining old-style colonial rule was too costly for imperialism in most cases, and a new form of imperialist dominance was necessary.55

Faring better for imperialism than counterinsurgency was finding pliant local partners who could steward independence without rupturing ties with their former colonial masters, and/or make new but no less subservient ties to US imperialism. Senghor’s government in Senegal, with its cordial relationship with French imperialism, is a good example of this scenario, and Senghor’s assertions of African cultural identity were acceptable to imperialism exactly because they did not affect Senegal’s economic or strategic relationship with the French bourgeoisie. The availability of pliant local partners depended on the internal class and political dynamics of each anticolonial struggle and how those dynamics interacted with the external factors of socialist states and, after 1956, a rival imperialist power. For analytical purposes, we can focus our attention on Africa, where almost the entire continent was subject to European control during the period of high colonialism.

The class interests of virtually everyone in Africa were impeded by colonial rule, but in different ways and to different degrees. As Walter Rodney pointed out, the largest class, the cash-crop peasantry, a creation of imperialism, was in conflict with the general workings of capital accumulation, forced to sell what they produced on a world market mediated by the general anarchy of capitalist production and in the specific conditions of colonialism. The imperialist bourgeoisie reaped the greatest share of the profits from African cash crops, while middlemen traders and usurers in Africa functioned as junior-partner exploiters of the cash-crop peasantry. Smaller in number than the cash-crop peasantry were miners, plantation workers, and urban proletarians in various occupations who were directly exploited as wage-workers by the imperialist bourgeoisie and their local agents. The smallest class was the educated elite, who worked in low-level positions of the colonial administration (clerical workers, educators, administrators, missionaries, etc.) but whose upward mobility was strictly limited by colonial rule. The educated elite became the intellectual and political leadership of the anticolonial struggle in Africa.56 The question was how much it was willing to unleash and lead the masses of people and in what direction.

The answer to that question is where stand (with the masses) and political line (what direction to take the struggle of the masses) become intertwined. Amilcar Cabral, for example, developed his stand into a political program of people’s war to expel Portuguese colonialism by force and fuse the revolutionary leadership with the masses in the process. For this he was assassinated shortly before independence was won, and unfortunately we will never know what kind of postcolonial policies he would have led. Other anticolonial leaders in Africa, such as Sékou Touré, Kwame Nkrumah, Julius Nyerere, and Patrice Lumumba, worked to combine a mass movement with electoral victories to wrench independence from the European imperialist powers who recognized they could no longer hold onto their colonies by force.57 The independent governments they led sought to implement radical social reforms with mass participation, aimed at transforming formal independence into full economic, political, and cultural independence.

In the case of Lumumba, the Belgian and US imperialists opted for assassination to ensure that mining and rubber in the Congo kept benefiting capital accumulation by the imperialist powers, with Mobutu installed as a loyal servant and allowed to enrich himself for his service to imperialism. In Nkrumah’s Ghana, a combination of sabotage and espionage, with CIA involvement, led to a coup in 1966 that ousted Nkrumah less than ten years after Ghana’s independence. The fate of Lumumba and Nkrumah indicate the importance of the international espionage wing of the US bourgeoisie’s global regime of preventive counterrevolution, especially but not only the CIA (Central Intelligence Agency). Not just in Africa but also in Asia and Latin America, the US bourgeoisie perfected the art of assassination, manipulating elections, and mobilizing local military personnel to carry out coups against governments using formal independence in ways that conflicted with the imperatives of US capital accumulation, whether that was nationalizing resources and industries, developing self-reliance, or aligning with a rival power. From Iran to Brazil to Indonesia to Guatemala, espionage efforts allowed the US to avoid direct military intervention while installing governments willing to do its bidding.58 The development and deployment of covert tactics rather than open warfare and the urgency with which the US bourgeoisie moved to depose postcolonial governments stepping outside of US dominance was conditioned by the threat of those governments joining the socialist camp and, after 1956, by imperial rivalry with the Soviet Union for oppressed countries to exploit.

Perhaps more important than regime change, however, was constructing a global regime of subordination to imperialism that could bring to heel even those independent governments that survived the subversion efforts of spooks. To that end, US imperialism took advantage of several contradictions in the anticolonial struggle and its aftermath, all of which can be seen keeping our focus mostly on Africa. One of those contradictions was between the class interests of the leadership of that struggle with the broader masses who constituted its social base. The idea of a national bourgeoisie held back by imperialism in the colonies has always been a murky notion in Marxist analysis, as the structures of administrative colonialism prevented much development of a national bourgeoisie in the first place, instead creating petty-bourgeois elements playing the role of middlemen traders between the imperialist bourgeoisie and the masses in the colonies. That did not prevent the educated elite leading the anticolonial struggle from developing bourgeois aspirations, but realizing those aspirations proved difficult after independence was won because they had little access to capital.

Lack of capital was joined by the fact that, especially in Africa, colonialism had carried out little development of infrastructure—the railways and roads, power grids, and built environment necessary for (industrial) capital accumulation. As Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò sums up, under colonialism, “African lands were considered only good for extraction, and whatever infrastructure was put in place was not designed to improve the welfare of the colonised or the future development of their lands. They were colonies earmarked for supplying raw materials for the industrial enterprises of the metropole and, simultaneously, held as captive markets for the finished goods manufactured there.”59 The easiest and fastest way to gain capital for industrial production and secure funding for infrastructure development was to turn to foreign bourgeoisies. While various mechanisms for independent economic development were tried by postcolonial governments, from tariffs to import-substitution industrialization, ultimately most of them sought out collaboration with foreign capital. Infrastructure projects were funded by foreign banks and financial institutions, including the IMF and World Bank, and joint ventures invited the participation of foreign companies for their capital and for their monopoly on the technology needed for industrial production.60 Even Nkrumah’s government relied on foreign capital and finance for development projects, funding efforts to generate hydroelectric power from the Volta River with loans and capital from the World Bank and the US company Kaiser Aluminum, who could in turn set terms for how the power was used, and Ghana became indebted to foreign finance.

In addition to industrialization and infrastructure was the agrarian question. Colonial populations were majority peasant, and demands for land, an end to feudal and plantation exploitation and usury, and better prices for cash crops were all part of the anticolonial struggle. These demands were more often than not betrayed by the leadership of newly independent governments, who may have been willing to unleash the peasantry in the course of the anticolonial struggle but whose bourgeois aspirations made them fear the full implications of peasant demands and the ongoing participation of peasants in the postcolonial political process. As Utsa Patnaik and Prabhat Patnaik argue, drawing on Lenin,

Where the bourgeoisie come late to the historical scene, it is afraid that any attack on landed property may rebound into an attack on bourgeois property, and thus makes common cause with the landed interests in defending private property, even though this entails arresting the democratic revolution in the country. Therefore, the dirigiste regimes that came up in countries where the bourgeoisie, or proto-bourgeois elements, had played a leading role in the anti-colonial struggle invariably eschewed any radical land redistribution.61

Furthermore, while postcolonial governments carried out development projects to increase agricultural production, these were ultimately defined by “intense competition among them for pushing out more and more primary product exports to obtain the foreign exchange required for industrialization”62 Postcolonial bourgeoisies joined the longstanding bourgeois tradition of industrialization on the backs of the peasantry, but with a postcolonial twist—they sold agricultural products on the world market and then used that money to buy industrial means of production from imperialist bourgeoisies. Consequently, even agricultural policies aimed at industrial development ensnared postcolonial bourgeoisies to foreign capital and to a world market defined and dominated by imperialist powers while screwing over the peasantry in their own countries. With the failure of most postcolonial economic policies to improve the conditions of the peasantry and with an end to strict colonial controls on who could live in cities, rural to urban migration massively increased but without a corresponding uptick in urban formal employment and infrastructure—the basis for the rise in slums and the informal proletariat, a subject we shall return to in part three.63

In both industrial and agricultural production, most postcolonial governments failed to rupture from the world market, at best fighting for better terms (higher prices for their products) but more often competing with each other over who could sell exports the cheapest. Orienting production towards export also had the effect of keeping former colonies specializing in the cash crops and production lines they had been relegated to during colonialism. As a result, they were on the receiving end of the worst effects of the anarchy of capitalist production, facing ruin when the export they specialized in confronted a drop in demand or price on the world market—a world market in which the imperialist bourgeoisie had the dominant position.

Highlighting the way that production for export by oppressed countries can only impede their economic independence is what happened to Cuban sugar plantations—the production specialization imposed by imperialism on Cuba for centuries—after the Cuban Revolution. While the Cuban revolutionary government defiantly severed ties to US imperialism, it found a new sugardaddy in the Soviet Union. Rather than implementing land to the tiller and reorganizing agriculture, including what crops were grown, to serve the needs of the Cuban people, the Cuban government kept the sugar plantations intact and sold sugar to the Soviet Union instead of the US. The Soviet Union gave Cuba a better price for its sugar than Uncle Sam had, but the trade relationship that developed kept Cuba dependent on the Soviet Union for capital, technology, and means of production for the functioning of its economy.64 When relying on export production to facilitate development, the best an oppressed country can do is use rivalry between imperialist powers to cut a better deal with one of them.

Post-revolution Cuba’s relationship to the Soviet Union brings into focus a question that has been coming increasingly into the forefront of our narrative, namely how the socialist camp and the transformation of the Soviet Union into a capitalist-imperialist power affected the anticolonial struggle and its outcome. The large socialist camp that emerged at the end of World War II provided ideological inspiration, political and material support, and practical training to anticolonial movements and illuminated a potential path of human liberation to take after independence was achieved. The Chinese Revolution in particular showed the strength of communist leadership in the anticolonial struggle in fully mobilizing the masses, especially the peasantry, and thoroughly destroying the forms of state power used to enforce imperialist domination. Furthermore, socialist China from 1949–76 under Mao Zedong’s leadership demonstrated both the necessity and possibility of self-reliance in developing agricultural and industrial production serving the needs of the masses and fully under their control, especially after the end of Soviet aid to China in the late 1950s. The socialist camp and Maoist China in particular not only took territory and people out of the logic of capital accumulation, but presented a strategic challenge to that logic the world over. Every move the US bourgeoisie made to establish and maintain its global hegemony in the decades after WWII was made with that strategic challenge in mind.

Unfortunately, the Maoist path of self-reliant socialist development was not pursued outside of China. To the extent Maoism shaped the anticolonial struggle, it tended to be as a set of strategies and tactics for mobilizing the masses to overthrow colonial rule, but not as a total(izing) ideology and politics where the principle of relying on the masses applied to the socialist transition period as well. That explains why, in Vietnam, Zimbabwe, and elsewhere, the mass line method of leadership, the doctrine of protracted people’s war, and the concept of new-democratic revolution were applied to varying degrees during the anticolonial struggle, but the postcolonial governments in those places failed to carry out any thorough socialist transformation of society relying on the masses and instead kept their countries in the web of imperialist exploitation.

In opposition to the Maoist model, what was pursued by postcolonial governments not under US domination mostly fits into two general categories: falling under Soviet imperialist dominance or attempting an independent path of developmentalism riding the rift of imperialist rivalry between the US and the Soviet Union. The former took shape based either on Soviet political and material support for the anticolonial struggle (for example, in Angola) or turning to the Soviet Union for capital and technical expertise after independence (as in Cuba). Driven by the logic of capital accumulation but with the state as the main actor, Soviet social-imperialism—socialist in name, imperialist in content—became increasingly pro-active in seeking to shape the outcome of anticolonial struggles to its benefit, with the economies of former colonies entering into trade and development deals that benefited Soviet capital accumulation. This process posed the most immediate threat to US imperialism, which explains, from the US bourgeoisie’s perspective, why it made a tactical alliance with China in the early 1970s even as, in the long term, genuine socialism at the time in China was a far bigger threat to US imperialism. But in the larger sense, Soviet political influence on anticolonial struggles and postcolonial governments strengthened bourgeois elements within them and pushed postcolonial economic policies beholden to foreign capital accumulation.

What has been called developmentalism, by contrast, claimed neutrality in the growing imperial rivalry between the US and the Soviet Union, playing the two off each other for better deals. Associated with the non-aligned movement, it was most possible in postcolonial countries such as Egypt, India, and Indonesia with coveted natural resources, a greater degree of industrialization than most former colonies, and/or large territories and populations. Its ideological and political attraction was the claim of independence, a claim increasingly undercut as virtually all developmentalist governments cut deals with international finance institutions and foreign banks for loans and with foreign corporations for capital. The main political problem with developmentalism is that it tried to dodge the basic question that has to be asked of any plans for economic development, namely, development for whom and for what, to take society in what direction? In a world in which capital accumulation is the dominant logic, not answering that question decisively in favor of the masses and the socialist transition to communism will inevitably mean development along capitalist lines within a global divide between imperialist and oppressed countries, whatever the intentions of the developmentalists, as the above descriptions of postcolonial industrial, agricultural, and infrastructure development have shown.

Answering that question in the way that Maoist China did meant a rejection of quick fixes. It resulted in being surrounded by hostile forces and required enlisting the population in a hard path relying on their own creativity, collectivity, and labor to use the resources available without depending on trade, capital, or technical expertise from outside. On that path, China had the objective advantages of a large population and territory, but the decisive factor was the subjective one—communist leadership and the conscious initiative of the masses—which was used to overcome difficulties like the lack of energy resources (they found oil, for example). Each former colony faced its own particular challenges, and while the Maoist path did not offer a blueprint for solving all those challenges, it did offer the right general principles.

In Africa, one challenge was that, as Walter Rodney summed up, “African nationalism took the particular form of adopting the boundaries carved by the imperialists. That was an inevitable consequence of the fact that the struggle to regain African independence was conditioned by the administrative framework of the given colonies.”65 Consequently, independent African countries emerged rich in some resources but lacking in others, and some only had small territories to draw resources from. In addition, colonial borders had drawn together people of different cultures, and colonial authority pitted them against each other and/or propped up one cultural group over others. The international bourgeoisie could use both these factors to their advantage, forcing independent African countries to depend on them, and the system of world trade they commanded, for resources they lacked and continuing the practice from colonialism of manipulating divisions between different peoples within state borders.

African postcolonial governments certainly pushed back, with Nkrumah increasingly advocating Pan-Africanism not just ideologically and culturally, but also as a strategy for bringing together different independent countries in part to overcome their individual limitations in resources and production capacities. In resolving internal differences between peoples and cultures, Tanzania under Nyerere’s leadership provided the best model, constructing a new culture that drew from and transformed the diverse array of traditions in its territory as well as incorporating from outside its borders, as can be seen in the way that state-sponsored culture encompassed everything from ngoma dance to taarab music to modern Chinese ballet. Consequently, Tanzania did not suffer the kind of so-called “ethnic conflict” that spiraled into brutal violence in neighboring countries.

The efforts of a number African postcolonial governments to overcome the legacy of imperialism and build various conceptions of socialism is a subject in need of deeper summation, especially from a communist perspective. One important theoretical question that experience raises is the fact that while nations are certainly historically constituted objective phenomena, they are historically constituted through subjective actions.66 As Walter Rodney pointed out, colonialism in Africa blocked the development of nations,67 so African nations were forged through the anticolonial struggle and its aftermath, often putting one culture and people in the dominant position within a given independent state (the Mandé in Guinea, for example). Unfortunately, the model of the multinational socialist state pioneered by the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China was not taken up elsewhere, which proved to be of great advantage to imperialism for fostering and inflaming national divisions within and between former colonies turned independent states in order to weaken and subjugate them.