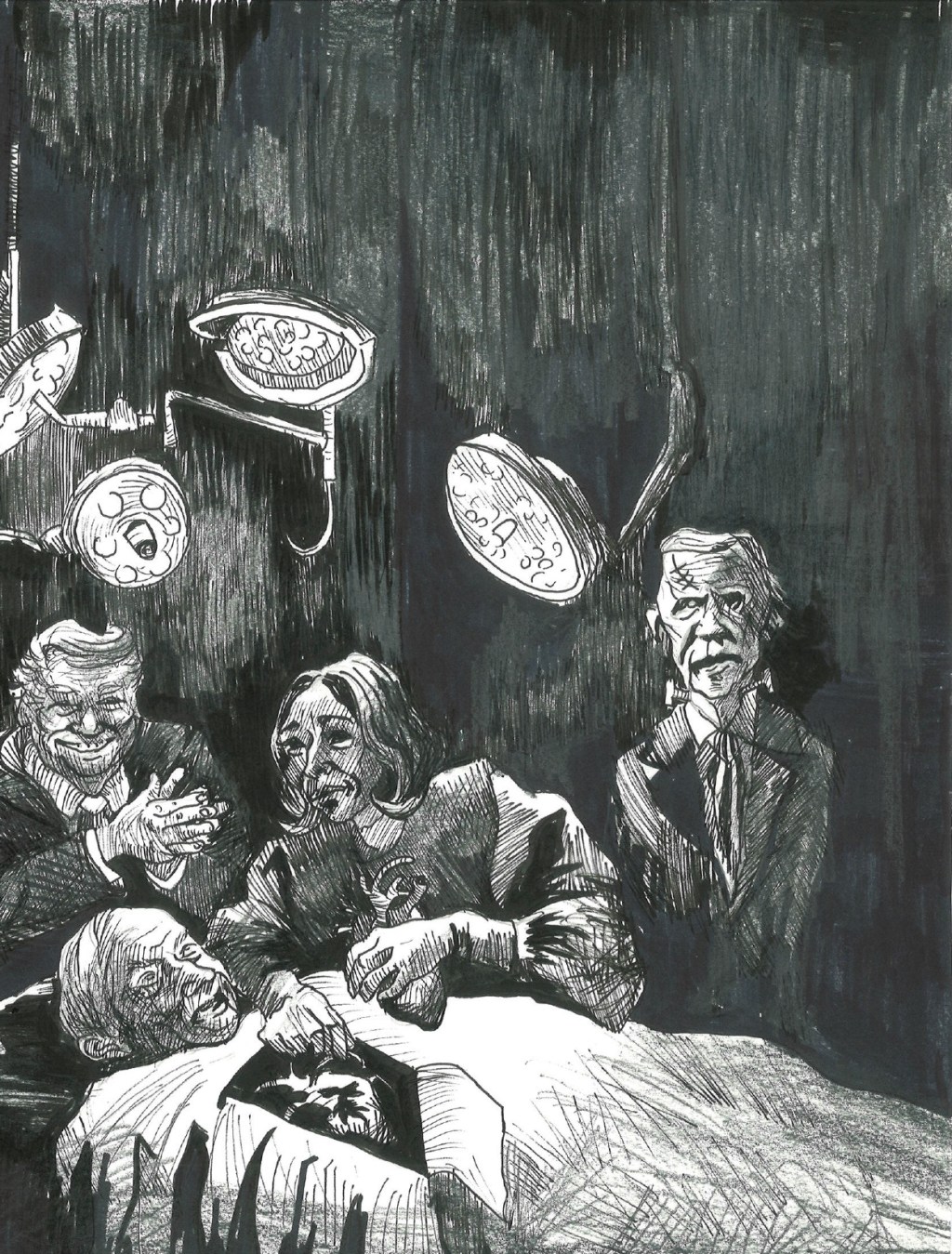

GATT editorial, November 2024

Every four years, the US bourgeoisie hosts a public referendum on which bourgeois program will be in the dominant political position for the next four years. These rituals, known as presidential elections, invite the people broadly to approve of—or acquiesce to—a set of policies shaped by the representatives of different segments of the bourgeoisie. They bring the popular classes into the fold of bourgeois politics, with pervasive media spectacles shaping their thinking and with individual members of the bourgeoisie using their wealth to tip the outcome in favor of their preferred candidate. Sometimes, the outcome of these contests is ambiguous or results in two contending programs locked in competition via who holds the legislative vs. executive branches. Occasionally, the outcome is outright contested and settled by arcane rules rooted in preserving the power of slave-owners (the Electoral College, as in 2016) or by fiat (the Supreme Court, as in 2000). This time around, however, there was no question that the restorationist program represented by Kamala Harris and the Democratic Party was firmly rejected by broad swathes of the US population, despite no shortage of bourgeois financial backing, media cheerleading, and firm support from a small social base. To understand that popular rejection, permit us to review what program Harris campaigned to restore and how various classes have come to resent it over the last several decades.

The delusional confidence of the Harris campaign was induced by decades of arrogant, out-of-touch triumphalism on the part of the Clintonian Democratic Party. Coming in on the coattails of US victory over Soviet imperialism in the Cold War, the Clinton administration of the 1990s consolidated the global capitalist order with the US bourgeoisie firmly on top. They furthered the elevation of finance capital into a dominant position of massive profit-making, enabled multinational corporations to profit from the superexploited labor of oppressed countries through outsourced production, and backed the rise of tech capital. Never mind the fact that letting finance capital run wild with speculation, free trade agreements (NAFTA, the WTO), and new, more flexible forms of exploitation undermined and even ruined the class position of large segments of the Democratic Party’s electoral base.

Clintonian triumphalism did not face its day of reckoning in the 2000s. Its true believers could fairly argue that the 2000 election was stolen, and the bourgeois program that entered after that election unquestionably proved to be a setback for US imperialism. The neocons at the helm of the Bush administration made an adventurist attempt to replace non-compliant regimes in Afghanistan and Iraq (with intentions for more of the same elsewhere), and were left with failed colonialesque governments in those two countries, popular discontent in the US over the costs of war and occupation (financially and in the lives of US soldiers), and rising rival imperialist and regional powers taking advantage of US troubles, with China and Iran as the chief beneficiaries. To top it off, finance capital’s profit through speculation—a continuity between the Clinton and Bush years— spectacularly collapsed, along with the housing market, in 2008, the last year of Bush’s presidency.

The entering Obama administration escaped any reckoning by virtue of being able to blame its immediate predecessors for the failures of the neocon program internationally and the wave of mass impoverishment and loss of home ownership domestically. What it offered was a Clintonian program with a few adjustments: more free trade agreements, rescuing and strengthening finance capital, and continuing to prop up tech capital and multinational outsourced exploitation. It adamantly refused to take action to reverse the downwardly mobile class position of many of its electoral constituents. Internationally, it practiced aggressive containment against imperial rivals and assertive regional powers, gleefully used the new technology of drone strikes for selective assassinations, and adopted a policy of supporting destabilization and civil war, sometimes including aerial bombardments by the US military, in North Africa and the Middle East to deal with regimes it could not control.

But the Obama administration had a thorn in its side from its first year in office: the revanchist petty-bourgeoisie. This ideological bloc, with small business owners at its core, refused accommodation within the established political rules, outright rejecting the legitimacy of Obama as president and questioning the constitutionality of his policies. Cohered politically into the Tea Party movement, with no shortage of funds and manipulation from reactionary members of the bourgeoisie and reared ideologically by addictive consumption to right-wing media, it was nonetheless a petty-bourgeois movement asserting its class interests, including against the Republican Party establishment. Its political representatives won Congressional seats and adopted a policy of wrecking existing bourgeois politics, programs, and procedures, embracing government shutdowns rather than ratifying federal budget deals. Not only did they untether themselves from the Bush years, but they also went on to discredit and push aside the old guard politicians of the conservative bourgeoisie, though a few remained as embattled stewards of a different ship than the one they boarded decades ago.

The wrath of the revanchist petty-bourgeoisie spearheaded the most successful movement “from below” during the Obama years, thoroughly repudiating the politics of the Clintonian Democratic Party, bending the Republican Party to its will, cohering an organized ideological bloc of tens of millions, and making its way inside the halls of power. But as the promise of “hope” that Obama offered proved empty, other classes erupted in struggle. At the end of the Obama years, Black proletarians broke out in rebellion, sparked by police killings but undoubtedly fueled by the fact that the first Black president had raised expectations for the Black masses and then failed to deliver any blows against the oppression of Black people.

Managing to sustain a more ongoing assertive presence, however, was a relatively new class, cohered as an ideological bloc over several decades and mounting the political stage decisively in 2011 with the Occupy Wall Street Movement: the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie. While it joined, opportunistically got to the head of, and even sometimes started many just protest movements, it is a reactionary class seeking to secure and advance its class interests and privileged position within the reconfigured capitalist-imperialist order. Unlike the revanchist petty-bourgeoisie, it seeks to adjust the Clintonian Democratic Party program to its benefit, not tear it apart. The postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie’s college-educated ability to make sophisticated critiques of that program, and its mobilization in, and leadership over, oppositional protest movements obfuscates its reactionary class nature, which rests on its well-paid, professional, and highly parasitic positions in ideological state apparatuses and the nonprofit industry.

As two reactionary petty-bourgeoisies aggressively asserted their class interests during the Obama years, the legitimacy of Clintonian Democratic Party politics became increasingly undermined for broad swathes of the US populace facing downward class mobility and destabilizing effects as a consequence of post-1970s capitalism reconfigured with finance capital in command. Failing to recognize this fact, in 2016, the Democratic Party picked a presidential candidate who most arrogantly embodied the Clintonian program and legacy—Hillary Clinton—while sabotaging the candidate—Bernie Sanders—offering an alternative bourgeois program that sought to restore the class position of sections of its traditional electoral constituents.

Even before the Democratic Party had officially crowned Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump seized the opportunity, revealing himself to be uniquely able to understand and mobilize the class frustrations of the revanchist petty-bourgeoisie and wider sections of the population, including the dispossessed formerly well-paid working class, peeling away many of the Democratic Party’s longstanding electoral constituents. The mass appeal of reactionary, fascistic, revanchist ideology and politics in the most powerful imperialist empire in human history is no surprise, and is especially enticing when delivered by someone who is no mere apprentice in the art of spectacle and entertainment. But the conjunctural conditions for Trump’s success were the failures, for the popular classes, of the Clintonian political program—the way it propped up the profits of finance, real estate, tech, outsourced production, and other capital at the expense of the privileged class position of broad swathes of the US population (not to mention the exploited and dispossessed in the oppressed countries). It was chickens come home to roost, and the Clintonian crowd was only caught off guard because of their arrogant triumphalism and their delusional distance from all but the upper echelons of the petty-bourgeoisie.

Trump’s refusal to play by the rules—rules so cherished by the Clintonian Democratic Party establishment—endeared him to the revanchist petty-bourgeoisie and tapped into broader frustrations with the established order. But it was also cause for consternation among the bourgeoisie, especially as his first administration became a revolving door with no shortage of cranks, and as policy became unpredictable given Trump’s erratic and ego-driven decision-making (for the record, Obama arguably had a bigger ego1). Nevertheless, for all his railing against elites and isolationist anger, on matters sacred to the American imperialist bourgeoisie in the 21st century, including finance capital’s pre-eminence and the US military’s ubiquitous presence around the world, differences between Trump and his presidential predecessors were minor matters. Brazen rhetoric and outerborough uncoothness could be overlooked when the bourgeoisie, including tech capitalists who leaned Clintonian, saw their taxes decrease and profits increase under Trump.

It was the COVID pandemic that brought the instability of the Trump administration back into bourgeois anxiety, especially as the liberal petty-bourgeoisie, the primary social base of Clintonian politics, perceived Trump’s response to the pandemic as an existential threat to its existence. The widespread participation of the liberal and postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie in the Summer 2020 protests sparked by proletarian rebellions against police brutality in turn boosted the political energy to channel ire at Trump into the polls. Ultimately, most members of the bourgeoisie abandoned Trump by Summer 2020, resulting in a shortfall of donations and a lack of political operators in his camp that consigned his re-election campaign to defeat. For the top beneficiaries of capital accumulation, knowing the empire is being run smoothly and predictably, with minimal turbulence, is worth more than whatever short-term profit could be made with a Trump presidency. As Trump’s bourgeois backers jumped ship, the revanchist petty-bourgeoisie stayed on board the sinking vessel, with a younger, perhaps more reactionary cohort not only staying afloat but scoring electoral victories, especially in the House of Representatives. Nevertheless, the hardcore revanchists failed to win over the broader layers of support required to keep the presidency in their corner.

In the realm of bourgeois politics and from the perspective of bourgeois class interests in Fall 2020, Joe Biden was the perfect candidate to unseat Trump not only for his proven track record as a steward of bourgeois stability and centrism, but even more so because he may well be the last pre-Clintonian Democratic Party leader in existence. As such, Biden could undercut Trump’s appealing assault on the Clintonian establishment. Even with a long record of serving bourgeois interests in general and Delaware-based credit card companies in particular, Biden is a Democrat cut from a pre-1990s mold who could credibly claim he would be a pro-union president. The post-World War II, pre-1990s Democratic Party rested on an alliance with the union bureaucracy, with the latter bringing the well-paid working class into the Democratic fold as a reliable voting bloc. Biden’s political career got started when that alliance was still strong, and his pre-Clintonian credentials gave him the ability to win back sections of the well-paid and dispossessed working class whose class position had been undermined by the Clintonian program. That advantage, however, was never made good on programmatically. Some union-friendly personnel were appointed to the National Labor Relations Board, and there were some small attempts at regulation and job creation at the beginning of Biden’s term, but the benefits of a Biden presidency for the well-paid and dispossessed working class were never more than a pittance.

Towards the end of the Biden administration, an avalanche of destabilizing contradictions, from the burden of inflation on the homefront to Israel’s unhinged genocidal war on Gaza, together with Biden’s deteriorating mental faculties, delegitimized his presidency for different sections of the population and for different reasons, some righteous and some reactionary. Even before those centrifugal forces asserted themselves, there was little material basis or bourgeois support for a Bidenist radical reorientation away from the Clintonian legacy. Moreover, the Biden administration stopped short in efforts to discipline and punish Trump for his attempts to subvert his 2020 electoral loss, leaving him the freedom to mount a comeback. The Biden adminstration also failed to reverse key losses of bourgeois-democratic rights, such as the right to abortion, giving little confidence to even its remaining base of support that four more years would deliver them to a liberal bourgeois-democratic labor-friendly promised land.

The last minute panicked attempt to switch Biden with a more viable candidate proved worse, for the liberal bourgeoisie’s desired outcome, than what it sought to replace. The Harris campaign leaned hard into articulating a restorationist program, promising a return to Clintonian stability that only the liberal petty-bourgeoisie was buying. Aging out, lacking any dynamism, and morally bankrupt by its acquiescence to genocide, the liberal petty-bourgeoisie’s alarmist hysterics about the threat of fascism and Manchurian candidate conspiracy theories about Putin’s grandiose authoritarian ability to manipulate Trump only served to turn other classes off from Harris. The sacred bourgeois-democracy that the liberal petty-bourgeoisie imagines itself to be defending has already been profaned, among other things by the selective repression of the right to free speech in police crackdowns of anti-genocide protests on college campuses, most of which were carried out on the orders of representatives of the liberal bourgeoisie. But all Harris could offer was a defense of profaned liberal bourgeois-democratic principles to a shrinking congregation in a church that no longer cared for the poor, having (metaphorically) eliminated its soup kitchens in the 1990s with Bill Clinton’s promise to “end welfare as we know it.” Worse yet, Harris supplanted liberal bourgeois-democratic values with sops to the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie’s out-of-touch identity politics, believing that oppressed people think like the privileged elites who speak in their name and alienating oppressed people in the process. As if all that was not enough to alienate everyone but a couple upper sections of the petty-bourgeoisie, the Harris campaign broadened and doubled down on its restorationist program by rehabilitating the neocons of the Bush administration, touting Dick Cheney’s endorsement and trotting out his daughter, Liz, as its cheerleader. Under Harris, the content of I’m-not-Trump restorationism was made worse than the Clintonian Democratic Party alone by encompassing the Bush Republican Party.

The electoral defeat of Harris was a reactionary repudiation of the Clintonian Democratic Party’s program, a program it has clung to for three decades. On a personal level, we are happy to see the horrific, imperialist legacies of Clinton, Obama, Biden, and all the bourgeois functionaries that served in their administrations burned and their namesakes die knowing few will mourn them. But we are under no illusion that the fire this time is paving the way for anything other than a different bourgeois program to come to the fore. Nor will capitalism-imperialism as it has been reconfigured since the 1970s transform in any ways that fundamentally benefit the masses. In any event, the die is cast, and it seems unlikely that the liberal bourgeoisie can successfully rehabilitate Clintonian politics in 2028, though they may well try to owing to their arrogance and lack of innovation. We shall have to see what is in store in the coming years and adapt our strategy and tactics as the contradictions unfold. What we can do now is understand how various classes in the US have been shaped by, and shaped, the unfolding of recent events and what that tells us about who are our friends and who are our enemies.

For communists, answering the question “who are our friends, who are our enemies?” means making a class analysis, examining the material class interests, aspirations, and motion and development of the different classes in society and how they stand in relation to each other. Too often, class analysis is understood, by people who claim the mantle of communism or Marxism, as a rather mechanical look at occupations, incomes, and direct relationship to the means of production to place percentages of a given population into static categories. While there is a point to looking at economic demographics, in what follows, we will be analyzing how classes are moving in relation to the unfolding contradictions of capitalism-imperialism, how new and established classes assert their class interests and aspirations, and how historically outmoded classes lose their position or fade from existence. We will also be analyzing classes—especially distinct sections of the petty-bourgeoisie—as ideological blocs that more or less correspond to economic positions, but with plenty of messiness. In doing so, our method of class analysis will be something like a synthesis of Karl Marx’s The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte with the television series Deadloch and the observations of stand-up comedians. We will also be drawing from analysis by academics and journalists while keeping the citations light, and, most importantly, the experience of the communist movement in the US.2 That movement is exceedingly small at the moment, but it is punching well above its weight and learning, through its political work, where different classes are lining up in relation to the (potential) struggle for power between the two classes capable of running society: the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

As we see it, the main social actors driving the political drama on stage after 2008 have been two reactionary classes: the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie and the revanchist petty-bourgeoisie. In this political drama, the big bourgeoisie, concentrated as heads of finance capital and multinational corporations of a new type but including other kinds of capitalists, own the theater, and because their ownership of the theater is not really contested at present, they are okay with letting those two reactionary classes seize the spotlight during performances and even letting them influence the repertoire performed. Other classes, such as the liberal petty-bourgeoisie and the well-paid working class, are season ticket holders who have some say over, and differing opinions about, what plays out on stage. The proletariat, not invited into the theater, has been able to bum-rush the show a few times, but has yet to write the script or get more than a one-off production on stage. And that is what we seek to change.

Two reactionary petty-bourgeoisies get brazen and bold

In imperialist countries today, the petty-bourgeoisie is a large portion—perhaps a majority—of the population, but is divided into different sections based on their relationship to the means of production, such as small business owners of various types and college-educated professionals working in skilled mental labor occupations. In the US, to speak of “the petty-bourgeoisie” without specifying which section is a relatively worthless exercise, and specific sections are more easily, or more revealingly, broken down by ideological blocs than occupations.

Much of the time in imperialist countries, the petty-bourgeoisie as a whole is content to let the bourgeoisie rule, so long as it gets to register its approval or complaints in well-staged rituals (bourgeois elections). In revolutionary times, some segments of the petty-bourgeoisie may break out in revolt and stand with the masses (the student movements of the 1960s, for example), even if in contradictory ways. When capitalism-imperialism is undergoing, or has recently undergone, transformations that put petty-bourgeois class positions up for grabs, upper sections of the petty-bourgeoisie—old and new, established and aspiring—feel compelled to assert their agency to secure and advance their class position, and are often given wide latitude to do so. In asserting their agency, sections of the petty-bourgeoisie constitute themselves as distinct ideological blocs, defined by their worldview and political allegiances, which, over time, get consolidated into the functioning of bourgeois-democracy.

Other class fractions, of the lower petty-bourgeoisie and working class, are generally only permitted, and only desire, a more passive role in bourgeois politics, or are mobilized into a more active role by the bourgeoisie when it needs to (usually for war and/or fascism—Nazi Germany was both a brutal fascist dictatorship and a highly participatory society, as is Israel today). These class fractions will receive lesser attention in the following analysis given their more passive role, relative to two reactionary sections of the petty-bourgeoisie, in recent events. We will touch briefly on the ideological and political disposition of the well-paid working class and its now dispossessed segments, as well as what we might call the broad lower middle—members of the upper proletariat and lower petty-bourgeoisie working in semi-professional, clerical, and service occupations. Our point, with these class fractions, is not to present a comprehensive analysis of all classes in society, but to probe where the class-conscious proletariat can seek out allies and peel people away from bourgeois, or reactionary petty-bourgeois, hegemony. But the main focus in what follows are the two reactionary petty-bourgeoisies whom the class-conscious proletariat needs to sweep aside.

The postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie: an archaeology or a genealogy (whatever the fuck the right Foucauldian gibberish is) of a reactionary class

A source of tremendous confusion and demoralization over the past decade has been the assertive existence of a growing class that presents itself as a proponent of struggles for social justice but is bitterly hostile towards revolution and utterly contemptuous towards the masses. Here, we hope to clear up the confusion and combat the demoralization by outlining the formation of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie and explaining what makes it a reactionary class, despite its deceptive appearance. Its formation began in academia, so we start our story there.

The post-World War II expansion of the US university system broadened the ranks of college professors, a privileged upper petty-bourgeois class position. The new generation that entered that profession after the 1960s, especially in the humanities and social sciences, secured its class position by fighting a two-front battle. On the one hand, it displaced the bourgeois ideologues who had dominated the professoriate by critiquing them as outmoded and conservative—out of sync with the social movements and cultural transformations of the 1960s. On the other hand, it beat back the impact of the revolutionary movements of the 1960s on the universities by repudiating radical politics of all stripes, from Marxism to revolutionary nationalism to (eventually) second-wave feminism, with a new ideology: postmodernism. This move was crucial to its legitimacy, as many of those entering the ranks of the professoriate in the 1970s and 1980s were either former radicals turned sellouts or were culturally part of the 1960s but lacked the arrest records of real revolutionaries, so they had to prove themselves in the realm of discourse.

Conveniently, their new ideology came wrapped in obfuscation, propagated in academic writing drenched in obtuse jargon and stylistically obsessed with sounding profound while lacking in substance. Nevertheless, as Timothy Brennan explains in his book Wars of Position: The Cultural Politics of Left and Right (Columbia University Press, 2006), there was a clear turn towards an orthodoxy based on a “shared canon of venerated texts” among professors in the humanities and social sciences in the 1980s and 1990s, with the work of French philosopher Michel Foucault a foundational part of that canon. We have polemicized extensively against postmodernist ideology and politics from kites #1 through Going Against the Tide, and we suggest readers also study Brennan’s book for an intellectual history of postmodernism. What stands out about postmodernist ideology, from the perspective of class formation, is its obsession with endless but toothless critique of existing and historical power relations alongside a rejection of making demands on, let alone seeking to overthrow, the existing state power that defends those power relations. In addition, postmodernist ideology largely rejects analysis of exploited classes, oppressed nations, and (eventually) the subjugation of women to patriarchy in favor of the nebulous concept of “difference” in opposition to impositions of “normativity.” It displaced discussion of material relations of exploitation and oppression with an emphasis on identity and the realm of ideas—in its nomenclature, “discourse”—the precise realm in which the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie makes its money.

Postmodernist ideology became orthodoxy in academia by virtue of the fact that its proponents secured dominance over many academic departments and disciplines, some entire universities, and numerous academic journals. Academic hiring committees and academic peer review became means for expanding its class and discursive dominance within the university system and intellectual life. If that was as far as the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie advanced its class position, we probably would not be devoting so much time to understanding it as a class. But it did not stop there. From its position as university professors, the emerging postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie expanded its class power by applying a sort of tactical Leninism-Gonzaloism. It propagated its ideology in college classes and trained up new adherents who could then go on to secure class positions outside academia, transforming existing petty-bourgeois professions and populating new ones.

Key among those new professions was that of nonprofit-sector activist. As a preventive counterrevolutionary measure in the wake of the 1960s revolutionary movements, nonprofit organizations were bolstered with bourgeois philanthropic funding and propped up to displace radical and revolutionary organizations. They developed clientelistic relations with the masses, advocating for “social justice” on behalf of the masses while being unaccountable to them. The Democratic Party, in turn, developed clientistic relations with many nonprofit organizations. And, crucially for the expansion of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie as a class, nonprofits siphoned college-educated youth, from the petty-bourgeoisie and proletariat, into professional positions as activists, advocates, and organizers who could critique injustice and put band-aids on it while never mobilizing the masses in class struggle. Over the course of the 1980s and 1990s, nonprofit-sector activist became a viable petty-bourgeois career path, so long as one adhered to the postmodernist ideology and politics that came to dominate nonprofit activist organizations—in short, so long as you became part of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie as a class.

In addition to the burgeoning nonprofit activism industry, as an ideological bloc, from the 1990s up until today, the college-trained postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie gained significant or dominant positions within journalism, education, arts and culture institutions, the entertainment industry, and other mental-labor professions that produce culture and discourse. It also served the bourgeoisie in modes of capital accumulation that required large numbers of professional intellectual workers, such as tech capital. In some instances, the rise of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie was a generational and ideological displacement of the liberal petty-bourgeoisie that had previously dominated the professions in question. In other instances, such as in tech capital industries and nonprofit organizations, fractions of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie were created or grew dramatically as a consequence of transformations in the economic and political operations of capitalism-imperialism. For example, the Clinton administration pioneered a new approach of “governance” that was furthered under Obama, where the bourgeois state implements policies by way of partnerships with nonprofits, media and social media companies, and assorted private enterprises, even including banks.3 The postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie seized on opportunities created by the overall framework of governance to carve out well-paid bureaucratic positions that often serve the purpose of enforcing its ideology and politics. The most well-known among these positions are at Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion offices at colleges and their counterparts in private companies, which have largely proved to be performative entities that fail to transform the inequalities they were supposedly created to combat.

The postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie’s seizure of existing well-paid professional positions and securing of new ones took place as capitalism-imperialism increased cutthroat competition for jobs, with massive cuts to social spending throughout the 1980s and 1990s and the privatization of many functions previously carried out by the bourgeois state while production and trade were reorganized around the superexploitation of the labor and resources of the oppressed countries. In the 2000s, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie emerged as one the victors in that competition, whether that was by way of nonprofit organizations receiving funding to take over formerly government functions or tech capital sharing some of the profits of offshored exploitation with its intellectual workers.

While securing its class positions, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie had yet to assert itself politically except in the realm of intellectual and cultural critique and nonprofit-sector activism. In fact, one of the defining features of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie is its desired distance from bourgeois state power. It studiously avoided running candidates in its mold for office, happy to let the liberal bourgeoisie govern. It stayed largely on the sidelines of mass struggles through the early 2000s, at best taking part as passive participants, with its political cadre preferring nonprofit advocacy work to militant resistance. From the 1980s to the early 2000s, resistance movements in the US were led by ideologies ranging from anarchism, the remnants of 1960s revolutionary nationalism, revolutionary communism, Trotskyism and revisionism, to reformism of genuine and opportunist varieties. Postmodernist ideology and politics did start to encroach on resistance movements and began to degrade some of the aforementioned ideologies, but the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie had yet to decisively mount the political stage, except by way of critique largely confined to academic discourse and entirely divorced from political struggle. The postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie waited until the 2010s to mount the political stage, by which point it had staked out its geographic territory and added to its ranks through a cultural movement drenched in decadent individualism and hostile to political and social commitment.

The hipster phenomenon of the 2000s placed recent graduates of upper-tier colleges—the new ranks of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie—as creative agents in a new wave of cultural production, ostensibly “bottom up” but in reality orchestrated by fashion, music, art, and media capitalists.4 The aesthetics of ironic detachment bound up with hipster culture, from fugly fashion to mediocre indie-rock to hedonistic parties, betrayed the fact that its participants gleefully looked the other way as photos of torture and news of massacres perpetrated by the US military in Afghanistan and Iraq circulated. Beyond its disgusting apathy in the face of imperialist horrors, hipster culture accomplished important advances for the class position of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie. It ideologically elevated parasitic lifestyles, even celebrating them as radical chic when drenched in subcultural capital. It trained the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie in the art of faking expertise and asserting intellectual and cultural authority, using what they learned at college and through cultural consumption to pose as arbiters of art and style, a skill they later transferred to politics. That fake expertise included appropriating styles and symbols from previous rebellious cultures, from punk to rap to avant-garde jazz, a skill likewise later transferred to appropriating the aesthetics of past and geographically distant revolutionary political movements. It also taught the upper echelons of the petty-bourgeoisie to fake a lower class position, whether through donning the styles and beer preferences of lower classes or by hiding their access to family wealth while “slumming it.”

But perhaps the most important contribution of hipster culture to advancing the class position of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie was its crucial role in consolidating a transformation of social geography. Beginning in the 1990s, ramping up in the 2000s, and continuing thereafter, hipster twenty-somethings moved en masse into neighborhoods that had been laid to waste by the flight of industrial capital and the loss of jobs for their proletarian inhabitants. From Brooklyn to Oakland and virtually every city in between, proletarians were pushed out of their historic neighborhoods, with an initial wave of petty-bourgeois “slumming it” giving way to rising rents, condominium construction, and policing policies protecting the newcomers and repressing or kicking out the dispossessed. What is commonly called gentrification was a reactionary (geographic) movement by the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie against the proletariat, in league with real estate capital and the bourgeois state. Ironically, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie later began railing against “settlers” despite being the closest thing to them in the present-day US.

In addition to evicting proletarians from their historic neighborhoods, the hipster transformation of social geography also set the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie apart from its parents, the liberal petty-bourgeoisie, a class that had left cities for the suburbs as part of securing its class position decades earlier. Furthermore, it paved the way for a new postmodernist petty-bourgeois class position, namely small business owners and service providers setting up shop in the urban territory that its class compatriots had conquered. Unlike other petty-bourgeois shopkeepers in urban centers, postmodernist petty-bourgeois proprietors only serve their class brethren, with the cultural value of the products and services they sell, and their exorbitant prices, locking the proletariat out of their stores.

What provoked the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie to get up from the armchair of critique in academia, to sober up from the Brooklyn warehouse party of ironic detachment, and mount the political stage in the 2010s? The 2008 financial collapse constricted job opportunities for recent college graduates across many sectors of the economy. Beyond that conjunctural event, the structural conditions of a reconfigured capitalism-imperialism both benefited and threatened the class position of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie. Some of its members advanced their careers in growth industries (tech, for example), did well navigating the flexible employment conditions of the gig economy, or secured grant funding for their cultural endeavors. Others, however, faced downward mobility as tenured professor positions were replaced with adjunct instructors, journalism job opportunities dried up when established companies struggled with the decline of print media, and publicly-funded institutions went broke under budget cuts. So, when the Occupy Wall Street movement tapped into mass anger at the bailout of banks amid widespread downward class mobility and took off in Fall 2011, among those drawn to it were young class aspirants of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie.

Myth has it that Occupy Wall Street was a decentralized, leaderless movement. Reality is that beyond the silly, performative consensus rituals, the leaders and decision-makers at Occupy encampments were, for the most part, graduates of elite colleges trained in postmodernist ideology and politics.5 They constituted themselves as a cadre of sorts to fight for the class interests of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie in Occupy Wall Street and many other subsequent mass movements, using their mastery in the art of critique to define the discourse and thereby exercise hegemony over other classes involved. A key part of their strategy, conscious or not, has been to studiously avoid making militant demands on the bourgeois state, even rejecting the just demands of the masses. Instead, they create spectacles of protest, a hallmark of which is obsession over identity questions, through which to build their social justice credentials, which they then use for cultural clout, funding for their ongoing “activism,” or to secure professional petty-bourgeois careers.

Whereas Occupy Wall Street provided the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie with a crucial learning experience in asserting its class interests and aspirations over other class and political forces involved in the mass movement, a few years later it displayed its mastery of the art of hegemony. As Black proletarians rose in rebellion against police killings, first in Ferguson and then in Baltimore, social media savvy, nonprofit-sector trained members of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie articulate in the art of critique jumped to the head of the mass movement while their class compatriots more broadly overwhelmed proletarian rebellion with petty-bourgeois mass protest. To call Black Lives Matter the bourgeoisie’s co-optation of proletarian rebellion would be to miss the reactionary initiative of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie in hijacking the mass movement for its own narrow class interests. The success of the hijack is evident in the massive funds and plethora of privileged job positions created for the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie over the last decade while Black proletarians continue to face unabated police brutality. The liberal bourgeoisie, via its politicians, media companies, philanthropic foundations, and corporate branding, certainly recognized the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie as a class it could partner with, whose political representatives it could prop up as spokespeople for the broader movement against the masses who sparked that movement. Nevertheless, the reactionary initiative that diverted the mass movement away from revolution came not from the liberal bourgeoisie, but from the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie.

Over the course of the 2010s, young, politically active members of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie took the theory they learned in college as critique and turned it into praxis. Foucauldian power relations became not a description of society but strategy and tactics for careerism and opportunism. Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital became all too material in the most cynical way imaginable, with knowledge of postmodernist jargon used to seize the spotlight in discursive struggles and audition for well-paying professional occupations and grant funding. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s intersectionality went from a legal strategy for discrimination lawsuits to a way to credentialize, monetize, and rank identity. Whatever the intentions of the theorists (Bourdieu was not really a postmodernist), these and other concepts entered the petty-bourgeois professional world of cutthroat competition.

Based on its ideological work over decades from entrenched positions within ideological state apparatuses such as universities, training in nonprofit-sector activism, and class comfort in asserting its expertise and moral superiority, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie was able to fight for hegemony, consolidating its ranks and exerting discursive influence over other sections of people. In popular culture, this process is referred to as society becoming more “woke.” However, wokeness is simply a broader expression of the fact that the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie’s political representatives have been able to seize the initiative, in a succession of mass protests and political, social, and cultural movements, though not without contention and collaboration with other class forces.

For a few months after Trump’s victory in the 2016 election, the liberal petty-bourgeoisie took the uncharacteristic step (for itself as a class) of mass political action outside the electoral arena when it perceived an existential threat to the bourgeois-democratic principles it lived by. Given the class proximity and overall convergence of interests between the liberal and postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie, the latter was okay letting the former take the reins for a bit while using the opportunity to bend the liberal petty-bourgeoisie towards the postmodernist world outlook. There was certainly some tension between these two adjacent and overlapping classes, but an overall non-antagonistic tension.

Whenever the proletariat broke out in rebellion, as it did most powerfully in Summer 2020 in response to the police murder of George Floyd, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie mobilized hot on its heels, seizing the media spotlight and using the opportunity to garner more funding and job opportunities from the liberal bourgeoisie. In fact, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie made its greatest gains as a class in the aftermath of Summer 2020, with hundreds of millions of dollars flowing into nonprofit activist organizations and postmodernist academic centers; postmodernist ideologues such as Robin DiAngelo and Ibram X Kendi becoming rich celebrity Rasputins whispering into the ears of the liberal bourgeoisie; new job opportunities opening up for the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie in ideological state apparatuses, private companies, and government bureaucracies; and the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie capturing positions within and even control over arts and culture institutions, corners of the entertainment industry, media, and elsewhere. The proletariat was only able to briefly seize the initiative in powerful but all too short rebellions, facing police repression, not invited to speak for itself in the mainstream media, lacking access to financial and organizational resources, and left politically unprepared to realize its potential power due to the lack of revolutionary forces over a period of decades.

This reactionary Foucauldian gibberish is a pain in the ass; we gotta liquidate the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie as a class!

The postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie’s feeding frenzy for funds and professional occupations in the wake of Summer 2020 was something of a smash and grab operation, a specific opportunity that has since passed. The advances it made are often painted by right-wing ideologues as “diversity hires.” In truth, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie is a multinational but majority white class, which often uses people with the right “identity credentials” (i.e., people of oppressed nationalities, or, in postmodernist parlance, “BIPOC,” and people of non-normative genders and sexualities) as the public face of its quest for class advancement. Some members of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie from oppressed social groups have certainly done well for themselves over the last few years, without raising up proletarians from those oppressed social groups even an inch. But most of the beneficiaries of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie’s post-2020 feeding frenzy have been white members of its class.

Even as some of its more embarrassing behavior—its naked careerism and out-of-touch elitism—has been exposed, and its gains have been rolled back slightly, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie remains deeply entrenched and has been able to assert its reactionary class interests in mass movements after 2020. For example, when protests erupted against the Supreme Court’s move to overturn Roe v. Wade in 2022, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie tanked the short-lived mass movement by bizarrely insisting that it was wrong to make the oppression of women the central question in relation to the right to abortion.6 We could cite more examples of the reactionary actions of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie, and we suggest reading Musa al-Gharbi’s We Have Never Been Woke: The Cultural Conditions of a New Elite (Princeton University Press, 2024) for some damning exposure. But let us move on to summing up what about the class interests and ideological disposition of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie makes it a reactionary class.

The postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie is among the most parasitic classes in human history. It performs virtually no material production or physical labor, largely relegating itself to intellectual and cultural work in professions that are often highly individualized, and is for the most part on the upper end of income in the US. In its most coveted positions, the discourse and culture that it produces are more often than not of little intellectual or artistic value. Seriously, try reading a book by a postmodernist academic and more often than not you will find little of substance and not much in the way of research, but lots of gibberish and a circular and performative engagement with postmodernist theory.

The postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie’s parasitism rests on four broad categories of private appropriation. (1) Its privileged class positions are propped up by the superexploitation of the oppressed countries, directly in the case of the tech industry, where the divide between intellectual workers in the imperialist countries and the proletarians working in electronics manufacturing in Asia and mines in Africa is stark, but indirectly more generally by virtue of consumption habits and salaries fattened by the spoils of imperialism. (2) It secured and advanced its class position through the dispossession and displacement of other classes, particularly the urban proletariat, and by appropriating from the cultures and political movements of the oppressed for financial gain. (3) In some of its endeavors and occupations, its salaries come from grant funding and philanthropic donations from the bourgeoisie, thus getting a portion of the private wealth accumulated through the exploitation of the proletariat in order to produce substandard art and self-serving discourse or run orthodox cultural institutions and parasitic nonprofit organizations. (4) It advocates for and benefits from the gutting of public services and government agencies and the privatization of functions they were responsible for, most often via the burgeoning nonprofit sector. In this respect, “defund the police,” when presented as a practical, not just rhetorical, demand, always meant siphoning tax dollars away from police budgets and into the coffers of the nonprofit activist organizations. A truly radical slogan would be “defund and abolish the nonprofits!”

On the basis of and to protect its parasitism, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie has advanced a whole host of reactionary ideological and political positions against the masses while presenting them as virtuous and even liberatory. It has upheld the sexual exploitation of women and girls by discursively defending the sex trade, with the reactionary slogan “sex work is work.” It has used a nebulous notion of “abolitionism” to reject the just demands of the masses that killer cops be sent to prison. Indeed, it is more concerned about “carceral thinking,” which it considers a discursive sin of the most unholy variety, than the masses unjustly locked up in prison or the freedom of killer cops. It has constructed a relationship to the exploited and oppressed akin to “benevolent” colonialism, inventing idealized pictures of how oppressed people are supposed to think and act and then disciplining and punishing them when they step outside of the frame. For example, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie turned “white-passing,” a term originally used to describe light-skinned Black people who could sometimes get around the legalized segregation of the Jim Crow South, into an insult to question the validity and humanity of Black, Latino, and Arab people with a light complexion (in actuality, usually because the “white-passing” individuals disagree with or get in the way of postmodernist ideology and politics). The postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie often blames oppressed people for the oppression of other oppressed people, for example, using the term “anti-blackness” to blame Latinos and Asians, rather than the bourgeoisie, for the oppression of Black people. The postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie replaced the old liberal petty-bourgeois racist stereotype of Black proletarian men as criminal, predatory threats with a new racist stereotype of Black proletarian men as misogynistic, homophobic, and transphobic. In these and other ways, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie displays a hostile attitude towards the masses that ranges from lack of concern for their conditions to contempt for their existence, all while mastering ever more esoteric and performative discourse about oppression and identity.

In addition to its reactionary disdain for the masses, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie has reneged on the one progressive political role that sections of the petty-bourgeoisie have historically played, namely defending bourgeois-democratic principles and bourgeois-democratic rights. A telling example is the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie’s failure to defend transgender people from attacks by the revanchist petty-bourgeoisie and its allies in government positions. Trans rights are fundamentally bourgeois-democratic rights, from equal treatment before the law to privacy and self-determination in healthcare to equal access to public services to being free from discrimination. The enactment of state laws against trans people are fundamentally attacks on trans people by way of attacks on their bourgeois-democratic rights. Trans people also face bigotry and bias, and trans proletarians—whether born into the proletariat or dispossessed into it as a result of fleeing from, or being kicked out by, reactionary parents, laws, and places—face the poverty and exploitation all proletarians do in addition to anti-trans bigotry, discrimination, and violence. Securing bourgeois-democratic rights for trans people will not, in and of itself, overcome anti-trans bigotry and bias among the people, nor end exploitation, but those rights are a necessary basis for doing so. However, instead of leading a mass movement for the bourgeois-democratic rights of trans people, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie has decided to make pronoun circles and other discursive questions the hill it is willing to diatribe on, leaving trans people in Florida, Texas, and elsewhere, especially the proletarians among them, to fend for themselves while facing the state-sanctioned, legalized anti-trans onslaught.

Beyond its performative stand with and practical abandonment of trans people, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie’s animosity towards bourgeois-democratic rights is used to exert its discursive dominance, push aside potential competitors with its class power, and throw the masses and revolutionaries under the bus. This takes shape most palpably around its rejection of free speech and constitutional protections. The postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie frequently wages campaigns to “cancel” viewpoints and people it perceives as a threat to its class interests and smug self-righteousness, whether through social ostracization, discursive mass campaigns, or direct calls for government agencies, universities, and private companies (such as streaming services) to censor aberrant ideas and those who articulate them. To be clear, us communists do not believe in free speech without any limits, and outright reactionaries and counterrevolutionaries will not be allowed freedom to spread their ideological poison via mass media and public forums in socialist society. But we certainly do not advocate, in the future socialist society, the level of groupthink and censorship that the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie celebrates and seeks to impose today. Moreover, we find the bourgeois-democratic principle of free speech an overall strategically favorable condition for the proletariat within bourgeois society. We are not defenders of the right of fascists to free speech, but we are also not going to unite with the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie’s attempts to censor viewpoints and people who defy its discursive domination. When it comes to depriving the present-day spokespeople of reactionary movements of their platforms, we prefer to do it the old fashioned way rather than by begging the bourgeoisie to censor them.

Unlike the liberal petty-bourgeoisie, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie cannot be an ally of the proletariat in struggles defending bourgeois-democratic rights. In addition to lacking bourgeois-democratic principles,the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie is a reactionary class by way of the grotesque opportunism and careerism it uses to advance its class position. Not only does nepotism and corruption run rife in the institutions the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie has captured, but this reactionary class has mastered the art of using the revolutionary energy of the masses and the legacy of past revolutionary movements for its own (financial) gain, as we have documented above. This makes it a dangerous class to the proletariat, full of hostility to revolutionary politics precisely because genuine revolutionary politics and practice expose the careerism and opportunism on which the class position of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie rests. Consequently, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie is the class most willing to snitch on revolutionaries and sabotage the development of a revolutionary mass movement.

In addition to its reactionary role in the present, we must also recognize that the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie would be at best useless under socialism and at worst harmful to it. Given its entrenchment in cushy jobs and parasitic lifestyles, it would become a reactionary bulwark against the step-by-step overcoming of class divisions under socialism. Much of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie works in the ideological state apparatuses, and would have to be largely banned from doing so under socialism so as not to spread poisonous ideological weeds. Others work as dispensers of social welfare (via nonprofits), and given their condescending attitude and clientelistic relationship towards the masses, they would have to be barred from any similar role in socialist society. More dangerously, since the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie is capable of organizing protest movements and has lots of experience asserting its class interests in radical-sounding political language, it is well positioned to undermine the dictatorship of the proletariat, even as it is unlikely to take up arms. At the same time, the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie excels at using whatever political lingo is in vogue for careerist purposes, so some members of it could quickly change their outer discursive appearance after the revolution to integrate themselves into socialist government structures for careerist purposes, thereby becoming the seeds of a new bourgeoisie within socialist society.

Given these realities, after the revolution, the proletariat will have to exercise dictatorship over the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie much like it does over the overthrown bourgeoisie, which could result in swelling the number of inmates in labor camps under socialism to unsustainable levels. This is a problem that the masses and the vanguard party will have to creatively solve, possibly by encouraging or forcing a mass exodus of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie from socialist territory, or perhaps by designating territory in New England and/or the Pacific Northwest as demilitarized autonomous zones for the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie to live in and govern itself. One advantage of this scenario is that it would make for good “PR” for the dictatorship of the proletariat, as postmodernist autonomous zones would enact far more censorship than the proletariat in power ever has, and would likely ban stand-up comedy outright. Eventually, however, the socialist state might be morally obligated to deliver humanitarian aid to the postmodernist autonomous zones when they inevitably fail to produce necessities for themselves and keep basic infrastructure running (they are only capable of producing discourse, after all).

But all that is a question for the future. For now, the crucial thing for communist cadre and class-conscious proletarians to understand is that the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie is a reactionary class that cannot be trusted, and our political efforts today should aim to undermine its political power and organizational strength and discredit its ideology. In short: repudiate postmodernism as a discursive formation and liquidate the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie as a class.

Splits in the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie

Fortunately for the proletariat, reactionary classes, especially the larger they become, are rarely monolithic. Splits within the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie occur along generational and economic lines, and then impact the political actions different members of this class take. The conditions in which the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie formed as a class include greater precarity of employment, with the reduction of privileged positions in many of its preferred occupations, competition for grant funding, and hustling in the gig economy. For example, the professoriate is now split between a smaller portion of tenured faculty and a larger mass of contingent instructors, and journalism as a profession more often than not now involves scraping together income as a freelancer published by different outlets rather than a regularized staff position at one media company. Precarity of employment has led to unionization efforts and labor struggles among some segments of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie, albeit ones seeking to restore lost privileged positions rather than overcome entrenched exploitation. Members of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie with established careers, either by virtue of getting hired before budget cuts and increased precarity or working in growth industries, stand in contrast, and sometimes even class antagonism, to younger and/or downwardly mobile members struggling to secure steady, high-income employment as opportunities dry up.

We should learn to take advantage of these contradictions to widen splits within the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie in order to weaken it as a class, and get some individuals within it to betray their class. But we must be sober about the fact that accomplishing the latter will require a thorough ideological rupture with the postmodernist world outlook by people who have been trained and consolidated in it. The opportunities for doing so are less in the labor struggles of downwardly mobile and early career members of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie, but more likely in political movements they join outside their occupations. In those movements, younger class aspirants without established careers are more apt to take part in actions that their career-secure class brethren will studiously avoid, as has been the case in the movement against the US-Israel genocidal war on Gaza, which we shall explore below.

Has the progressive petty-bourgeoisie gone extinct?

The growth of a new and numerically sizable reactionary petty-bourgeoisie poses strategic and tactical challenges for the proletariat and its vanguard party, especially given that the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie’s existence relies on performative involvement and practical opportunism in mass movements against real injustices. The liberal petty-bourgeoisie, by contrast, largely stays out of such movements, sometimes sympathizing with them, but other times indifferent or antagonistic towards them. It was mostly hostile to the 1992 Los Angeles Rebellion, whereas the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie swooped in on the Summer 2020 rebellions for its own opportunistic purposes. In the former scenario, the proletariat faced isolation in the face of bourgeois state repression, whereas in the latter, the proletariat faced repression with a lighter touch but also a well-orchestrated encirclement and suppression campaign in the ideological, political, and organizational domains. We believe the former to be more favorable than the latter.

The liberal petty-bourgeoisie has historically and up to the present day been most activated when it worries that bourgeois-democracy is under threat, and looks to the liberal bourgeoisie to combat the threat. When the latter fails to do so, the liberal petty-bourgeoisie may take mass political action outside the electoral arena, as it did for several months after Trump’s 2016 election, but falls back under the wing of the liberal bourgeoisie quickly (strong rhetoric and a little action from a few prominent liberal bourgeois political representatives, such as Elizabeth Warren, was all it took in early 2017).7 The rare moments when the liberal petty-bourgeoisie steps out somewhat independently, along with any sympathy it has for the struggles of the masses, should be taken advantage of by the class-conscious proletariat. At best, and unlike the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie, the liberal petty-bourgeoisie’s desire for class security under the rule of a class more powerful than itself can be used to tip sections of it over to friendly neutrality when the proletariat exerts itself on the political stage, especially during and after the conquest for proletarian state power.

Far smaller in numbers but a more reliable potential ally of the proletariat is a different ideological bloc: the progressive petty-bourgeoisie. Working in similar intellectual, cultural, and professional occupations as the liberal and postmodernist petty-bourgeoisies, the progressive petty-bourgeoisie is distinguished by its desire to stand with the masses rather than support the rule of the bourgeoisie. That makes it a firm defender of bourgeois-democratic rights and an important potential ally of the proletariat, though it does not always make it friendly towards communist ideology. At their best, members of the progressive petty-bourgeoisie have defended revolutionaries and the masses in court; produced favorable journalistic coverage of the masses and their struggles; created art that displays heart for the masses, contempt for the present system, and optimism for the future; and carried out intellectual work that provides exposure and analysis of the current system and raises thoughtful questions about the struggle to get beyond it.

One troubling effect of the rise of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie is that it has made the progressive petty-bourgeoisie go virtually extinct as a class. On an institutional level, the former has been taking the place of the latter. For example, the National Lawyers Guild, a creation of the communist-led Popular Front movement of the late 1930s and formerly the preserve of the progressive petty-bourgeoisie, has been taken over by the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie, as evident by the fact that the Guild appointed a white woman as its first Latina president.8 Embarrassing virtue signaling aside, the National Lawyers Guild has went from an organization of lawyers with some fight in them to a performative part of protest culture, encouraging plea deals rather than treating the courtroom as an arena of struggle. Other examples of postmodernist capture or supplanting of progressive petty-bourgeois class positions include academic departments at universities, especially in Black Studies and Women’s Studies, arts institutions, and independent journalism and bookstores.

Losing institutional clout, remaining members of the progressive petty-bourgeoisie have become lone voices in the wilderness, sometimes speaking out against the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie’s self-serving behavior and failure to defend bourgeois-democratic principles, but largely left out of “the discourse” or even disciplined and punished for voicing dissent. Some gave up and joined the postmodernists, while others have went silently into submission. Remaining progressive petty-bourgeois stalwarts are aging out of existence, as symbolized by Noam Chomsky recently losing the ability to speak and write. The last additions to the progressive petty-bourgeoisie, who came of age twenty years ago, must become mavericks to stick to their principles, as symbolized by Vincent Bevins—a John Reed without a Bolshevik Revolution—living outside the US while writing a book about recent resistance movements that bucks the trend of asinine optimism and collective celebratory self-congratulation.9

With respect to the progressive petty-bourgeoisie, communist cadre and class-conscious proletarians must play a role analogous to the scientists of Jurassic Park, rescuing its DNA from the amber and resurrecting it as a class. Doing so has great strategic import—we need lawyers, journalists, artists, and professional intellectuals in our corner, including to defeat repression—and will create a counterweight necessary for rolling back the reactionary advance of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie.

The revanchist petty-bourgeoisie and the Trumpist coalition

Whereas the reactionary nature of the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie is obfuscated by its self-presentation and participation in mass movements against real injustices, the revanchist petty-bourgeoisie is open about its hostility towards the masses and more obviously a class enemy of the proletariat. Therefore, we will spend less time exposing its reactionary nature and more time explaining how and why, as an ideological bloc, it burst onto the political stage immediately after the 2008 election of Obama to the presidency, embraced wrecking as a political strategy, paved the way for Trump’s first presidency, and has remained an assertive force pushing US politics in a reactionary direction.

When (finance) capital runs amok and causes crisis, as in the 2008 collapse of the housing market, bourgeois government’s job is to clean up the mess and restore order to the process of capital accumulation. Doing so requires propping up failing blocs of capital integral to bourgeois class power (big banks, for example), imposing government regulation to rein in the anarchic motions of capital, and appeasing the masses and sections of the petty-bourgeoisie who face economic ruin and/or downward class mobility with state-funded economic rescue so that they do not break out in rebellion. The Obama administration did the first, some of the second, and virtually none of the third. Consequently, some classes in society, already confronting the dislocating effects of the reconfiguration of capitalism-imperialism over the previous three decades, perceived the 2008 crisis and the Obama administration’s response to it as posing existential threats to their class interests. Chief among them were sections of the petty-bourgeoisie, mostly white, concentrated as small business owners, as well as skilled-labor professionals adjacent to them, in (outer-ring) suburbs and exurbs, towns, small cities, and rural-ish parts of the country, outside the large cosmopolitan cities that the postmodernist petty-bourgeoisie favors. They were arguably among the least affected by the crisis but had more to potentially lose as home owners and petty proprietors, especially as they entered retirement and expected to be able to enjoy their privileged class position. In defense of their entrenched class interests, they constituted themselves as an ideological bloc: the revanchist petty-bourgeoisie.

That ideological bloc exerted itself onto the political stage as the Tea Party movement beginning in 2009, Obama’s first year in office. The social base of the Tea Party was not principally the white working class, a term often used in reductionist and analytically unproductive ways. As Theda Skopcol and Vanessa Williamson document, Tea Party participants were overwhelming, though not exclusively, white, but occupationally, “the plurality seemed to be small business owners in fields like construction, remolding, or repair.” In their entrepreneurial activities, they interacted little with the proletariat as employees or as customers, instead serving and working with people in social positions similar to themselves. In other words, they were fairly segregated from people not like them, and worked in small-scale private enterprise, with few public-sector employees among them. Besides its occupational proclivity and nationality, the other distinguishing demographic characteristic of Tea Partiers was their age: mostly over 45 years old, with many retirees among them, and few under 45. This was not an aspiring section of the petty-bourgeoisie, but one that had secured its position over the course of decades and sought to keep it that way into retirement.10

In the Obama administration, Tea Partiers saw a dire threat to their class interests. In their eyes, government bailouts of the banks portended coming handouts to sections of the population they deemed unworthy of government assistance—Black proletarians, immigrants, public-sector employees, lazy young people, and all those who, unlike themselves, had failed to secure employment or entrepreneurial success. Worse yet, the taxes they had spent their whole lives paying—on their hard-earned income, no less—would be footing the bill, and potentially bankrupting the government benefits they expected to be able to rely on in retirement, such as Social Security and Medicare. As its name suggests, the Tea Party was a movement of the reactionary taxpayer. To Tea Partiers, their taxes being spent on “freeloaders” rather than funding their idyllic retirement was the last chapter in the long saga of government regulation run amok they had been contending with throughout their careers. As petty proprietors, they had spent their whole adult lives up against “intrusive bureaucrats” enforcing “irritating business regulations or local zoning rules,” and the Obama administration was just a larger, more intrusive version of the same.11 The Affordable Care Act—so-called “Obamacare”—earned the ire of Tea Partiers more than any other government policy exactly because, from their worldview, it concentrated everything they considered a threat to their class interests: their taxes used to fund social welfare for lazy, undeserving freeloaders in a program overseen by intrusive government bureaucrats and regulatory agencies who were now going to dictate which doctors you see.

In President Obama himself, the Tea Party found the symbolic target of their petty-bourgeois rebellion, in a way analogous to how the proletariat, Black people, and the progressive petty-bourgeoisie had found in Ronald Reagan the symbol of everything they hated in the 1980s. For starters, Obama is Black, and the Tea Party movement was steeped in racism, albeit usually expressed as a persistent undertone without uttering the N word. Beyond his nationality, however, Obama’s path to the presidency symbolized two classes the revanchist petty-bourgeoisie hates with indignant passion. As a “community organizer” (yes, we know not to take that label seriously, but the the revanchist petty-bourgeoisie does not), Obama had ostensibly served the urban, mostly Black, proletariat. As a Harvard Law School graduate and subsequently a law school professor, Obama was part of the coastal liberal elite (in our terminology, the upper echelons of the liberal petty-bourgeoisie).12

The revanchist petty-bourgeoisie at the head of the Tea Party had generally spent their whole lives as a social base for the conservative side of the bourgeoisie, some having been involved in the 1964 Barry Goldwater presidential campaign, and the politics of the Tea Party draw on a longer inculcation, via right-wing media, in opposition to “big government” and animosity towards the masses.13 But the rabidly revanchist turn after 2008 was a response to the specific historical conjuncture and the product of conscious ideological work. Libertarianism, boosted by the 2008 Ron Paul presidential campaign, was part of the mix, as was virulent anti-immigrant sentiment. While they readily identified the Muslim world as an external and internal enemy to their country, Tea Partiers were not gunning for military intervention. The Bush years had soured them from imperialist adventurism, and from the mainstream of the Republican Party. Moreover, as a class, the revanchist petty-bourgeoisie operates economically in the home market, not directly profiting from imperialist exploitation even as its privileged class position rests on that exploitation. It embraces American patriotism and its members often proudly serve in the military, but it views its class interest rather narrowly and consequently fails to grasp how foreign wars will advance those class interests absent being won over to perceive an external enemy that poses a direct threat to its way of life.

The crankish outer appearance of the Tea Party movement, especially when its activists dressed up in colonial garb, can obfuscate the fact that through it, the reactionary initiative of the revanchist petty-bourgeoisie succeeded in constituting a politically mobilized ideological bloc that had wide-reaching, transformative impact on government personnel and functioning. As a voting bloc, the Tea Party movement likely soared to a fifth of voting age adults (46 million people), and at the core of that voting bloc were thousands of dedicated activists (including many retirees with plenty of free time) and tens of thousands of active participants.14 In an early example of “how boomers beat millenials at the internet,”15 Tea Partiers proved adept at using Facebook and internet mobilizing tools pioneered by MoveOn.org (to organize the liberal petty-bourgeoisie). Through a loose network of local organizations, the Tea Party movement created a politically engaged crowd that was willing to protest, campaign, and, most importantly, hold elected officials accountable. Tea Partiers studied how government functions, inserted themselves into the functioning of the Republican Party, unseated Republican incumbents in favor of their preferred candidates, and tracked legislation to ensure that their revanchist politics advanced in Congress and punished those that blocked their advance.16

On the basis of its political and organizational work, together with the support of Fox News and a few billionaires (more on this below), the Tea Party movement scored impressive victories in the 2010 election, with its preferred candidates constituting a bloc in Congress, and captured positions in state legislatures and a few governorships. Once in office, Tea Party-aligned politicians proceeded with a slash, burn, and block approach, seeking to cut social welfare and government regulation, along with the taxes that funded them. When they could not get their way, they preferred to prevent normal government functioning than compromise their position, with fights over the federal budget causing, or nearly causing, government shutdowns (with the Tea Party’s much hated public-sector employees being left without paychecks). Beyond specific legislative goals, the toddler-like, tantrum-laden behavior of the revanchist petty-bourgeoisie and its political representatives cemented a strategy of wrecking as a means to defeat opponents, including those belonging to the traditional Republican Party establishment, and celebrated the art of disruption. In this respect, the revanchist petty-bourgeoisie proved its power as a class to reshape the political landscape and bend government to its will. Indeed, efforts by the Reaganite Republican Party establishment to rein in this reactionary social base resulted in failure, from the rejection of Newt Gingrich’s restorationist attempt to bring back the 1990s, to the 2012 Mitt Romney campaign’s failure to inspire, to the incumbents unseated by Tea Party-aligned challengers.17 Since 2010, the revanchist petty-bourgeoisie has displayed a relentless and increasingly reactionary drive to champion its class interests inside and outside the halls of power, undaunted by setbacks and refusing to play fair or respect the established rules of bourgeois government and decorum. Given their attitude and efficacy, it is no surprise that they looked to Donald Trump as their champion.