By Kenny Lake

At the end of World War II, the writing was on the wall. “High colonialism,” the form through which the European imperialist powers had divided up Africa and Asia into colonies under their direct control, was coming to an end. The European powers that had carved up the world into colonies during the nineteenth century no longer possessed the military might, political power, or economic ability to hold on to their colonies. Ironically, it was the world war they fought with each other for the redivision of those colonies that had wrecked their ability to hold on to the very colonies they were fighting over.

Whatever hopes the European imperialist powers had for regaining their strength were dashed by three factors. (1) The oppressed masses in the colonies were rising in revolt, seeking to throw off the yoke of colonial rule and establish independence, i.e., political sovereignty over their territory. (2) A sizable socialist camp emerged after WWII, with the Soviet Union joined by several Eastern European countries and then China. The socialist camp acted as a bulwark against imperialist domination and directly supported anticolonial revolt. (2) A new imperialist power, the United States, supplanted Britain at the top of the imperialist order, and by and large chose, in the face of factors one and two, to implement new forms of foreign domination which it had workshopped in Latin America over the previous century. Consequently, high colonialism came crashing down, but the division in the world between imperialist powers and oppressed nations continued in postcolonial forms of imperialism.

The decolonization process that brought down high colonialism had a wide variety of results and proceeded along different paths depending on the forces fighting to cast off colonialism and the degree to which the European powers tried to cling on to their colonies. Where decolonization was led by genuine communists, with Maoist China as the preeminent example, it was a thoroughgoing revolution against not just the colonial (or semicolonial) form of rule, but the entire production and social relations on which capitalist-imperialist domination rested. Where it was led by forces with the outlook of the national bourgeoisie, newly independent former colonies sought development on a capitalist basis, and wound up back under imperialist domination in a new form. A more complex picture of this process will be given in part two.

As for the European powers’ role in (resisting) the decolonization process, Britain was more willing than others to relinquish its colonies because its close alliance with the US ensured it favored status in the new imperialist arrangement. France employed the British “polite” exit in some places, but also fought brutal wars to keep its colonial control over Algeria and Vietnam. Portugal, which had gotten an early start at global domination only to see its position decline to that of third-rate imperialist well before the twentieth century, clung on most desperately to its colonial positions with all the bloody consequences for its colonial subjects in Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, and Angola. In southern Africa, where the fusion of high colonialism with settler-colonialism created a sizable and reactionary social base for clinging on to the old order, apartheid states in Zimbabwe and South Africa lasted into the late twentieth century. But regardless of the resistance put up by the overlords of high colonialism, and whatever the path that newly independent former colonies took, the old colonial order was set on the path to extinction after WWII.

Since the old colonial forms were jettisoned because, in most cases, they no longer best served capital accumulation by the dominant imperialist power(s) rather than due to any matter of moral principle, they stayed in stock but not on the display case, used under updated labels when demanded by the situation. A few relatively small number of “overseas territories,” such as Puerto Rico, remained colonies, formally denied sovereignty and officially dominated over by an imperialist power. And in one instance, imperialism took the old forms off the shelf, dusted them off, and repackaged them. Such was the birth of Israel.

Israel was, and is, imperialism’s necessary aberration in a postcolonial world. Without direct colonial control, the imperialist powers needed to develop new forms to ensure that capital accumulation—the economic logic of capitalism-imperialism—continues, and continues in the direction of the imperialist powers. In the Arabian Peninsula, imperialism could leave nothing to chance. Strategically positioned as a point of passage for world trade routes going back centuries, stability in the region is crucial to ensure the steady flow of goods that is necessary for capital accumulation. The Suez Canal is today one of the most important passageways for the ships that literally produce the aforementioned flow of goods. If being one of the centers of world trade routes was not enough to merit imperialism’s special attention, the Arabian Peninsula is also pivotal for another reason: oil. Below the sands sits the largest load of the liquid lifeblood of capitalist production, which the imperialist powers must have access to in order to maintain their position.

So when Britain and France gave up their “mandates,” i.e., colonies, in the Arabian Peninsula, capitalism-imperialism had to ensure continued access to the oil beneath the surface and the seaways around it. Part of the uneasy solution was welcoming a new bourgeois class—oil rentiers—as subaltern beneficiaries of capital accumulation. In the case of Saudi Arabia, that meant propping up a monarchy as an oil rentier bourgeoisie. Other regimes in the region, with their own bourgeois nationalist inclinations, provoked the anxiety of the old European powers and the newer American one, and not without (imperialist) reason, as subsequent events would show. Nasser’s nationalist government in Egypt nationalized the Suez Canal Company in 1956, an act of defiance that was met with military attack by Israel, Britain, and France. And in 1973, Arab oil rentier bourgeoisies, via OPEC (the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries), enacted an embargo on oil sales to countries that supported Israel during its war on neighboring countries, resulting in a dramatic rise in the price of oil that hurt capital accumulation for the imperialist powers.

Beyond the economic and political causes, imperialist anxiety also had a more longstanding ideological source. Calling attention to the way the Arabian Peninsula and its environs was constructed as the Orient in the European imperialist world outlook, Edward Said explained that

[t]he Orient is not only adjacent to Europe; it is also the place of Europe’s greatest and richest and oldest colonies, the source of its civilizations and languages, its cultural contestant, and one of its deepest and most recurring images of the Other. In addition, the Orient has helped to define Europe (or the West) as its contrasting image, idea, personality, experience.1

With those historical and contemporary anxieties in mind after WWII, imperialism’s insurance policy for ensuring its dominance in the Arabian Peninsula in a postcolonial world was the creation of Israel as a beachhead of Western imperialism to keep unreliable allies in check and as a rapid-response strike force to be deployed against adversaries when necessary (as the 1956 Egypt example above highlights). To create Israel, the imperialists welcomed old colonial methods: seizing territory, expanding territorial dominion through the deployment of settlers, dispossessing the Indigenous population, and expelling much of the Indigenous population from its land and subjecting those who remained to occupation and apartheid. To ensure Israel’s survival, imperialism outfitted it with the most advanced weaponry and technology, thereby combining the most modern tools of vicious violence with the old forms of foreign domination. Conveniently, Israel also provided a reactionary resolution to the Jewish question in Europe, ending centuries of official European antisemitism and successions of pogroms that led up the Nazis’ genocide of six million Jews by installing Jewish settlers, backed up by US and European imperialism, as oppressors and exterminators of Palestinians.

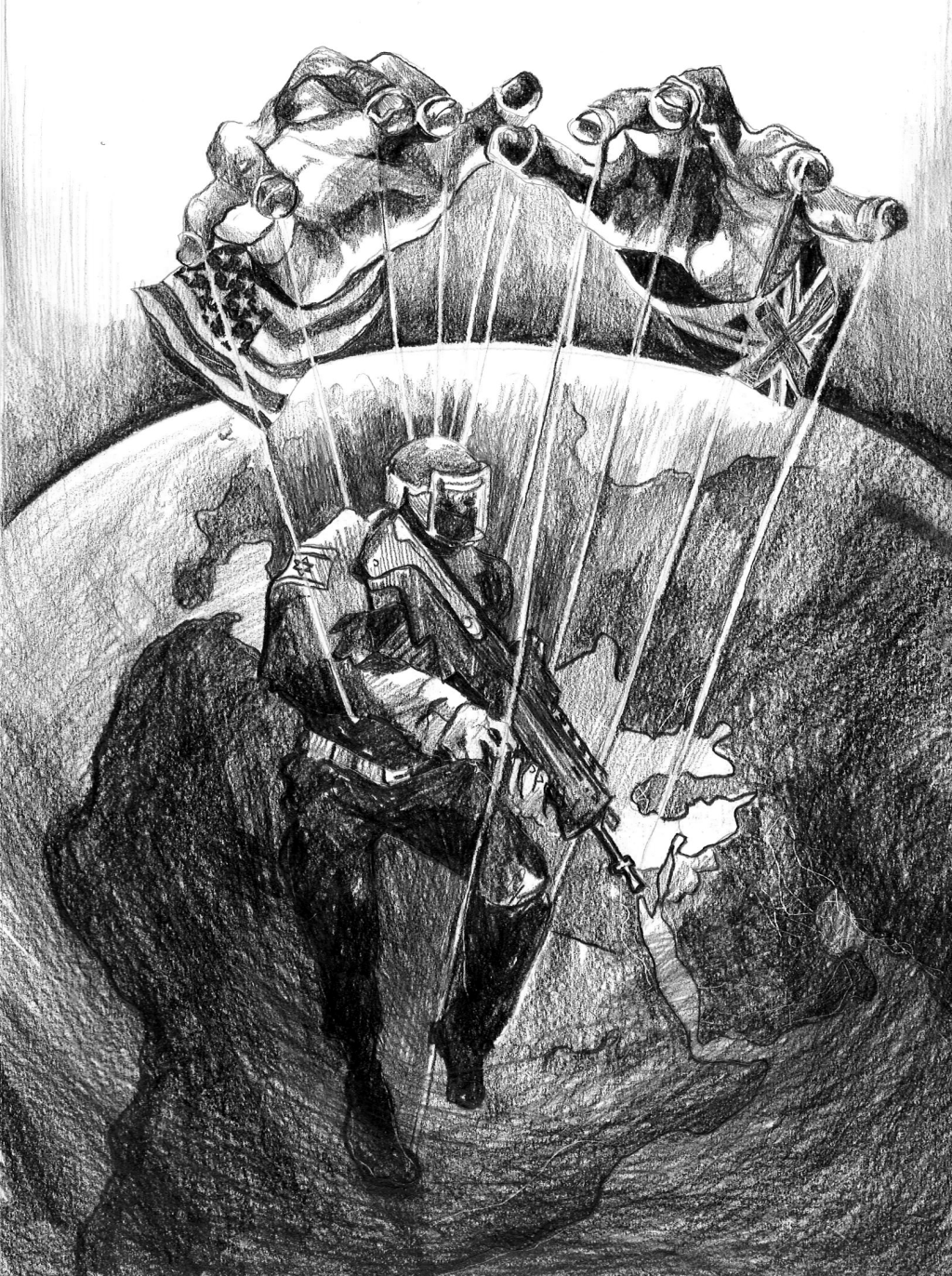

Israel has served imperialism well, waging war against its neighbors when they got out of line and carrying out sabotage and assassinations against governments and political forces who do not fit into the established imperialist order, all while demonstrating imperialism’s willingness to clamp down on genuine national liberation struggle. Israel also proves that imperialism is not invincible, as the Palestinian people have refused to give in, bravely resisting the most well-armed occupying force in human history. Furthermore, the role of Israel demonstrates that the imperialist powers are not merely puppeteers, but must rely on a number of junior partners who have their own interests, which overlap with but are not identical to those of the larger imperialist powers. In the case of Israel, its foundation on, and continued use of, the old forms of territorial- and settler-colonialism mean that it frequently pushes further in brutality than what the US bourgeoisie would prefer (due to that brutality’s potential to provoke destabilization in the region, not any moral concern), but without consequence because it is so necessary for the imperialist order. As US imperialism’s domination over the Arabian Peninsula has been weakened over the last couple decades, Israel has turned up the dial on brutality as part of an attempt to maintain (US) imperialist hegemony in the region—hence stepped-up settler incursions in the West Bank and the war on Gaza beginning in October 2023, in which hospitals, mosques and churches, refugee camps, and journalists have all been targets of bombings.

Understanding Israel’s role in the world imperialist system forces us to acknowledge that while the bourgeoisie, as a class, is driven by capital accumulation, it must also think strategically about how to best maintain the conditions for continued capital accumulation. That is why the bourgeoisie has governments and armed forces. Bourgeois state power exists not to narrowly serve the profit motives of this or that member of the bourgeois class, but to serve the class interests of the bourgeoisie as a whole. In the case of Israel, ensuring the conditions, in the Arabian Peninsula region, for continued capital accumulation by the dominant imperialist power(s) required employing methods and forms associated with settler-colonialism and high colonialism on land that rightfully belongs to Palestinians, and Palestinians have been denied national sovereignty as a result. The main motive for maintaining Israel is not its exploitation of Palestinian labor or potential oil on Palestinian land, although both are part of the picture, but the imperialist bourgeoisie’s larger geostrategic concerns in the region—how to maintain the optimal conditions for capital accumulation.

Israel’s brutal subjugation of Palestine is a case of colonialism in the present, and anywhere in the world where colonialism as a form of rule still exists, the struggle for political sovereignty over territory—the anticolonial struggle—remains on the agenda. But in most of the world, the forms of domination that best serve the imperialist bourgeoisie are not colonialism. The division of the world between imperialist powers and oppressed nations now mostly takes the form of formal sovereignty for the oppressed nations, who are saddled with debt, subjected to economic domination in the form of free trade regimes, turned into zones of industrial and agricultural production and resource extraction for the benefit of foreign imperialism, and/or cast aside from the global capital accumulation process and left to rot when their lands and people cannot be profitably exploited, with these conditions enforced by the US military bases that dot the planet and the US warships that stalk the seas. The division of the world between imperialist powers and oppressed nations itself has become more complex in recent decades, with various subaltern nations propped up by, but still subordinate to, the imperialist powers and new imperialist powers rising and seeking to challenge the existing US hegemony. Mostly missing from the mix (or mess) today are the forces—communist revolutionaries and class-conscious, revolutionary masses—that can overturn this whole order and begin the socialist transition to communism.

One reason for this absence is that many who want, or claim to want, to overturn the existing order are either fighting ghosts or chasing fantasies. Over the last decade, the Left, certainly in the US but also in many other parts of the world, under the influence of (or intoxicated by) postmodernism, has chosen to analyze contemporary reality through the prism of colonialism, a form that, with some important exceptions, has vanished from the landscape. While busy fighting the ghosts—albeit ghosts that constitute a dead weight of the past on the present—of settlers and colonialism, they fail to rise to the challenge of overthrowing the contemporary monsters of capitalism-imperialism. Simultaneously, some who have the intelligence to know better and others who do not have decided to place their hopes on an imagined path of development outside the dictates of US imperialism but still beholden to the logic of capital accumulation, with the supposedly now multipolar world creating the dreamscape for this fantasy. Whether fighting ghosts or chasing fantasies, the common thread is capitulation, in this case by refusing to confront contemporary reality as it is in order to evade the reality that making revolution entails.

Capitulation is an ideological question, but perhaps we can remove the obfuscation that surrounds it if we get rid of the ghosts and fumigate the fog of fantasy through an analysis of the past and present of capitalism-imperialism. The aim of such an analysis is to demonstrate that through different forms and historical processes, the logic of capital accumulation has been the driving force that brought us the monstrosities of colonial brutality and present-day postcolonial imperialist domination. That is not to say there are not other logics at play as well, and so we must show how those logics relate to the central logic of capital accumulation. The conclusion we are working towards is that if we want an end to these monstrosities, we must end the logic of capital accumulation, not fixate on the previous forms it took or look for a more friendly form of it.

Our priority, if we are serious about revolution, must be understanding the present conditions of capital accumulation that we must overthrow. But knowing how we got here, and how those conditions differ from the ones that previous generations of revolutionaries confronted, requires some understanding of the prior conditions of capital accumulation. To that end, we will have to go back to around 1500 when the logic of capital accumulation started to become a dominant force in the world and at least summarize the forms that logic created up until the present. Along the way, we are obliged to take stock of, and try to remedy, secondary weaknesses in Marxism that might hinder our understanding of how the logic of capital accumulation has shaped world history for the last five centuries. By contrast, the postmodernist idiocy and neodevelopmentalist fantasy that serve to justify capitulation need nothing less than rebuke and ridicule.

What follows is mainly the story of the bourgeoisie, not the masses whose lives it has and continues to ruin, nor of the masses—the same masses—who have risen up in revolt against bourgeois rule, and sometimes won. The latter is the story we wish to write the next chapters of but can only do so by way of knowing our enemy well. The purpose of this writing is not to prove the bankruptcy of bourgeois rule—I assume if you are reading this, you have already drawn that conclusion—so it will not dwell on exposing the monstrous crimes of capitalism-imperialism, as much as it is important to expose those crimes. The history presented will largely be an outline that leaves out much in favor of examples that best serve to bring us to the theoretical abstraction necessary to understand how the logic of capital accumulation has operated over the last five centuries. The interested reader is encouraged to dig deeper into the concrete history surrounding capital accumulation with further study. We are concerned here with addressing the more contentious questions of analysis and ideological outlook when it comes to understanding capitalism-imperialism and how to overthrow it.

* * *

In what follows, while sources of specific information and ideas are cited in footnotes, where the factual information is common historical knowledge or where the historical narrative is a synthesis of a variety of sources, no citation is provided. Theoretical work and historical analysis by Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, Mao, and other communist leaders looms large in my own synthesis of the history of capitalism-imperialism, but I usually only cite their work when needed to deal closely with a specific point of contention. The writings of Giovanni Arrighi, Eduardo Galeano, Walter Rodney, and Ellen Meiskins Wood are drawn on heavily in the historical narrative that follows, which, more than anything, is an attempt to synthesize, and recast from a communist perspective, the insights of others rather than invent a wholly original historical narrative. Originality in the individual sense is, after all, a prized value of the petty-bourgeoisie, not the guiding intellectual principle of the proletariat in its collective mission to overthrow the bourgeoisie and lead humanity to communism.

1Edward Said, Orientalism (Vintage Books, 1979), 1–2. While this quote from the book’s opening pages brilliantly encapsulates one of Said’s central arguments, please do not follow the postmodernist graduate student practice of only reading the introduction of Orientalism—Said deserves much more from us intellectually than that.